Why Vietnam’s Sudden 1,333-Acre Surge Changes the Rules of War

The new Gunboat Diplomacy isn’t just ships; it’s creating land to base them on

For decades, the concept of “Gunboat Diplomacy” was simple: if you wanted to project power or coerce a neighbor, you sent a fleet. The ships would arrive, loom offshore, and eventually leave. But in 2024, the South China Sea witnessed the maturation of a far more permanent strategy. The ships aren’t just visiting anymore; they are building the ground they wish to anchor on. While the world has long focused on China’s massive artificial islands, a new data-driven reality has emerged: Vietnam has quietly but rapidly begun to match the scale of Beijing’s construction, fundamentally altering the region’s strategic calculus.

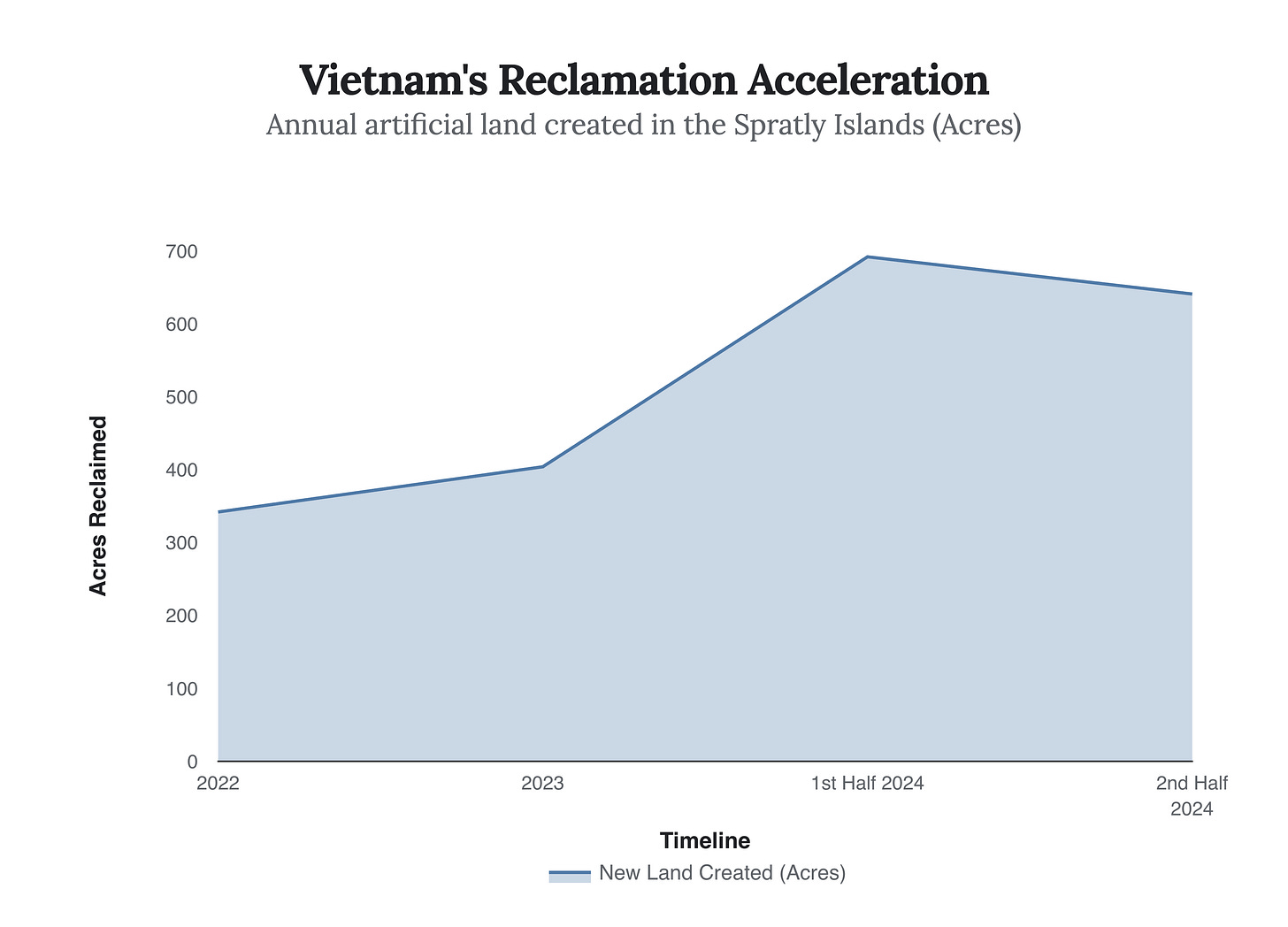

The latest satellite data reveals a stunning acceleration. In a single year—2024—Vietnam created approximately 1,333 acres of new land in the Spratly Islands. To put this figure in perspective, that is more land created in twelve months than in the previous two years combined. This is not merely coastal erosion control; it is the wholesale manufacturing of sovereignty. The ocean floor is being dredged, pulverized, and piled up to create runways, harbors, and radar stations where only coral reefs once existed. The result is a shift from transient naval power to permanent, unsinkable “gunboats” made of sand and concrete.

The chart above illustrates the dramatic “hockey stick” growth in Vietnam’s dredging operations. After years of modest improvements, Hanoi initiated a breakneck expansion campaign in late 2023 that continued through 2024. This surge is not accidental. It is a calculated response to the militarization of the region, ensuring that Vietnam’s claims are backed not just by historical maps, but by physical reality. These new acres are being paved immediately—often for military logistics.

“Vietnam is still surprising observers with the ever-increasing scope of its dredging and landfill... creating harbors that allow for longer patrols and permanent presence.”

The strategic logic here is “standing reserve.” A ship must return to port to refuel; an island base does not. By constructing large artificial features, nations can forward-deploy coast guard vessels, missile batteries, and surveillance radar deep into disputed waters. The logistical advantage is immense. China demonstrated this first with its “Big Three” reefs (Subi, Mischief, and Fiery Cross), effectively extending its operational range by hundreds of miles. Now, Vietnam is playing the same game, but with a different strategy: while China built a few massive fortresses, Vietnam is expanding a vast network of smaller outposts.

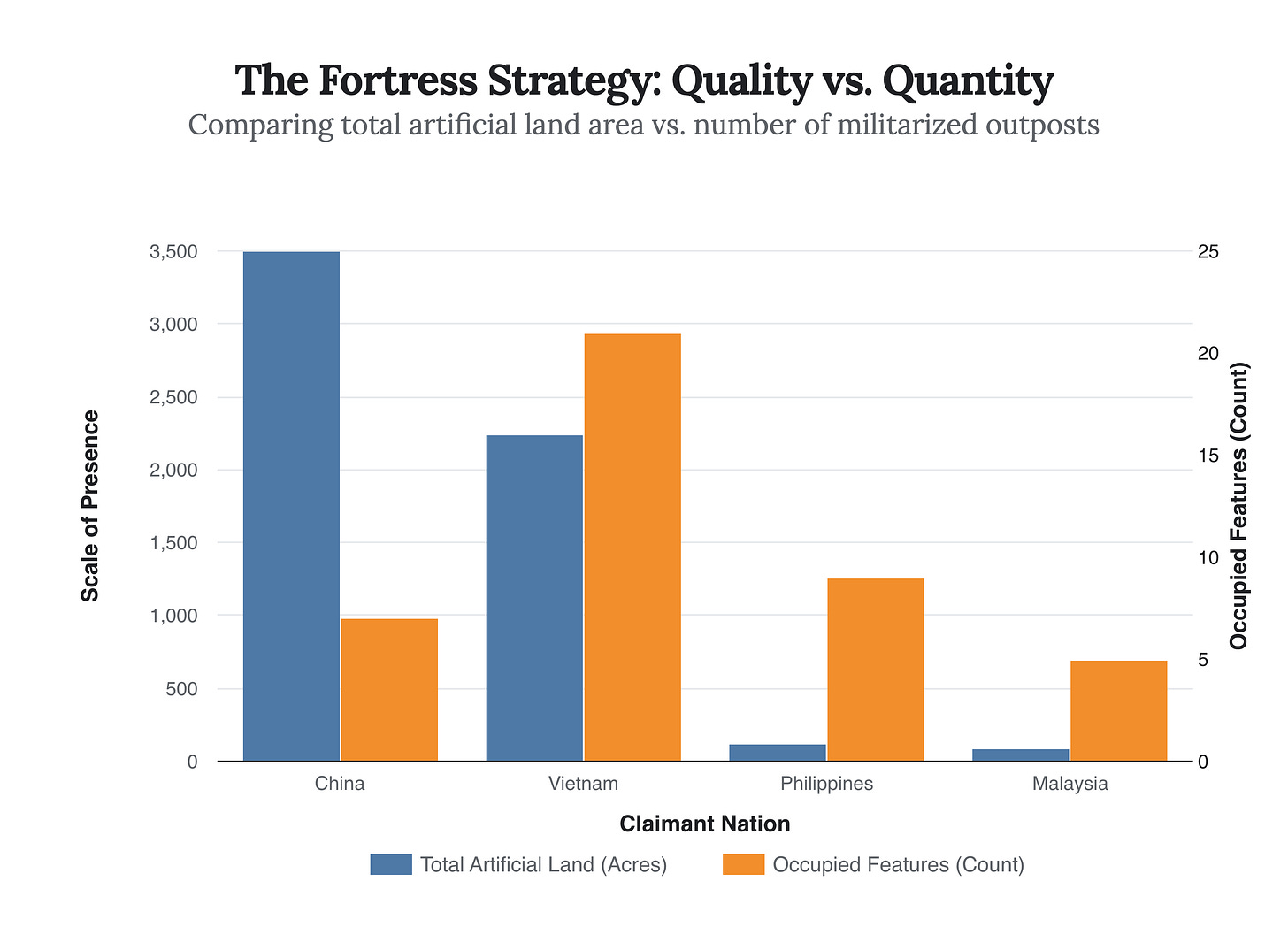

As the comparison above shows, the disparity between the two primary builders is shrinking. While China still dominates in total acreage (approx. 3,500 acres), Vietnam has now reached nearly 64% of that total, a figure that would have seemed impossible just five years ago. More importantly, Vietnam’s “Archipelago Strategy” spreads this risk across 21 different features, compared to China’s 7. This distribution makes the Vietnamese network harder to neutralize in a hypothetical conflict, creating a “porcupine” defense of hardened, scattered points.

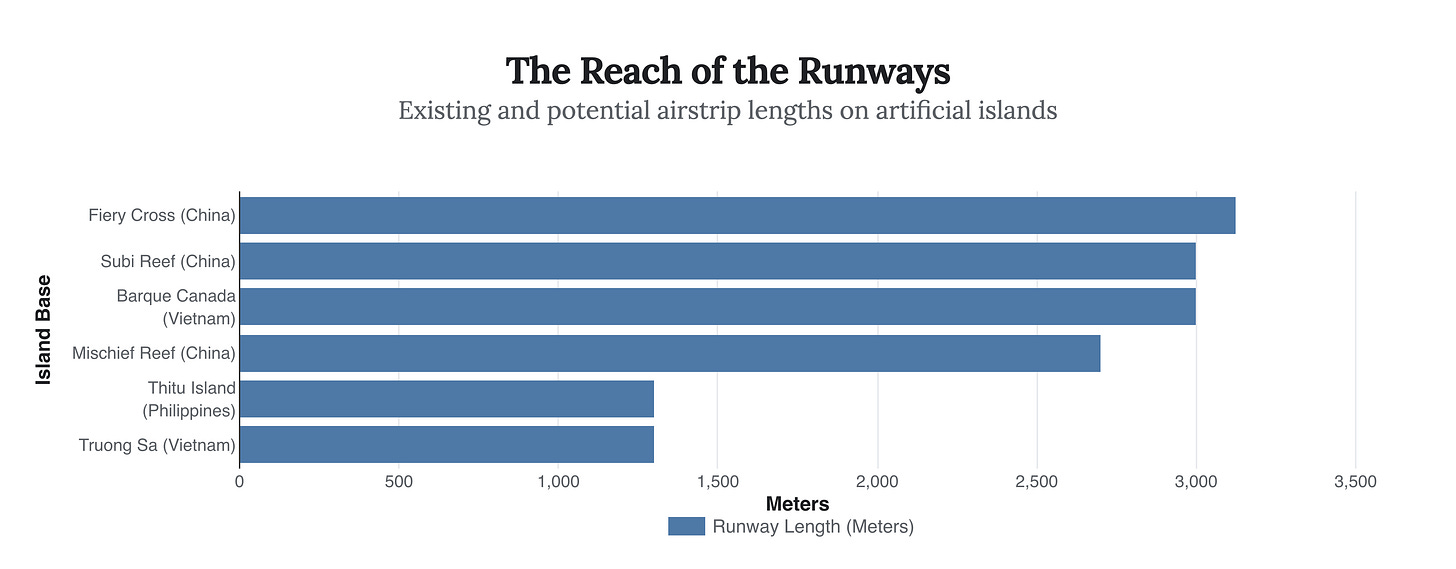

The implications of this “New Gunboat Diplomacy” extend beyond mere acreage. The type of infrastructure being built suggests high-intensity capabilities. Recent satellite imagery of Barque Canada Reef—one of Vietnam’s largest new expansions—shows land preparations conducive to a 3,000-meter runway. Such a strip would be capable of handling heavy military transport aircraft and combat jets, rivaling the capabilities of China’s Fiery Cross Reef. We are witnessing an arms race where the “arms” are literally the islands themselves.

“The ships aren’t just visiting anymore; they are creating the ground they wish to anchor on.”

This construction boom also serves a diplomatic function: it makes reversal impossible. It is one thing to demand a fleet leave your waters; it is another to demand a nation remove a 600-acre island made of millions of tons of sand and concrete. These features harden the status quo. They transform international waters into de facto territorial seas through the sheer weight of infrastructure.

The race to 3,000 meters is critical. A runway of that length allows for the deployment of strategic assets—heavy bombers, large surveillance aircraft, and long-range logistics haulers—rather than just short-range fighters. If Vietnam completes a 3,000-meter strip at Barque Canada Reef, it will effectively checkmate China’s monopoly on heavy airpower in the southern Spratlys.

In conclusion, the era of transient naval power in the South China Sea is ending. It is being replaced by a static, high-stakes game of geo-engineering. The new Gunboat Diplomacy is not about showing the flag; it is about planting it in concrete. By creating over 1,300 acres of new land in a single year, Vietnam has demonstrated that in the modern era, the most powerful weapon is not a missile, but a dredger.