Why the “Stealing Option” Was Ditched for a $50 Billion Loophole

Inside the high-stakes financial alchemy turning frozen Russian assets into a war chest

It is perhaps the most ironic financing structure in the history of modern warfare: Russia’s own sovereign wealth is now underwriting the very weapons destroying its tanks on the Ukrainian front. But behind the headline figure of the newly finalized $50 billion G7 loan lies a fierce, year-long battle over what insiders call the “stealing option”—the full confiscation of frozen assets.

For months, Washington pushed Brussels to simply seize the roughly €260 billion in Russian Central Bank assets immobilized across the West. It was the ultimate “stealing option”: quick, punitive, and morally satisfying to Kyiv’s allies. Yet, the European Union blinked. Fearful of destabilizing the Euro and provoking a global sell-off of European assets, the EU pivoted to a complex legal workaround that leaves the principal untouched while harvesting the “windfall profits” to service a massive loan.

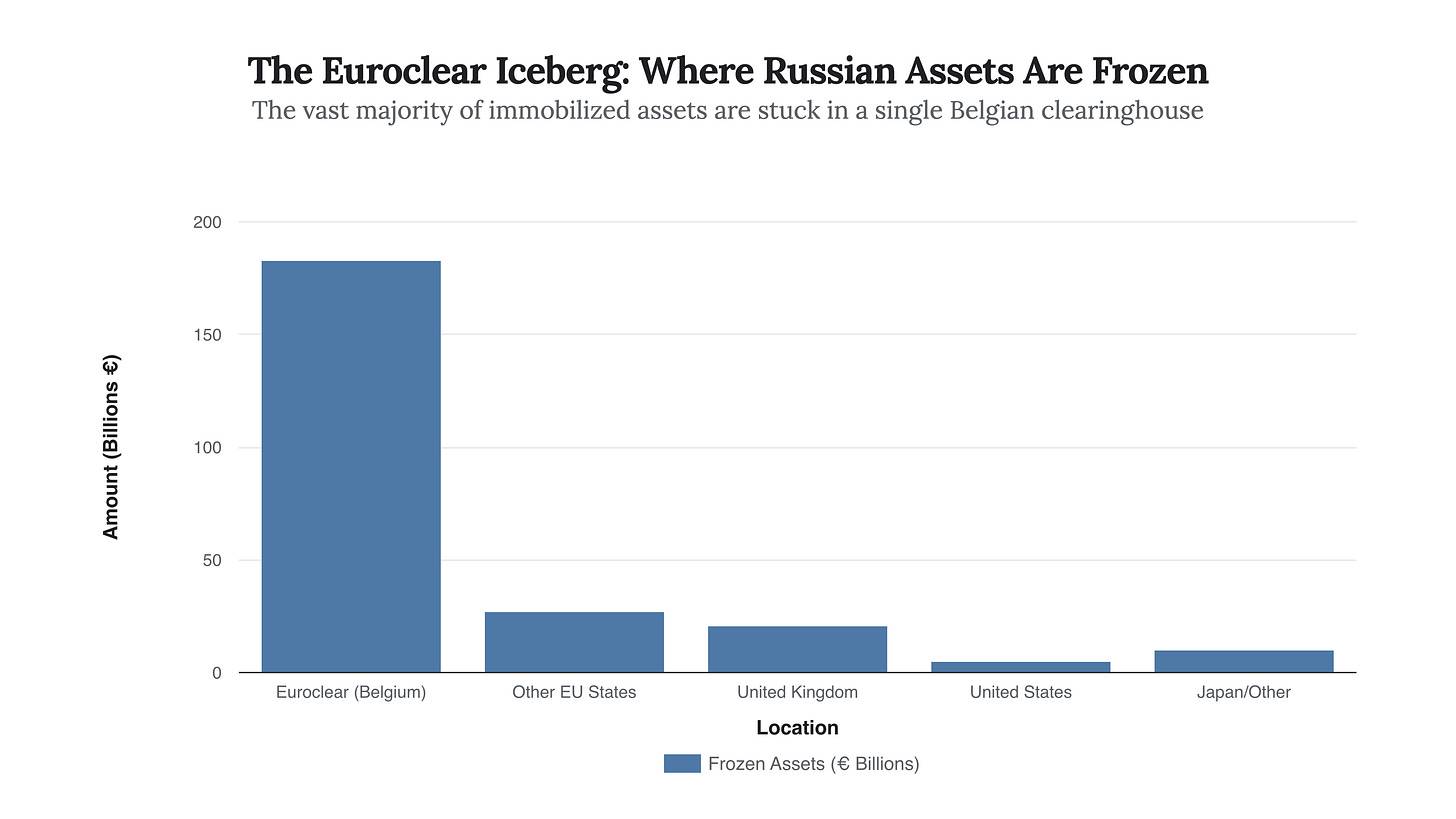

This decision has created a financial anomaly: a €210 billion pile of cash that sits in a Belgian vault, legally belonging to Russia, yet working overtime for Ukraine. To understand why the West chose this path, we must look at the sheer scale of the assets trapped in the EU’s financial plumbing.

The chart above reveals the geopolitical asymmetry that killed the “stealing option.” While the political pressure to confiscate assets often originated in Washington, the United States holds a negligible slice of the pie—only about $5 billion. The overwhelming burden rests on the European Union, specifically within Euroclear, a systemically important clearinghouse in Belgium holding €183 billion of the immobilized funds.

The legal argument against confiscation was stark. European Central Bank officials warned that seizing the principal would signal to other nations—like China or Saudi Arabia—that their Euro-denominated reserves were not safe, potentially undermining the currency’s status as a global reserve. As one EU diplomat privately noted during the negotiations:

“You can ring-fence the assets, but you cannot ring-fence the reputation of your currency. If we cross the Rubicon of confiscation, we may find no one left on the other bank willing to buy our debt.”

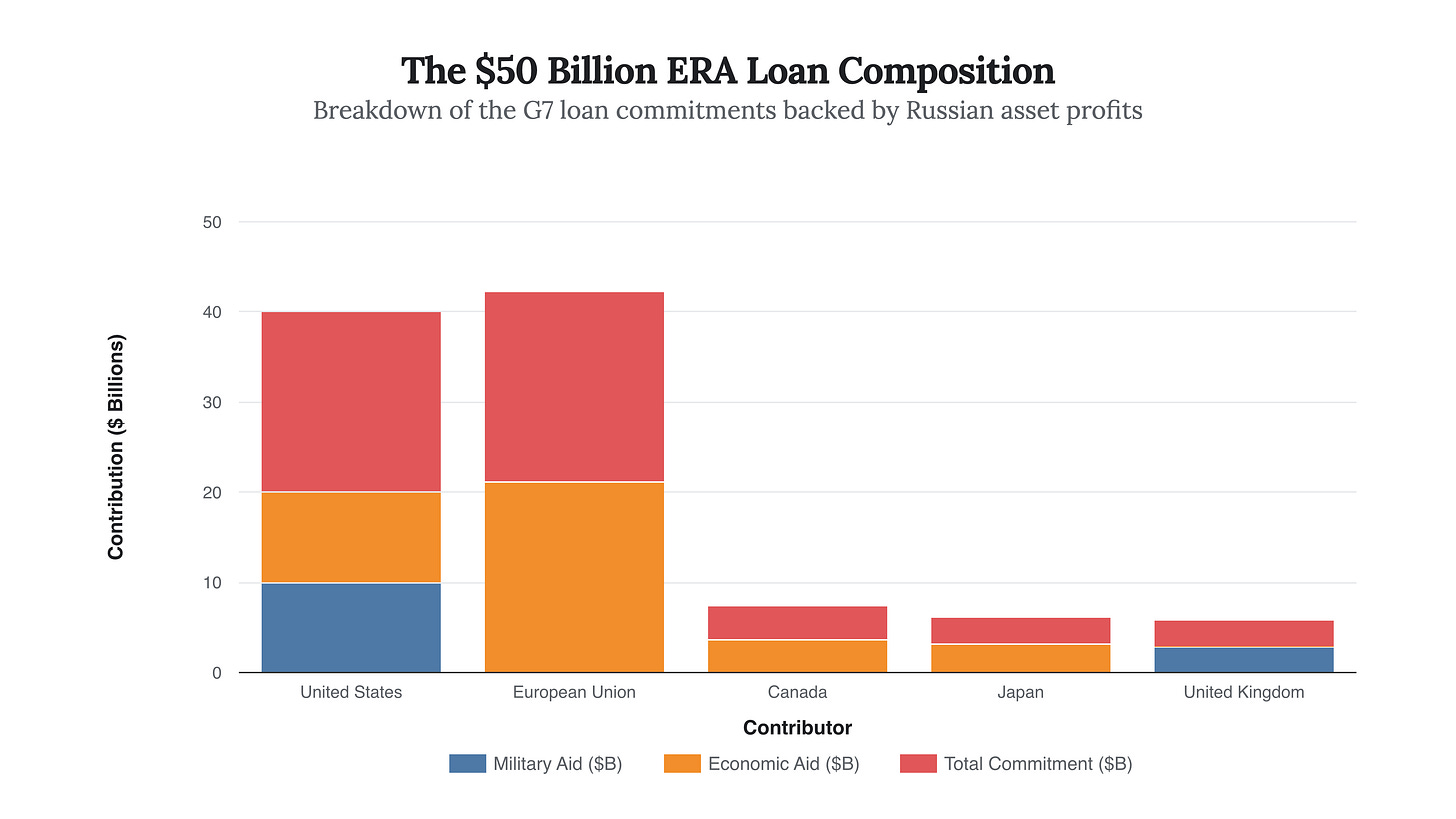

Instead of confiscation, the G7 settled on the “Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration” (ERA) loans. This mechanism is built on a legal distinction that separates the capital from the fruit. The theory posits that while the €210 billion principal belongs to Russia, the billions in interest generated by that cash sitting in Euroclear do not. By taxing and seizing this interest, the West can fund Ukraine without technically “stealing” the underlying asset.

The result is a $50 billion loan package, finalized in late 2024, where the principal is advanced by G7 nations but repaid entirely by these future Russian interest payments.

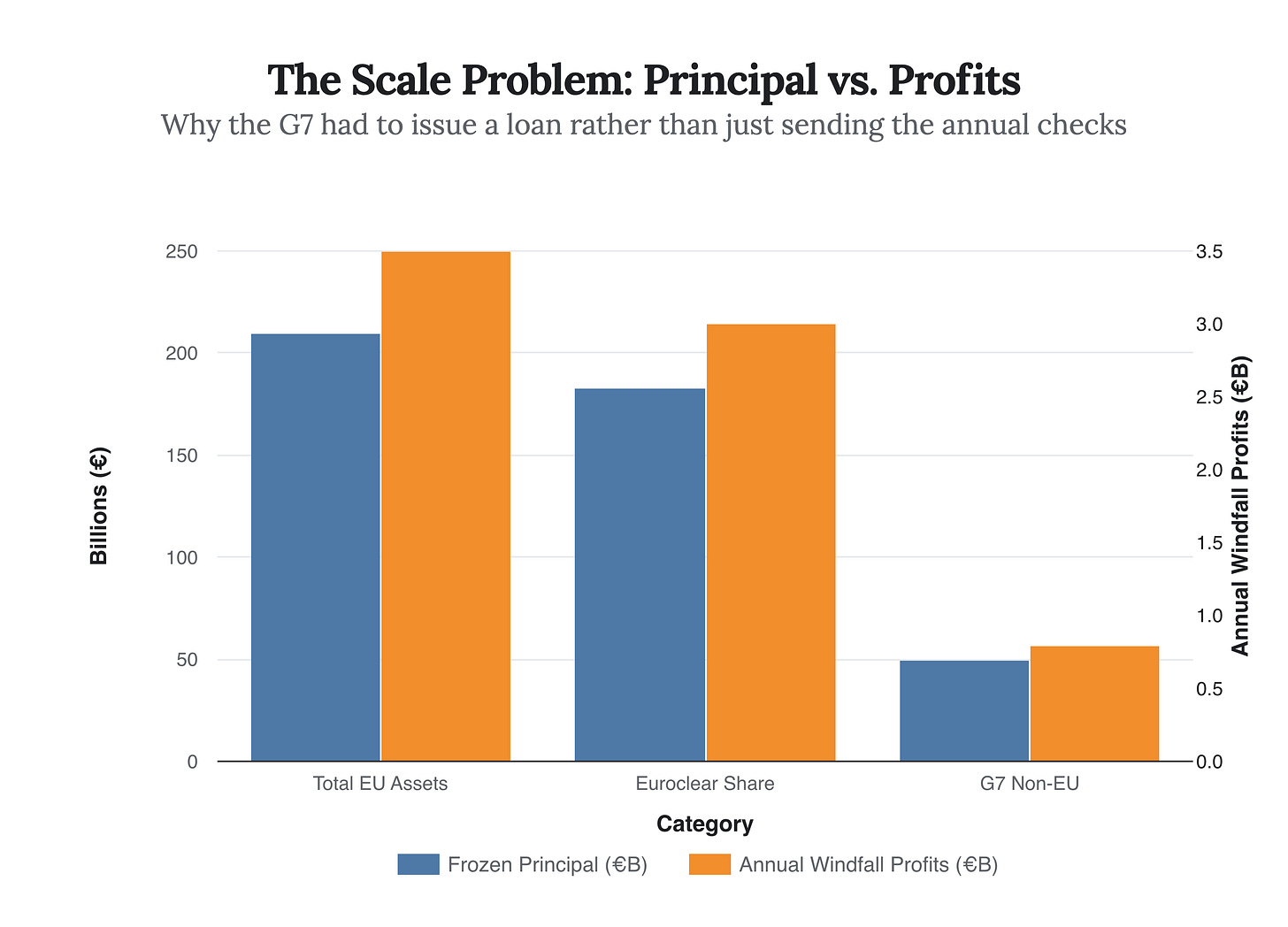

The mechanics of this loan expose the slow burn of the “windfall” approach versus the immediate impact of confiscation. The immobilized assets generate roughly €3 billion to €5 billion annually in interest, depending on interest rates. This is a significant sum, but it pales in comparison to the €210 billion principal. The “stealing option” would have provided an immediate, massive injection of cash. The “windfall option” effectively securitizes a trickle of income into a lump sum today.

This creates a “duration risk.” For the loan to be repaid fully by Russia (and not Western taxpayers), the assets must remain frozen for decades. If a peace deal is signed in 2026 that unfreezes the assets, the revenue stream dries up. This is why the US demanded assurances that the EU sanctions renewal period be extended from six months to three years—a move famously complicated by Hungarian veto threats.

The data in the chart above illustrates the “flow problem.” The annual windfall (the red line, if plotted) is barely visible against the towering column of the principal. Without the $50 billion loan mechanism to pull that future value forward, the annual interest payments would cover less than a month of Ukraine’s war effort.

We are now in uncharted legal waters. While the “stealing option” was avoided to protect the Euro, the current path still carries immense risk. Russia has already begun retaliatory seizures of Western assets within its borders, targeting companies like UniCredit. Furthermore, Euroclear is now facing a barrage of lawsuits in Russian courts. The West has effectively mortgaged a future it does not fully control, betting that the legal separation of “interest” from “principal” will hold up under the pressure of geopolitics.

The $50 billion loan is not just a financial lifeline; it is a gamble that the West can rewrite the rules of sovereign property without breaking the global financial system.

High stakes.