The Peninsula’s New Apex Predator: Analyzing the High-Stakes Calculus of a U.S.-South Korean Nuclear Submarine Pact

A deep dive into whether arming an ally will forge an ironclad deterrent or trigger a catastrophic arms race in the Indo-Pacific.

In a dramatic policy shift that redefines the contours of Indo-Pacific security, the United States has given a green light to South Korea for the development of nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs). Announced during a high-stakes summit, this landmark agreement involves direct U.S. technical support and a massive South Korean investment into the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base. The decision is a direct response to the dual threats of North Korea’s rapidly advancing nuclear arsenal and China’s expanding naval dominance.

However, this move to empower a key ally with one of America’s most sensitive military technologies is a monumental gamble. It aims to create a powerful, asymmetric deterrent on China’s doorstep, but it simultaneously risks shattering the fragile nuclear non-proliferation regime, provoking a furious reaction from Beijing and Pyongyang, and igniting a multi-polar underwater arms race that could destabilize the entire region. This briefing deconstructs the strategic calculus behind this decision, analyzes the immense technical and geopolitical hurdles, and provides foresight into the second-order effects for regional stakeholders.

The Geopolitical Crucible: Forging a New Deterrent in Turbulent Waters

The decision to equip South Korea with nuclear submarine technology did not occur in a vacuum. It is the culmination of years of escalating threats and a fundamental reassessment of the security architecture in Northeast Asia. For Seoul, the strategic imperative has become undeniable, driven by factors that threaten its very survival.

The Ever-Present Threat from the North

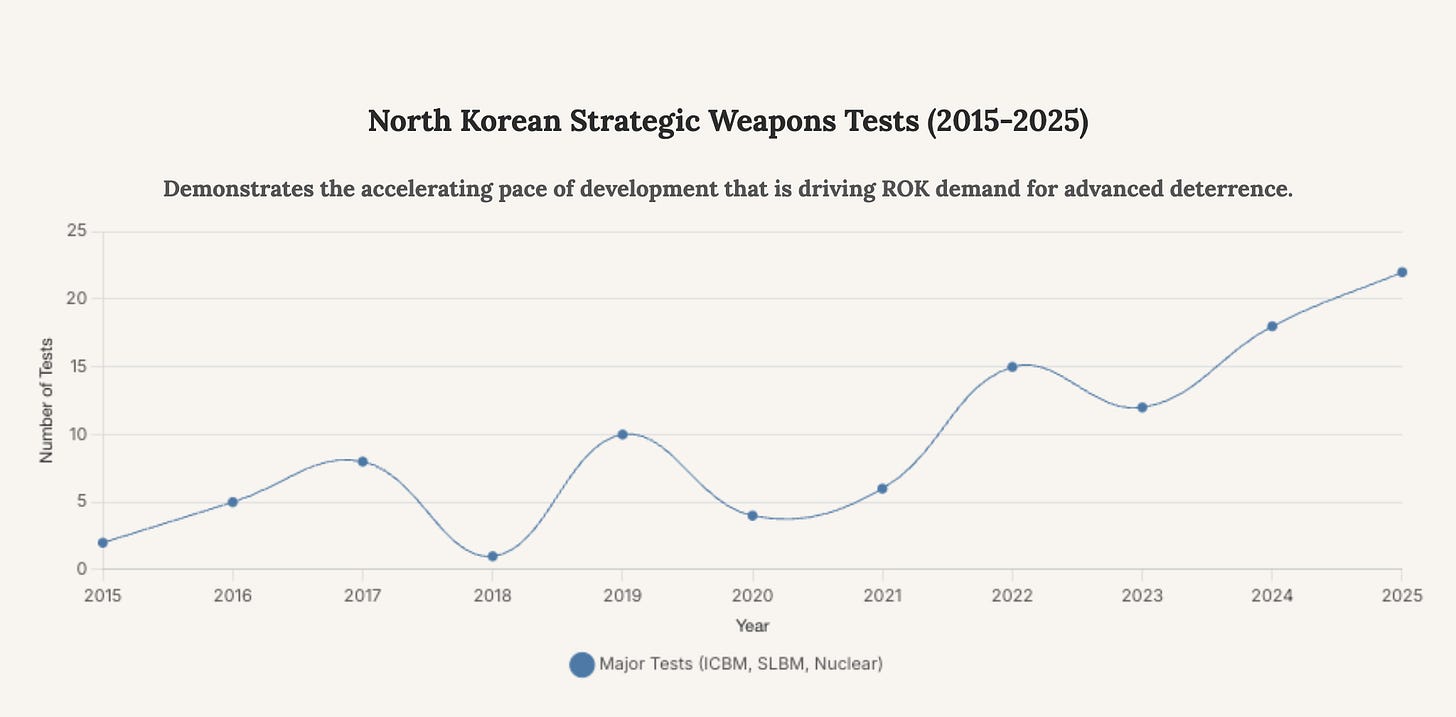

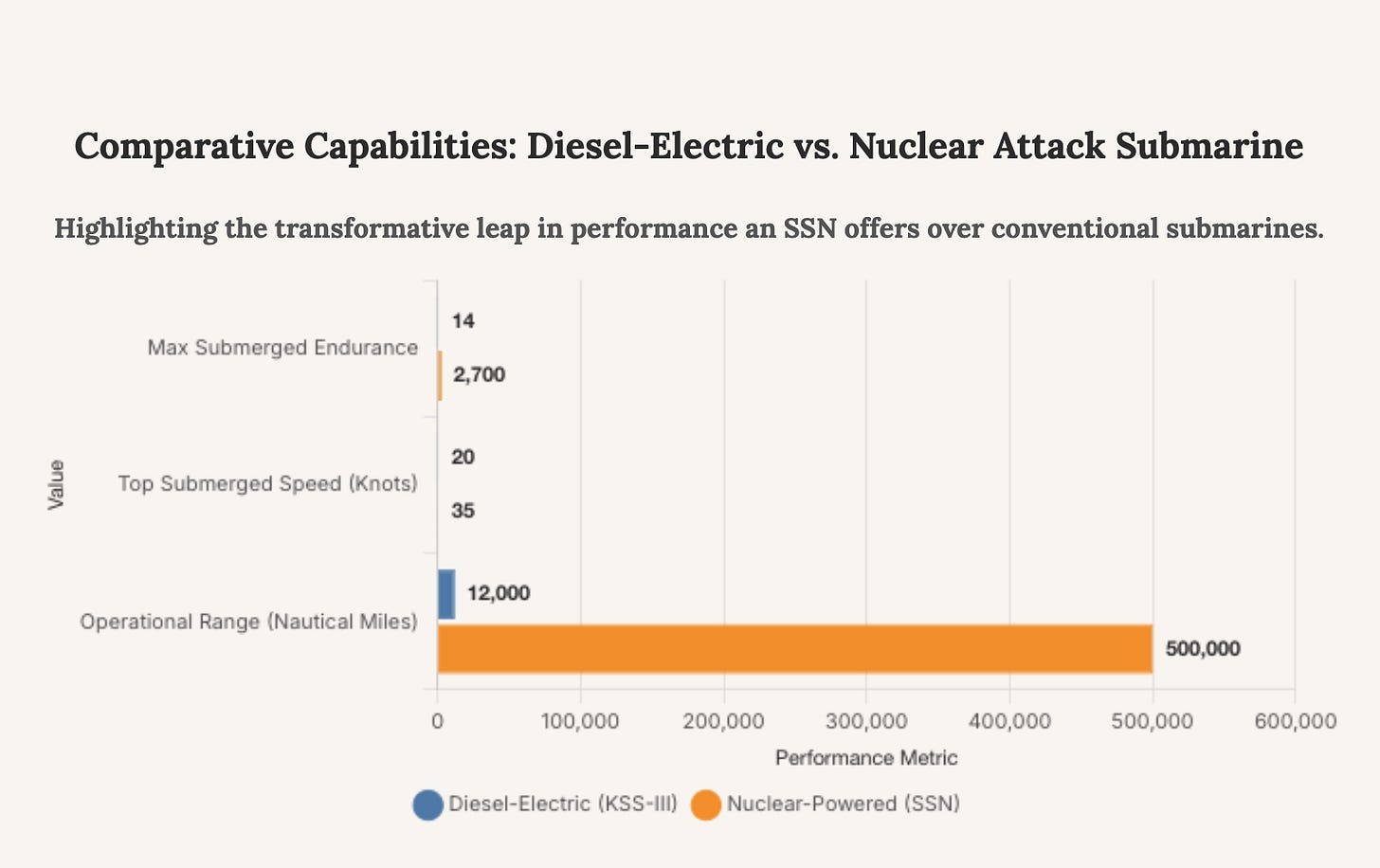

The primary catalyst for Seoul’s ambition is the relentless modernization of North Korea’s military capabilities. Pyongyang has moved far beyond rudimentary provocations, now possessing a credible submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capability and having recently unveiled its own purported nuclear-powered submarine. This gives North Korea a potential second-strike capability, significantly complicating deterrence calculations for the U.S.-ROK alliance. Conventional diesel-electric submarines, which must surface or snorkel to recharge batteries, are at a severe disadvantage when it comes to tracking their nuclear-powered counterparts, which can remain submerged for months at a time. This growing asymmetry has convinced South Korean leadership that only an SSN fleet can provide the persistent, stealthy surveillance needed to neutralize the North Korean SLBM threat.

The sharp increase in North Korean strategic weapons testing has fundamentally altered South Korea’s security calculus, making the limited endurance of its conventional submarine fleet a critical vulnerability.

Counterbalancing China’s Naval Ascendancy

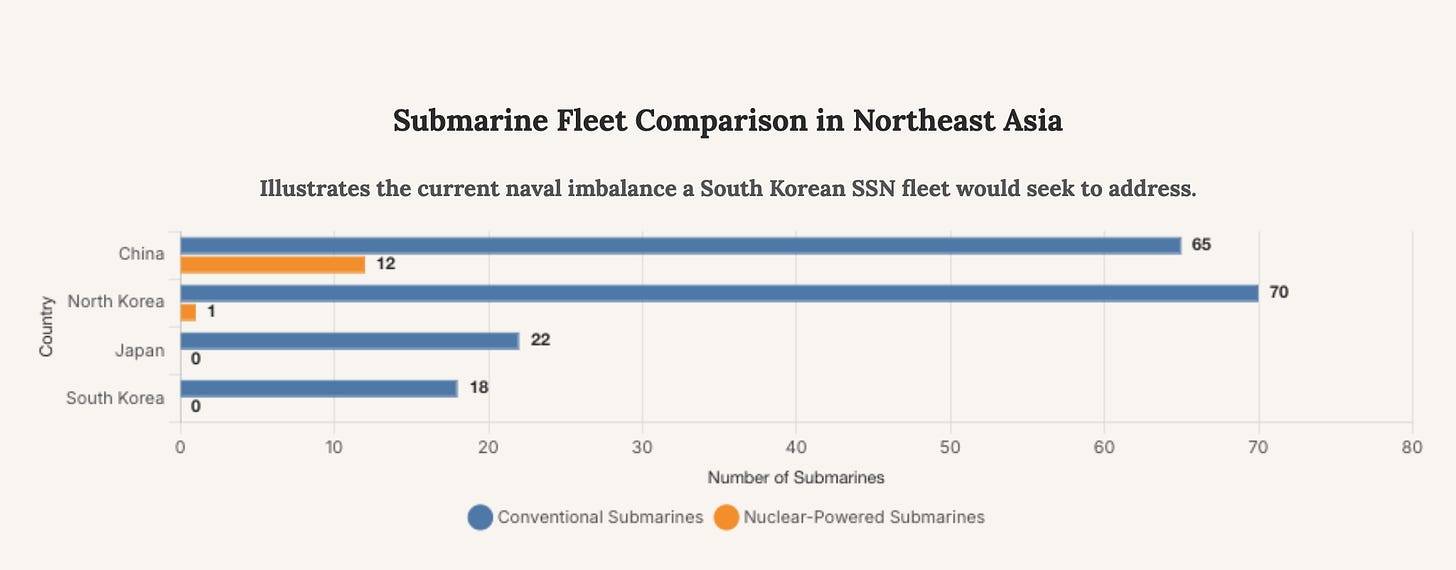

While North Korea provides the immediate justification, the broader strategic context is China’s emergence as a dominant naval power. Beijing now commands the world’s largest navy and is increasingly assertive in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. South Korean President Lee Jae Myung explicitly noted the difficulty of tracking Chinese submarines with his country’s current fleet, a comment that underscored the dual-use nature of the SSN ambition. For Washington, empowering South Korea to patrol its own littoral waters with highly capable platforms serves a dual purpose: it strengthens a key ally and creates a potent deterrent that complicates China’s maritime operations, effectively increasing the ‘cost’ of any aggression. This aligns with a broader U.S. strategy of building a network of empowered allies—similar to the AUKUS pact with Australia—to collectively balance China’s power.

China’s substantial fleet, including a growing number of SSNs, and North Korea’s large conventional force create significant pressure on South Korea and Japan, who currently operate no nuclear-powered vessels.

The Pandora’s Box Protocol: Navigating Immense Hurdles

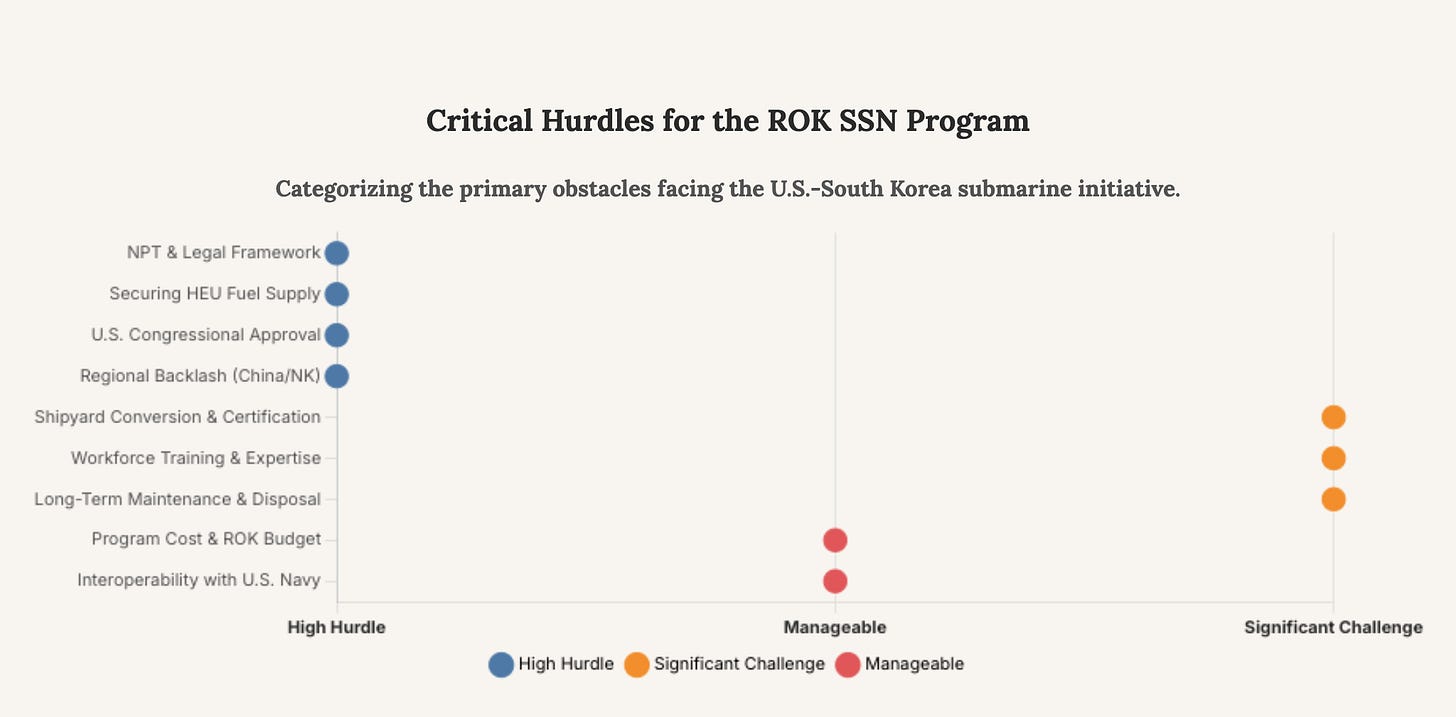

Despite the strategic logic, the path to a South Korean SSN fleet is fraught with immense technical, financial, and diplomatic challenges. The announcement is merely the first step in a decadelong process that could be derailed at numerous points.

“As with the AUKUS deal, (South Korea) is probably looking for nuclear propulsion services suitable for subs, including the fuel, from the U.S. Such submarines usually involved the use of highly-enriched uranium and would require a very complex new regime of safeguards by the International Atomic Energy Agency.”

- Daryl Kimball, Executive Director, Arms Control Association

The Non-Proliferation Minefield

The single greatest obstacle is the global nuclear non-proliferation regime. The U.S.-ROK bilateral atomic energy agreement, the so-called “123 Agreement,” strictly prohibits South Korea from enriching uranium or reprocessing spent fuel for military purposes without explicit U.S. consent. Providing nuclear fuel for submarines—especially if it is highly-enriched uranium (HEU), the standard for U.S. submarines—creates a complicated precedent. Critics argue it could weaken the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), as the technology for naval reactors is intrinsically linked to weapons capabilities. China has already called on both Washington and Seoul to uphold their non-proliferation obligations. Seoul has been quick to assert that its ambitions are for propulsion, not weapons, but this distinction may not satisfy regional rivals.

The path forward is dominated by high-level political and legal challenges, particularly concerning non-proliferation and securing the necessary U.S. legislative support, which outweigh the (still significant) industrial and technical hurdles.

The Industrial and Financial Equation

The deal’s structure is unique: the submarines are to be built not in South Korea, but at the Hanwha-owned Philly Shipyard in the United States. This is tied to a massive $350 billion South Korean investment package, with $150 billion specifically earmarked to revitalize the American shipbuilding industry. However, the Philly Shipyard is a commercial facility not currently equipped for nuclear military construction. The overhaul required to meet the stringent safety and security standards for nuclear work will take years and a massive investment in infrastructure and a skilled workforce. This comes at a time when the U.S.’s own submarine industrial base is already strained, facing two- to three-year backlogs on its own Virginia-class submarines. Experts estimate the program will take at least a decade to produce the first vessel.

The difference in submerged endurance is the most critical strategic advantage. An SSN’s ability to remain underwater for months, limited only by crew provisions, makes it a fundamentally different and more potent asset for anti-submarine warfare and deterrence patrols.

The Ripple Effect: Mapping Geopolitical Consequences

The decision to proceed will create powerful and unpredictable ripples across the Indo-Pacific, forcing regional powers to reassess their own strategic postures. The reaction from rivals is certain to be hostile, while even allies may grow uneasy.

Beijing’s Fury and Pyongyang’s Paranoia

China and North Korea will view this development as a major provocation. For Pyongyang, it justifies its own nuclear program as a necessary defense against a technologically superior adversary. For Beijing, a fleet of advanced South Korean SSNs, operating in coordination with U.S. and potentially Japanese forces, represents a grave new threat in its maritime backyard. This could trigger an accelerated naval buildup by China and more aggressive military posturing in the region, creating a dangerous spiral of escalation. While Beijing’s initial reaction has been measured, this is likely a temporary stance ahead of diplomatic engagements and does not reflect its long-term strategic assessment.

Tokyo’s Strategic Dilemma

The deal places Japan in a difficult position. While also a close U.S. ally concerned about China and North Korea, the prospect of a nuclear-powered South Korean navy introduces a new element of regional competition. It will undoubtedly fuel debate within Japan about its own military capabilities and its pacifist constitution. There are already factions within the Japanese government advocating for acquiring similar next-generation propulsion systems. A South Korean SSN could tip the scales in favor of Japan pursuing its own nuclear submarine program, a move that would further intensify a regional arms race.

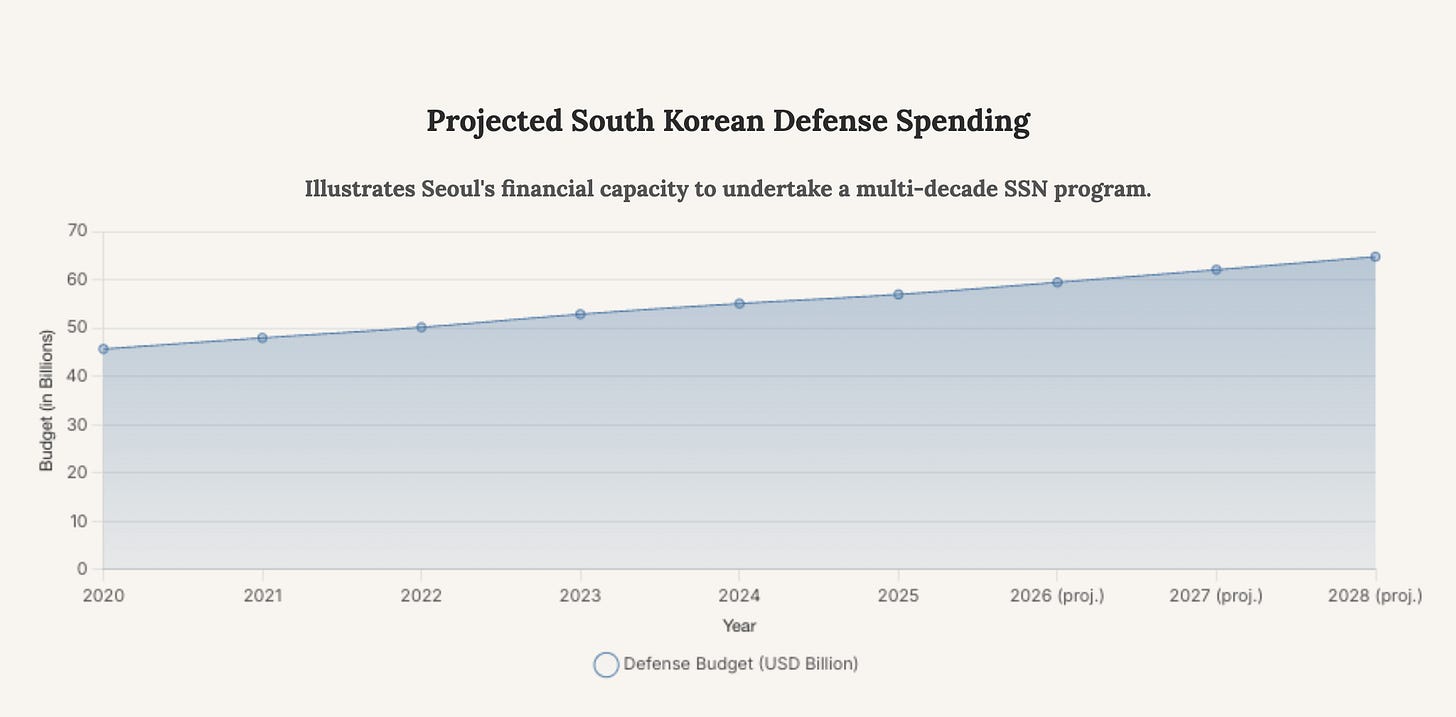

South Korea’s steadily increasing defense budget demonstrates a long-term commitment to military modernization, suggesting the political will exists to fund the enormous costs associated with developing, acquiring, and maintaining a nuclear submarine fleet.

Strategic Foresight and Key Signposts

The U.S.-ROK SSN agreement has set in motion a chain of events that will unfold over the next decade. For policymakers and investors, several key signposts will indicate the program’s trajectory and its wider strategic impact.

“In the end, this South Korea-U.S. summit can be summarized in one word: the commercialization of the alliance and the commodification of peace. The problem is that the balance of that deal was to maximize American interests rather than the autonomy of the Korean Peninsula.”

- Kim Dong-yup, Professor, Kyungnam University

First, watch the U.S. Congress. The technology transfer and fuel supply agreements will require legislative approval, which is not guaranteed. A contentious debate is expected, pitting proponents of strengthening alliances against staunch advocates for non-proliferation. Second, monitor the progress at the Philly Shipyard. The ability to successfully convert the commercial yard into a nuclear-certified facility will be the program’s primary logistical bellwether. Delays here will signal broader problems. Third, observe China’s naval deployments and shipbuilding rates. A significant acceleration in its production of SSNs or a more aggressive permanent posture in the Yellow Sea would indicate that Beijing perceives the ROK program as a strategic threat that must be countered directly. Finally, pay close attention to the political discourse in Japan. Any official move to revise its interpretation of its constitution or formally commission studies on nuclear propulsion would be a clear signal that a wider, regional proliferation cascade is underway.

The U.S. has made a calculated decision to trade proliferation risk for what it hopes will be a decisive strategic advantage in Northeast Asia. By providing South Korea with the ultimate conventional deterrent, Washington is placing a major bet on its ability to manage the fallout. This initiative will fundamentally reshape the U.S.-ROK alliance from one of protection to one of empowerment, but it does so by crossing a technological Rubicon. The coming years will reveal whether this bold move creates a stable, deterred peace or unleashes competitive dynamics that spiral out of control. The era of proxy deterrence is over; the age of direct allied empowerment has begun, and its consequences will define the 21st-century strategic landscape.