The 95% Collapse: How Beijing’s ‘Delete America’ Campaign Is Forging a New World Order in AI

An in-depth analysis of China’s escalating ban on foreign technology and its strategy to achieve semiconductor sovereignty by 2027

In the high-stakes world of artificial intelligence, market dominance can evaporate in a geopolitical blink. For Nvidia, that blink has erased a staggering 95% of its once-commanding share of the Chinese AI chip market, a collapse from near-total control in 2022 to virtually zero today. This is not a standard market fluctuation; it is the most visible outcome of a deliberate, multi-pronged, and rapidly accelerating campaign by Beijing to systematically eradicate foreign technology from its critical infrastructure.

What began as a government PC replacement program has metastasized into a full-blown industrial strategy, now targeting telecom networks, state-owned enterprises, and, most critically, the state-funded data centers that form the bedrock of China’s AI ambitions. This analysis deconstructs Beijing’s strategy, revealing a calculated plan that leverages state purchasing power and massive energy subsidies to build a self-reliant, state-controlled technology ecosystem. The implications extend far beyond the balance sheets of Intel, AMD, and Nvidia, signaling the definitive end of a unified global tech standard and the dawn of a bifurcated, and far more volatile, technological world order.

The 2027 Mandate: Deconstructing Beijing’s Tech Offensive

Beijing’s push for technological autarky, often referred to as ‘Xinchuang’ (IT application innovation), has evolved from a long-term aspiration into a hard-deadline mandate. Recent directives have created a clear timeline and a multi-front offensive aimed at systematically replacing Western hardware and software across the nation’s most sensitive sectors. This is no longer a piecemeal effort but a coordinated, whole-of-government campaign with a clear end-state: a technology stack built and controlled by Chinese entities.

Government & SOE Procurement: The ‘Xinchuang’ Foundation

The initial and most public phase of the ban targeted the nerve center of the state itself. In late 2023, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the Ministry of Finance quietly issued procurement guidelines for government agencies and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). These guidelines effectively ban the use of microprocessors from U.S. giants Intel and AMD in government PCs and servers. The directive extends beyond just CPUs, also targeting Microsoft’s Windows operating system and other foreign-made database software in favor of domestic alternatives. To enforce this, the China Information Technology Security Evaluation Center released a list of “safe and reliable” processors and operating systems, comprised exclusively of Chinese companies like Huawei and Phytium. This foundational move creates a protected, guaranteed market for domestic champions, allowing them to scale and mature under state patronage.

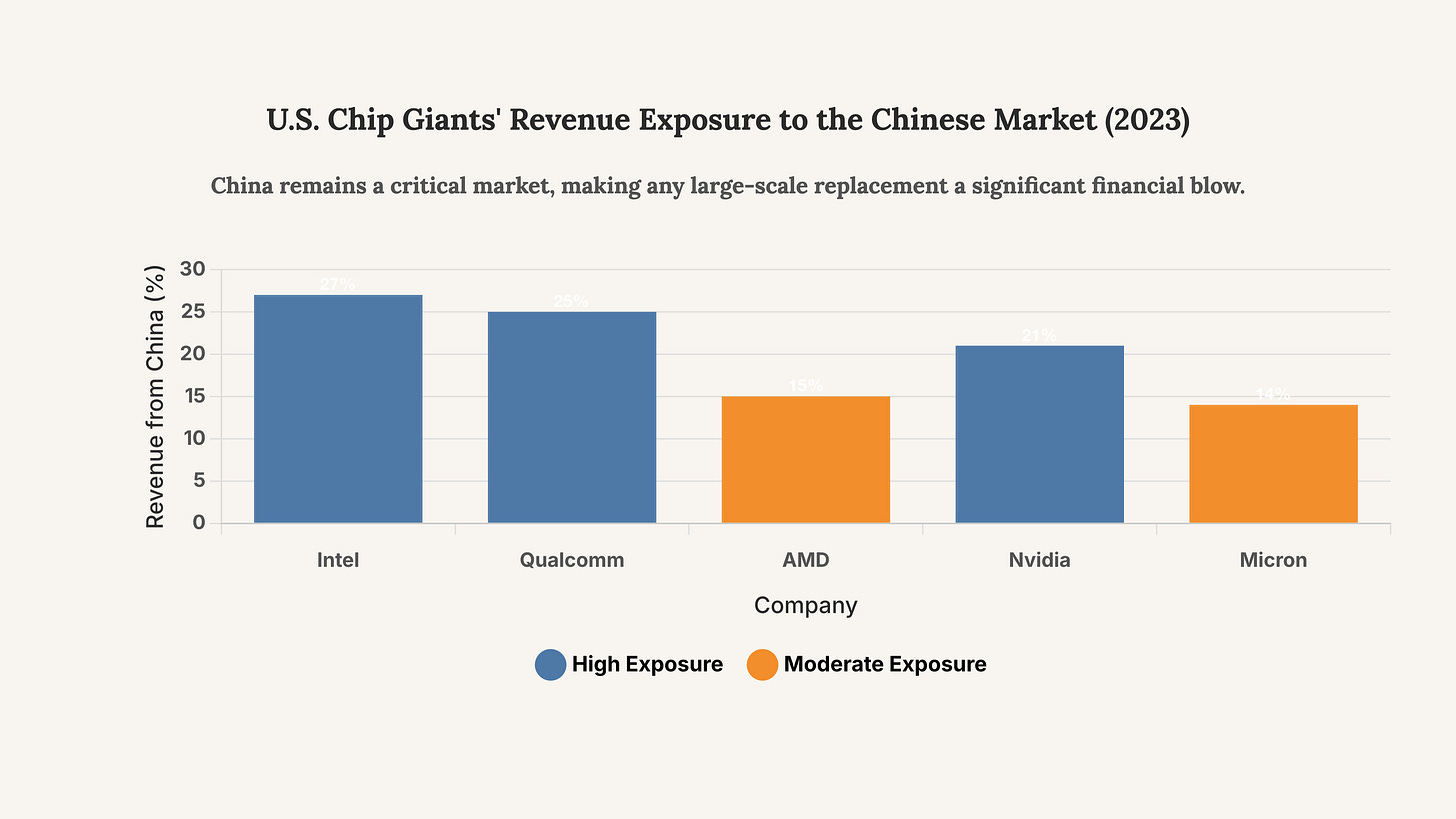

The significant revenue dependency of major U.S. semiconductor firms on the Chinese market highlights the profound financial stakes of Beijing’s technology replacement campaign.

The Telecom Overhaul: Ripping and Replacing the Network Core

The campaign dramatically escalated in early 2024 when the MIIT ordered China’s largest state-owned telecom operators—including China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom—to phase out foreign core processors from their networks by a firm deadline of 2027. This directive strikes at the heart of the nation’s digital backbone. Carriers were instructed to inspect their networks for non-Chinese semiconductors and draft explicit timelines for their replacement. This move targets the highest-value chips from Intel and AMD, which have long dominated the networking equipment space globally. The 2027 deadline transforms the gradual ‘Xinchuang’ policy into an urgent, non-negotiable infrastructure overhaul, forcing a rapid transition to domestic silicon for the country’s massive 5G and future 6G networks.

State-Funded AI: The Newest Front in the Data Center Wars

Most recently, and perhaps most significantly for the future of AI, Beijing has extended the ban to the engine rooms of the digital economy: data centers. New government guidance requires any new data center project that receives state funding to use exclusively domestically produced AI chips. The rules are ruthlessly retroactive for projects already underway: those less than 30% complete have been ordered to remove all foreign chips and cancel any outstanding purchase plans. This is a direct assault on Nvidia’s remaining foothold in the market and a powerful boost for domestic AI chipmakers like Huawei. By tying state investment—the primary funding source for large-scale infrastructure—to the use of local hardware, Beijing is engineering demand for its domestic AI chip industry on an enormous scale.

The Sovereignty Gambit: Ambition vs. Reality

Executing this technological secession is a monumental undertaking. For years, the primary obstacle to replacing foreign chips has been the significant performance gap of domestic alternatives. Beijing’s strategy acknowledges this reality but seeks to overcome it through a combination of brute-force investment, a redefinition of performance requirements, and a focus on capturing specific, less advanced segments of the market where it can compete effectively.

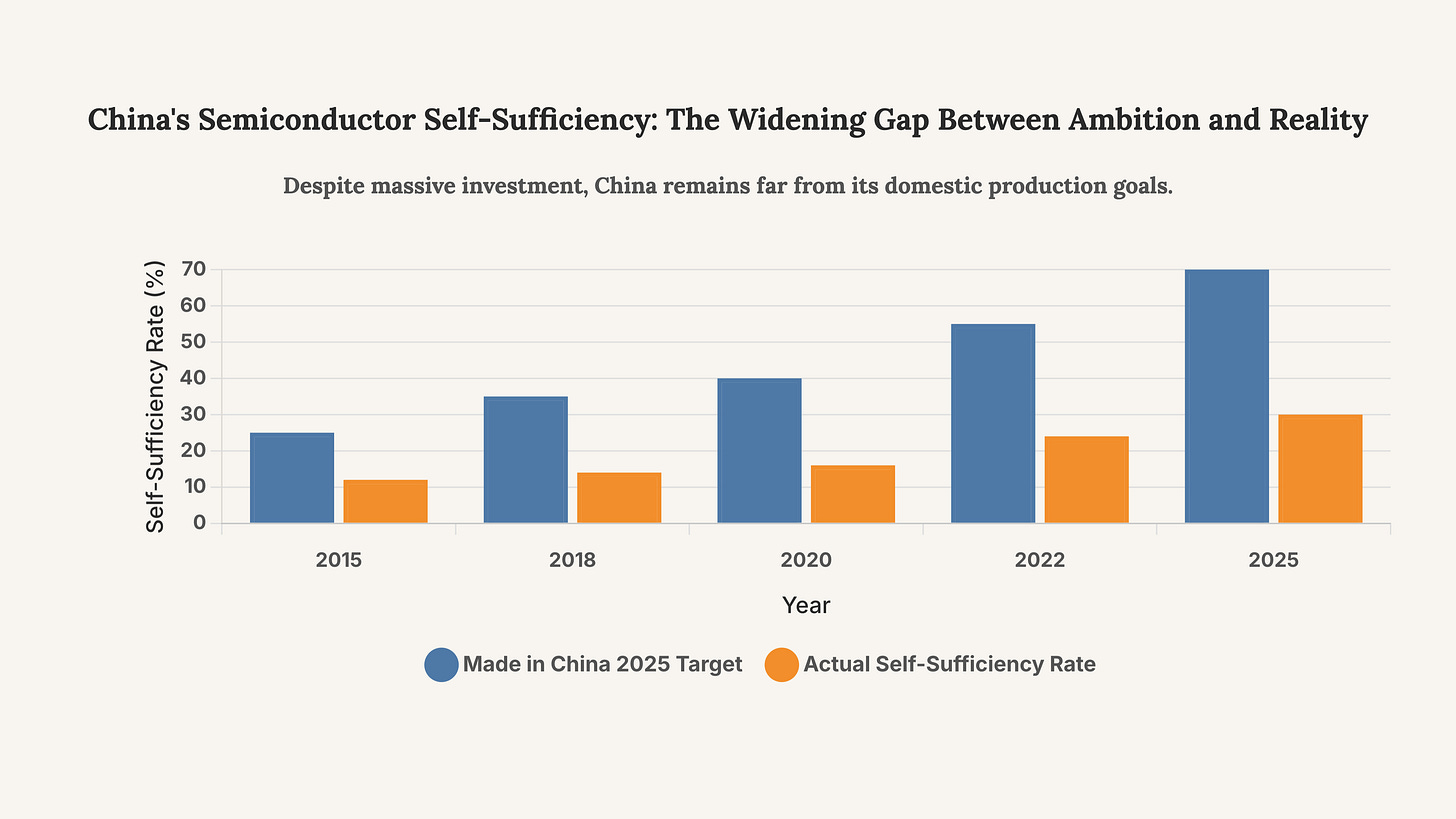

The ‘Made in China 2025’ Doctrine: Closing the Self-Sufficiency Gap

This entire campaign is the operationalization of the ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy, which set an ambitious target of achieving 70% self-sufficiency in semiconductors by 2025. The reality has fallen far short, with estimates suggesting China’s domestic production only met around 30% of its needs by the target year. This glaring gap is the driving force behind the recent flurry of aggressive mandates. To close it, China has deployed massive state capital through its National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, or “Big Fund,” which has funneled over a hundred billion dollars into the sector since 2014. The goal is no longer just to participate in the global market, but to build a parallel, self-sufficient ecosystem immune to U.S. export controls.

China’s ambitious goals for semiconductor self-sufficiency, a cornerstone of its industrial policy, have consistently outpaced the actual growth of its domestic production capabilities.

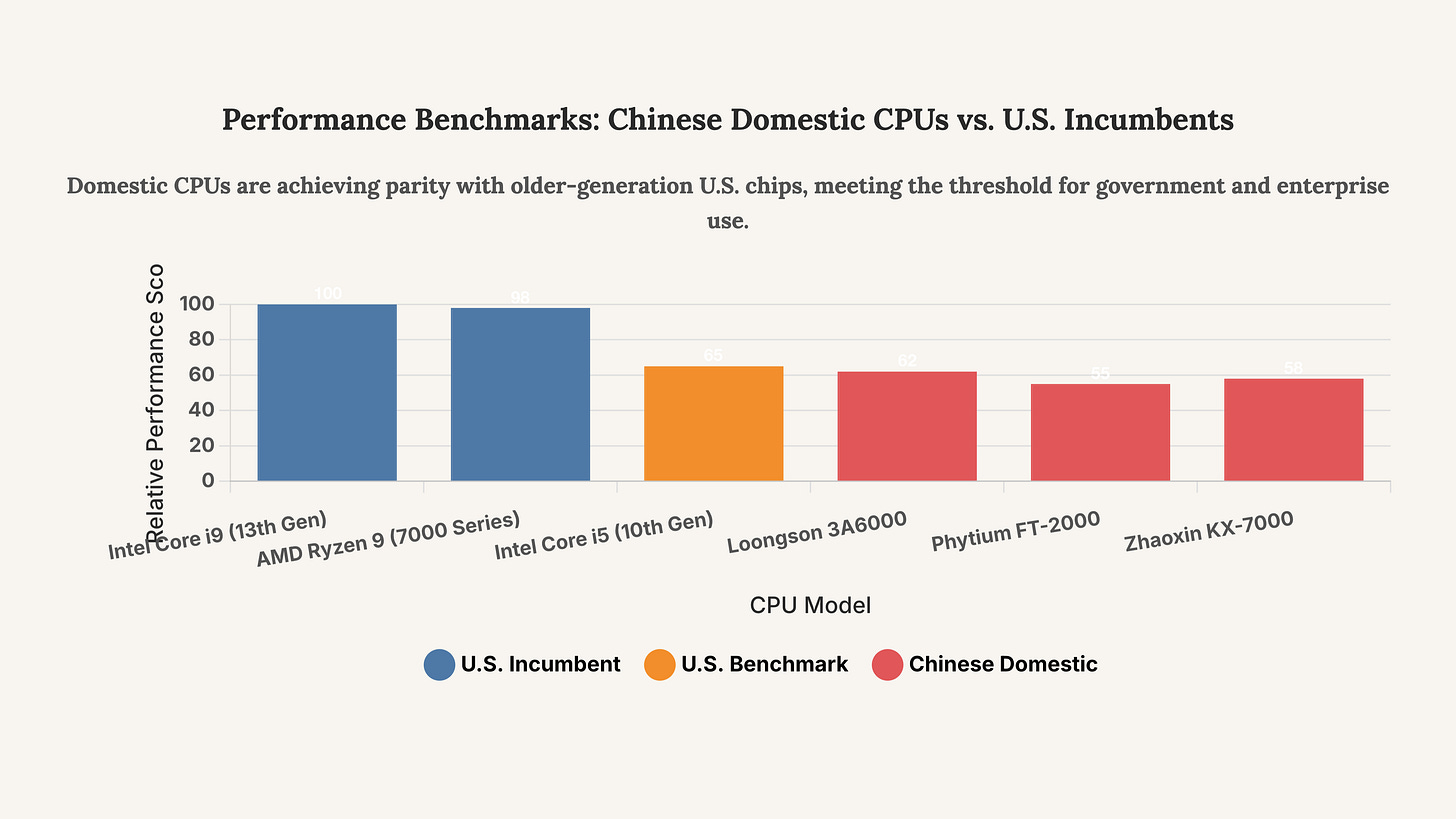

The Performance Paradox: When ‘Good Enough’ Becomes National Policy

While Chinese CPUs have historically lagged their U.S. counterparts by several generations, recent progress has been notable. Domestic champions like Loongson are now producing chips, such as the 3A6000, that demonstrate Instructions Per Cycle (IPC) performance approaching modern AMD and Intel architectures. However, they are hampered by lower clock speeds and less mature manufacturing processes. The Loongson 3A6000, for example, is often benchmarked as being comparable to an Intel 10th-generation Core processor from 2020. For cutting-edge AI or high-performance computing, this is inadequate. But for the vast majority of government desktop computers, servers, and administrative tasks, this level of performance is increasingly seen as “good enough.” Beijing is making a strategic bet that absolute top-tier performance is unnecessary for most state functions and that security and supply chain control are paramount.

While China’s leading domestic CPUs still lag behind the latest high-end U.S. processors, they are now competitive with mainstream chips from just a few years ago, making them viable replacements for many government and commercial applications.

“It is expected that xinchuang servers, which align with these new guidelines, will comprise 23 percent of China’s total server shipments by 2026.”

The New Economics of Decoupling: Carrots, Sticks, and Market Distortion

Beijing’s strategy is not based on technological parity alone. It is actively reshaping the economic incentives for its domestic tech giants, using a powerful combination of subsidies and mandates to make the transition to local silicon not just mandatory, but financially attractive. This economic engineering is designed to overcome the primary drawbacks of domestic chips: lower performance and higher operational costs.

The Energy Equation: Weaponizing Electricity Costs

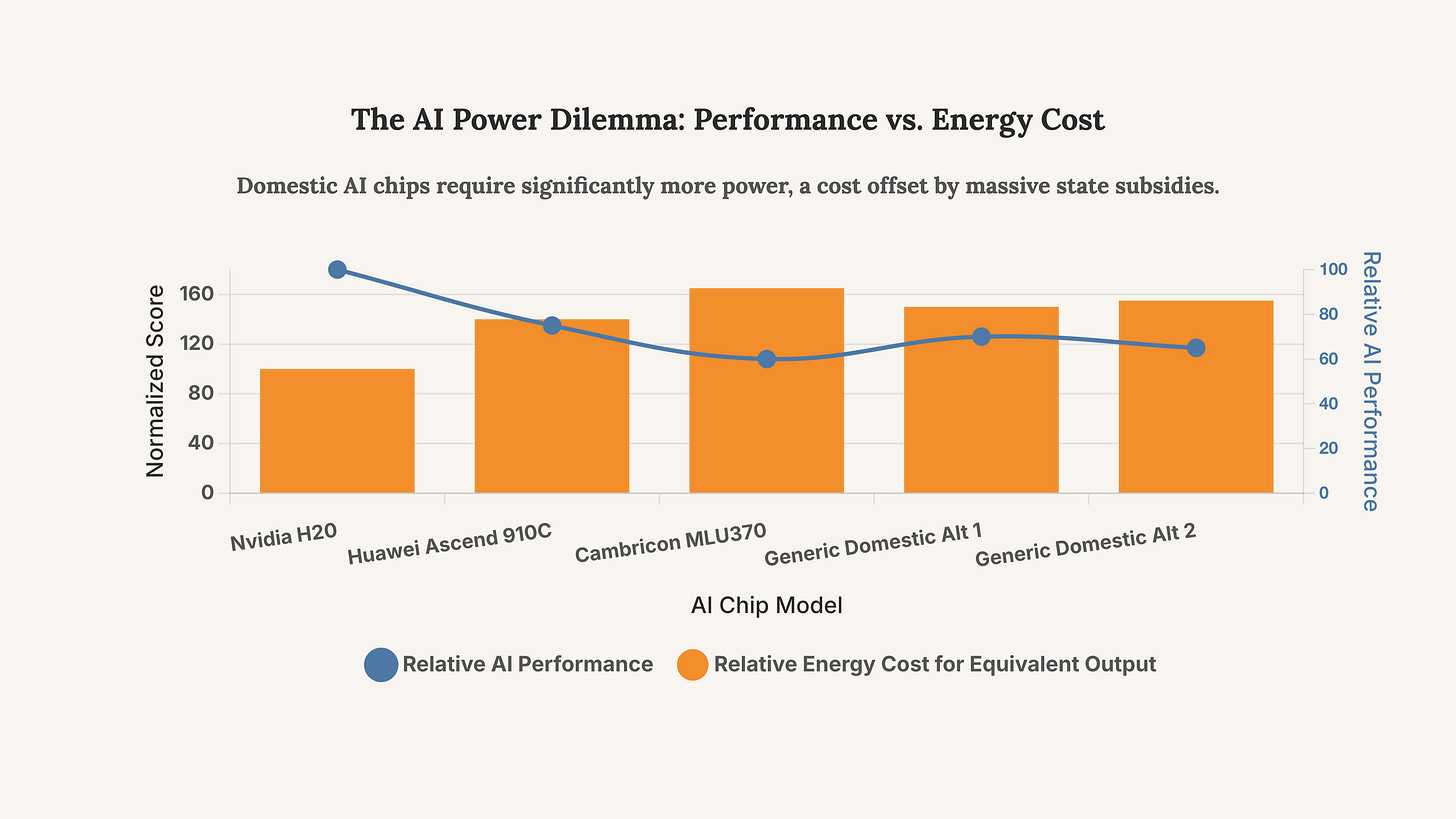

A critical, and often overlooked, factor in the AI chip race is energy efficiency. Current-generation Chinese AI chips are estimated to require 30-50% more electricity to deliver the same computational output as their Nvidia counterparts. For data center operators, where power is a primary operating expense, this is a massive financial burden. To counteract this, local governments in data center hubs are now offering staggering subsidies that can slash electricity bills by up to 50%. There is one crucial condition: these subsidies are available only to data centers running on domestic chips. This policy ingeniously turns a key weakness into a tool for enforcement, effectively subsidizing the inefficiency of domestic hardware and erasing the total-cost-of-ownership advantage of foreign chips.

“The core issue is energy efficiency. Experts estimate that generating the same amount of tokens...from the current generation of Chinese chips requires about 30-50% more electricity than the equivalent Nvidia H20 chip.”

This chart illustrates the trade-off facing Chinese tech firms. While domestic AI chips (like Huawei’s Ascend) are becoming more capable, they are significantly less power-efficient than foreign alternatives like Nvidia’s H20. The state’s energy subsidies are designed to nullify this disadvantage.

Strategic Foresight: Winners, Losers, and the Future of the Tech G2

This state-engineered decoupling is creating a new set of winners and losers and solidifying the bifurcation of the global technology landscape. The long-term effects will be a less efficient, more fragmented, but also potentially more resilient domestic tech industry in China, and a permanently smaller addressable market for Western firms.

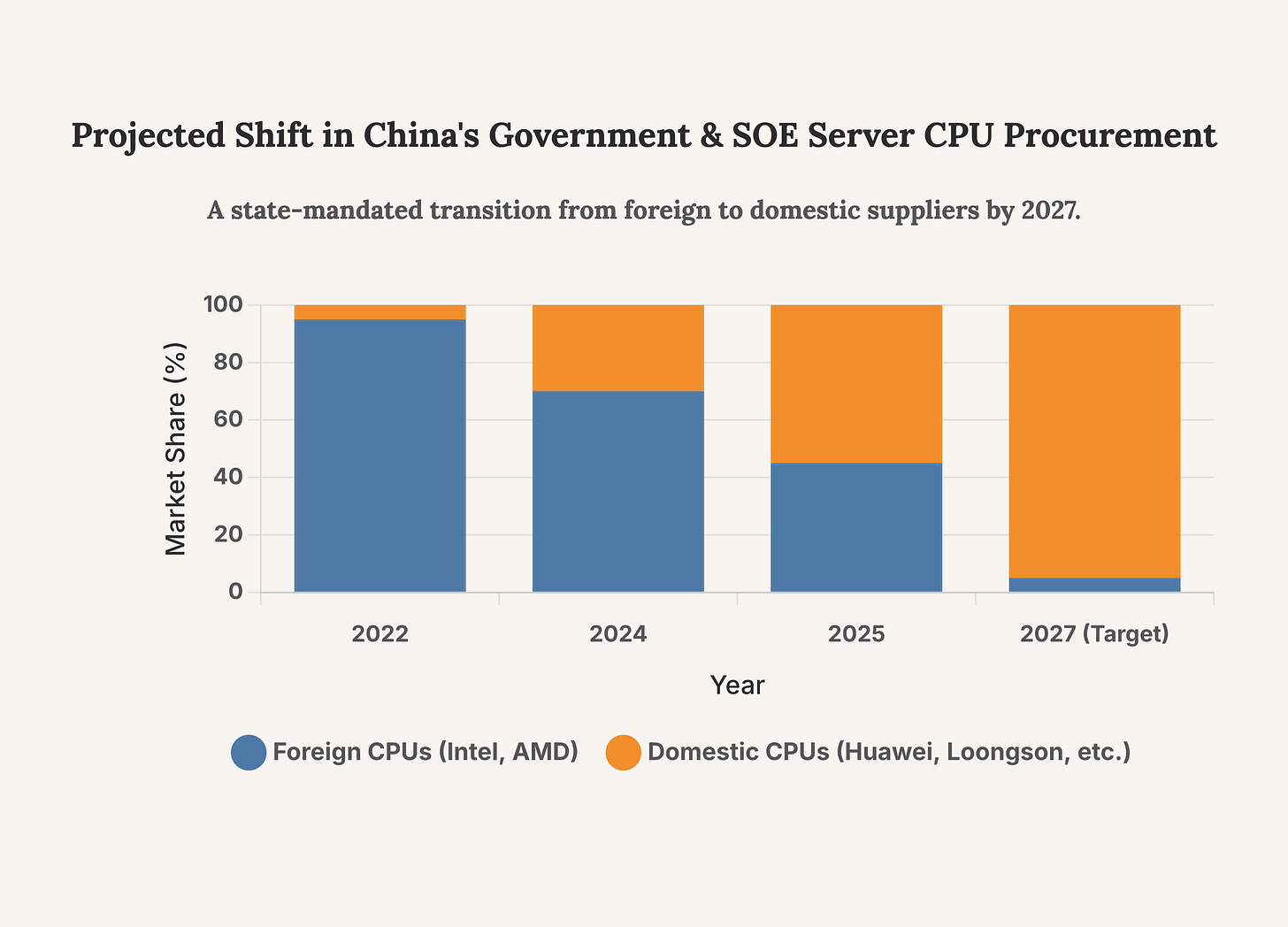

The trajectory is clear: state directives are forcing a rapid and near-total replacement of foreign CPUs within China’s government and state-owned enterprise sectors over the next three years.

The Winners: Domestic champions are the clear beneficiaries. Huawei (with its Kunpeng CPUs and Ascend AI chips), Loongson, Phytium, and Zhaoxin are being gifted a massive, protected domestic market, allowing them to achieve scale and reinvest in R&D without facing direct international competition in their home territory.

The Losers: U.S. tech giants face the permanent loss of a significant market segment. For Intel and AMD, the government, SOE, and telecom sectors represent billions in lost revenue. For Nvidia, the dream of powering China’s AI revolution is over, replaced by the reality of being designed out of the system entirely.

Key Signposts to Watch: Investors and policymakers should monitor several key indicators: the actual pace of chip replacement in telecom networks against the 2027 deadline; performance benchmarks of the next generation of Loongson and Huawei chips; and whether these restrictions begin to bleed into the private sector, particularly among large tech firms that work closely with the government.

Beijing’s strategy is a high-risk, high-reward gamble on technological sovereignty. It is trading near-term performance and efficiency for long-term control and immunity from foreign sanctions. The success of this gambit is not guaranteed; it hinges on the ability of its domestic industry to close the performance gap and innovate under pressure. But the directive is clear and the momentum is building. The era of US chip dominance inside China’s critical infrastructure is over, and a new, state-shaped market is being forged in its place.

The era of a single, globalized technology standard is over; the primary strategic challenge is now navigating the fractured landscape of two increasingly incompatible, state-backed ecosystems.

“Beijing is engineering demand for its domestic AI chip industry on an enormous scale.”

Really? And I dare ask, why is Beijing engineering this demand for domestic chips? If not for the trade wars and need for technological dominance imposed on it by the USA and the west? Why else would China seek self sufficiency, if its western partners had not proven themselves to be unreliable and bent on maintaining its hegemonic dominations over all spheres?