The ¥60 Trillion Paperweight: Why Japan’s Currency Reboot Triggered a Stealth Insolvency Crisis

A deep dive into the liquidity trap hiding behind the July 2024 banknote redesign

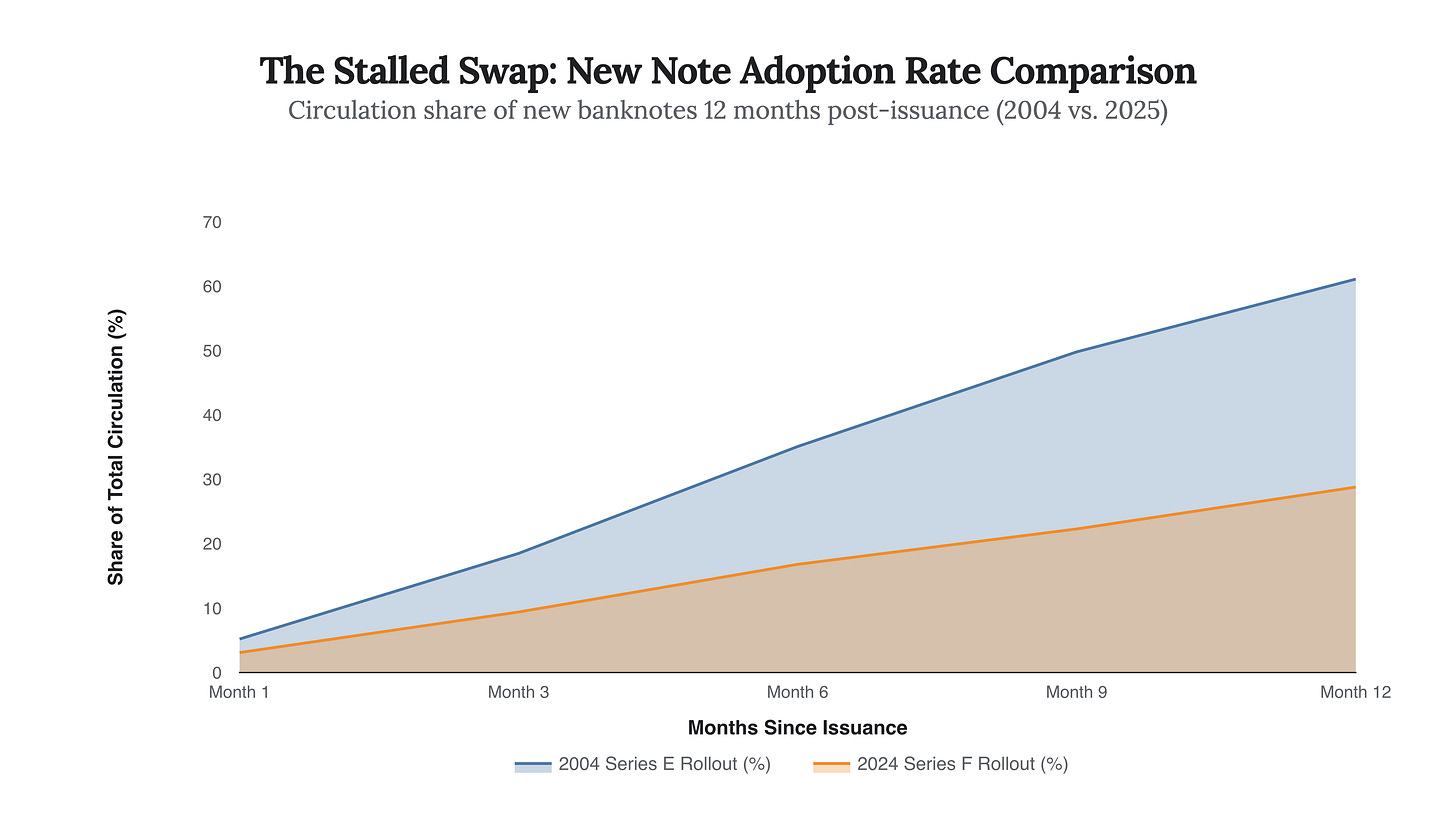

The most dangerous number in the Japanese economy today is not the yen’s exchange rate against the dollar, nor is it the yield on the 10-year JGB. It is 28.8%. That is the anemic circulation rate of the new banknotes one year after their highly publicized July 2024 launch—less than half the velocity seen during the last redesign in 2004. While the Bank of Japan (BOJ) framed the issuance of the new ¥10,000, ¥5,000, and ¥1,000 notes as a routine anti-counterfeiting update, the strategic reality is far more volatile. This was a calculated kinetic event designed to flush out the legendary tansu yokin (mattress money)—estimated at over ¥60 trillion ($385 billion)—and force a velocity spike in a stagnant economy.

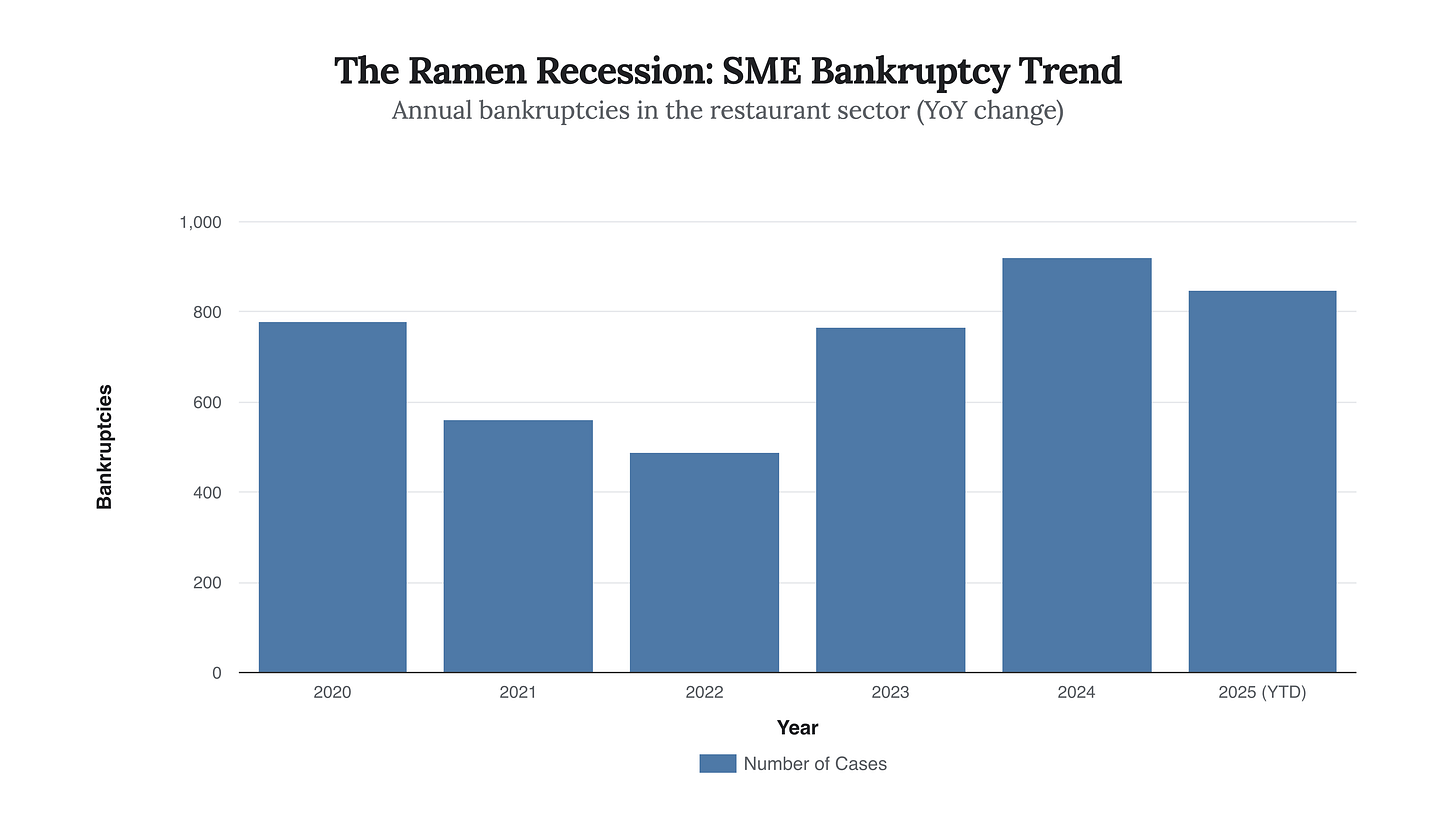

It has failed. Instead of unlocking hoarded wealth, the redesign has acted as a massive deflationary friction point, effectively imposing a Regressive CapEx Tax on the country’s most vulnerable Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). As we close 2025, the data reveals a stark bifurcation: the “Cashless Class” is accelerating away from the physical economy, while the “Cash Economy”—comprising millions of vending machines, ticket kiosks, and family-run eateries—is facing a forced obsolescence event. This is not just a story about printing money; it is a case study in how infrastructure friction can trigger structural inflation and business insolvency.

The Hardware Gap: A ¥1.6 Trillion Tax on Friction

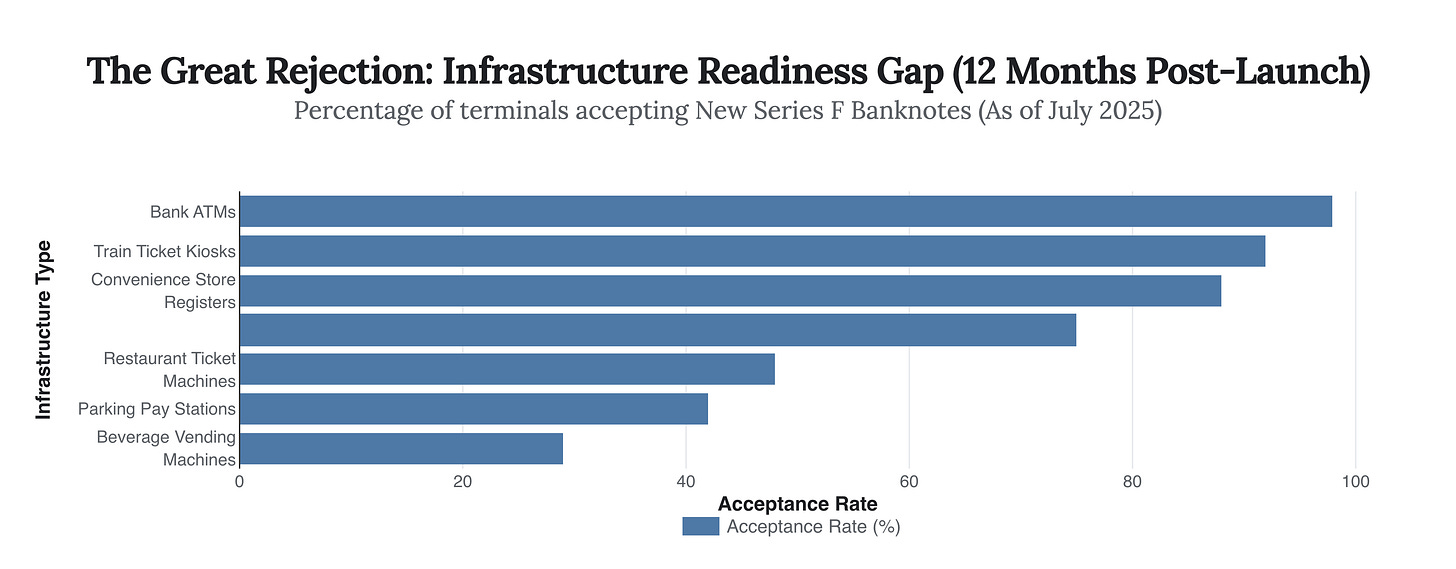

The core miscalculation of the 2024 rollout was the assumption of seamless infrastructure compatibility. In a hyper-automated society like Japan, cash is not merely a medium of exchange; it is a hardware dependency. The cost to update the nation’s payment terminals to recognize the new 3D holograms and magnetic patterns was estimated at ¥1.6 trillion ($10.3 billion). For a corporate giant like JR East, upgrading ticket gates is a rounding error. For a low-margin ramen shop or an independent vending machine operator, it is an existential crisis.

The Vending Machine Apocalypse

Japan’s density of vending machines is the highest in the world, but this asset turned into a liability the moment the new notes dropped. By mid-2025, industry data confirmed that nearly 70% of beverage vending machines still rejected the new currency. The economics of the upgrade—costing between ¥20,000 and ¥1 million per unit—simply do not pencil out for machines generating minimal daily profit. The result is a bifurcated liquidity map: the new money works in the glistening hubs of Tokyo, but becomes useless paper in the arteries of the local economy.

This hardware gap has created a phenomenon I call “Modification Insolvency.” Small business owners, already battered by rising wheat and energy prices, are choosing to close their doors rather than invest the ¥2 million required to upgrade their ticket machines. We are seeing a record spike in closures among the “1,000-yen barrier” shops—businesses that rely on high volume and low prices, and for whom a capital expenditure of this magnitude is impossible to recoup.

The Velocity Trap: The Hoard That Didn’t Move

The unspoken strategic goal of the redesign was to break the inertia of tansu yokin. The logic was sound: if you change the notes, grandmothers and cash-hoarders will feel compelled to bring their old bills to the bank, where they can be taxed, tracked, or invested. This would theoretically spike the velocity of money and support the BOJ’s inflationary goals.

The Reverse Effect

However, the friction described above has inverted the outcome. Because the old notes are still universally accepted while the new notes are frequently rejected by machines, the old currency has actually gained a “utility premium.” Rather than rushing to exchange old notes, the cash-reliant public is holding onto them. The new notes are circulating sluggishly, creating a liquidity trap where the physical medium of exchange is becoming less liquid than the digital alternative.

The chart above is the smoking gun of policy failure. The 2004 rollout saw rapid adoption because the ecosystem was ready. The 2025 stagnation signals that the friction of the physical economy is overpowering the central bank’s distribution channels. The ¥60 trillion hoard remains largely undisturbed, sleeping under mattresses, insulated from the economy.

The Digital Ultimatum: Inflation via Obsolescence

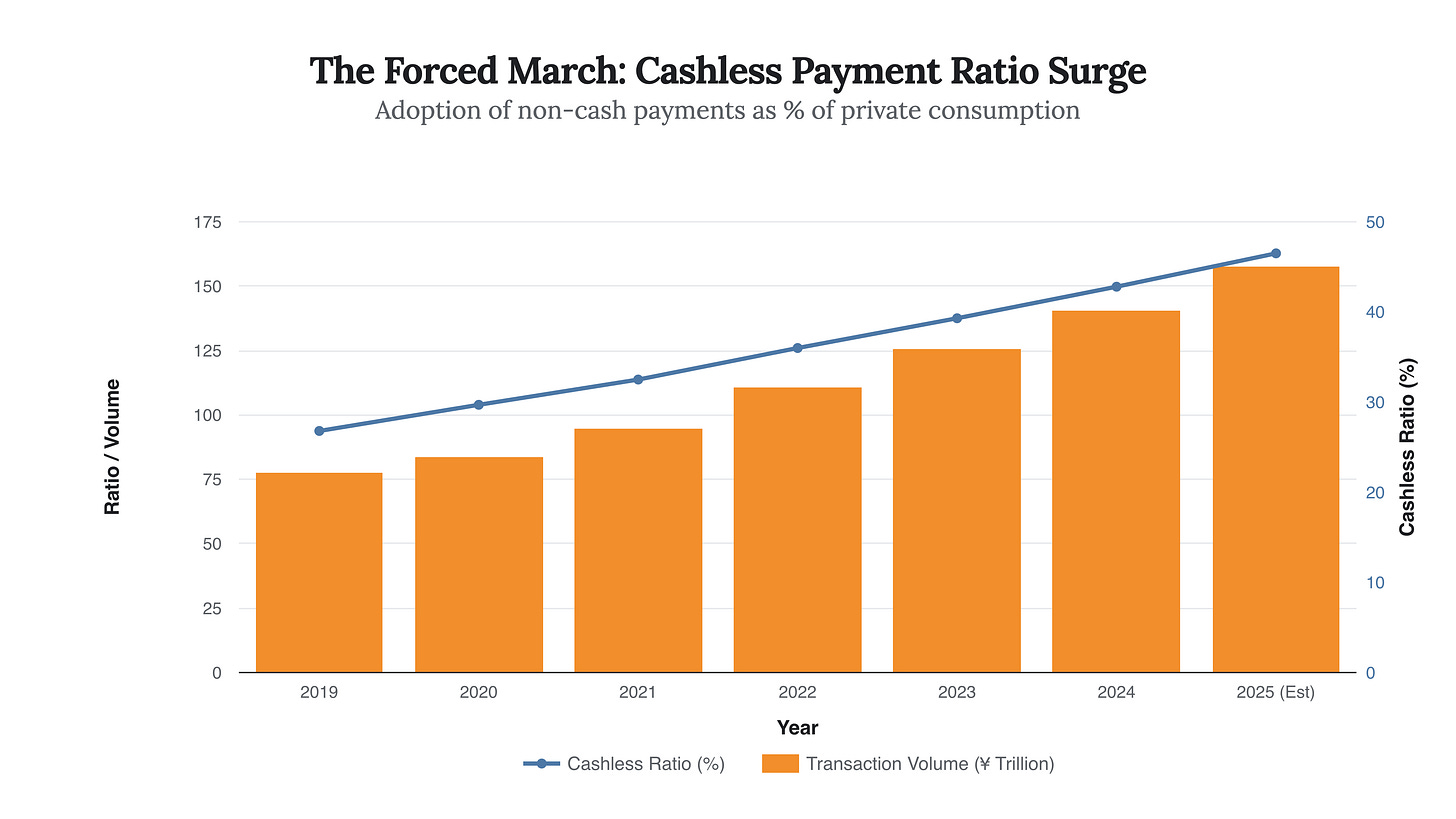

While the physical transition flails, the digital transition is ruthlessly efficient. The government’s push for a cashless society—targeting 80% adoption—has received an unintended boost from the currency debacle. Consumers, frustrated by vending machines that spit back their new ¥1,000 bills, are finally switching to QR code payments (PayPay, Rakuten Pay) and IC cards out of necessity, not preference.

Structural Inflation

This shift is inflationary. Cashless transactions carry merchant fees (typically 3.25%), which small vendors previously avoided. As shops upgrade their machines or switch to tablet-based cashless systems to bypass the banknote issue, they are passing these CapEx and OpEx costs to the consumer. This is contributing to the “sticky” service inflation we are observing in the CPI data. The ¥1,000 lunch is becoming the ¥1,200 lunch, not just because of ingredients, but because the mechanism of payment itself has become more expensive.

The data indicates that the currency redesign has acted as a massive subsidy for the fintech sector at the expense of the traditional cash infrastructure. We are witnessing the “platform-ization” of the Japanese Yen, where money is no longer a public good provided by the state, but a service provided by a payment processor.

Strategic Foresight: The Bifurcation of the Yen

Looking ahead to 2026, we must prepare for a bifurcated economy. The “Old Yen” will continue to circulate in rural areas and among the elderly, trading at a premium of convenience in the analog economy. The “New Yen” will serve as the bridge to a fully digital sovereign currency.

“The cost of money is no longer just interest rates. It is the cost of the hardware required to accept it. We are seeing a ‘hardware spread’ open up in the Japanese economy.”

Predictions for the next 12 months:

The “Vending Desert”: Expect a 15-20% reduction in the total number of vending machines in Japan by the end of 2026. Operators will liquidate unprofitable locations rather than upgrade them, altering the retail landscape of suburban Japan.

SME Consolidation: The bankruptcy wave in the hospitality sector will accelerate. Private equity will step in to roll up distressed “cash-only” chains, modernize their payment stacks, and raise prices.

Policy Pivot: The BOJ may be forced to incentivize the return of old notes more aggressively, perhaps by imposing fees on large-volume deposits of old currency, effectively taxing the hoard to force it into motion.

The final chart illustrates the human cost of this transition. The sharp uptick in bankruptcies in 2024 and 2025 is not solely due to food inflation—it is the “Modification Shock.” The businesses failing today are the ones that could not cross the digital divide imposed by the new banknotes.

Conclusion

The 2024 yen redesign serves as a potent reminder that in a complex economy, friction is cumulative. By underestimating the hardware dependencies of the Japanese economy, policymakers have triggered a painful cleansing of the SME sector. The intended inflation of demand has been replaced by an inflation of cost, and the intended velocity of money has been stalled by the very machines meant to facilitate it.

The strategic takeaway is clear: The new banknotes are not a stimulus; they are a filter, ruthlessly separating the businesses that can afford to digitize from those that cannot.