The $318 Billion Gap: Why the Math Behind the Trump ‘Tariff Dividend’ Is Impossible

A deep dive into the fiscal reality of the proposed $2,000 consumer rebate and the hidden liquidity crisis it ignores

The headline was tailored for maximum political impact: a $2,000 “tariff dividend” check for every low- and middle-income American, funded entirely by levies on foreign imports. It is a proposal that marries populist appeal with protectionist trade policy, promising to redistribute the spoils of a trade war directly into the pockets of the working class. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has tentatively endorsed the framework, suggesting checks could arrive by mid-2026. But beneath the surface of this proposal lies a chaotic collision of fiscal impossibilities, legal jeopardy, and second-order economic shocks.

Our analysis of the latest Treasury data and independent projections reveals a stark reality: the numbers do not add up. The gap between projected tariff revenue and the cost of the proposed rebate creates a fiscal hole exceeding $300 billion—a deficit that would likely be funded not by China, but by additional U.S. debt. Furthermore, while the public focuses on the $2,000 check, sophisticated operators are navigating a far more complex “rebate” landscape involving duty drawbacks, IEEPA litigation, and a potential Supreme Court ruling that could force the administration to refund billions to corporations rather than consumers.

The Arithmetic of Illusion: Revenue vs. Reality

The central premise of the rebate proposal is that foreign exporters will pay a premium for access to the U.S. market, generating a surplus large enough to subsidize domestic consumption. However, 2025 fiscal data paints a different picture. While tariff revenues have surged by over 150% compared to the pre-escalation baseline, they remain a fraction of the funding required to execute a universal or near-universal cash transfer.

The Funding Gap

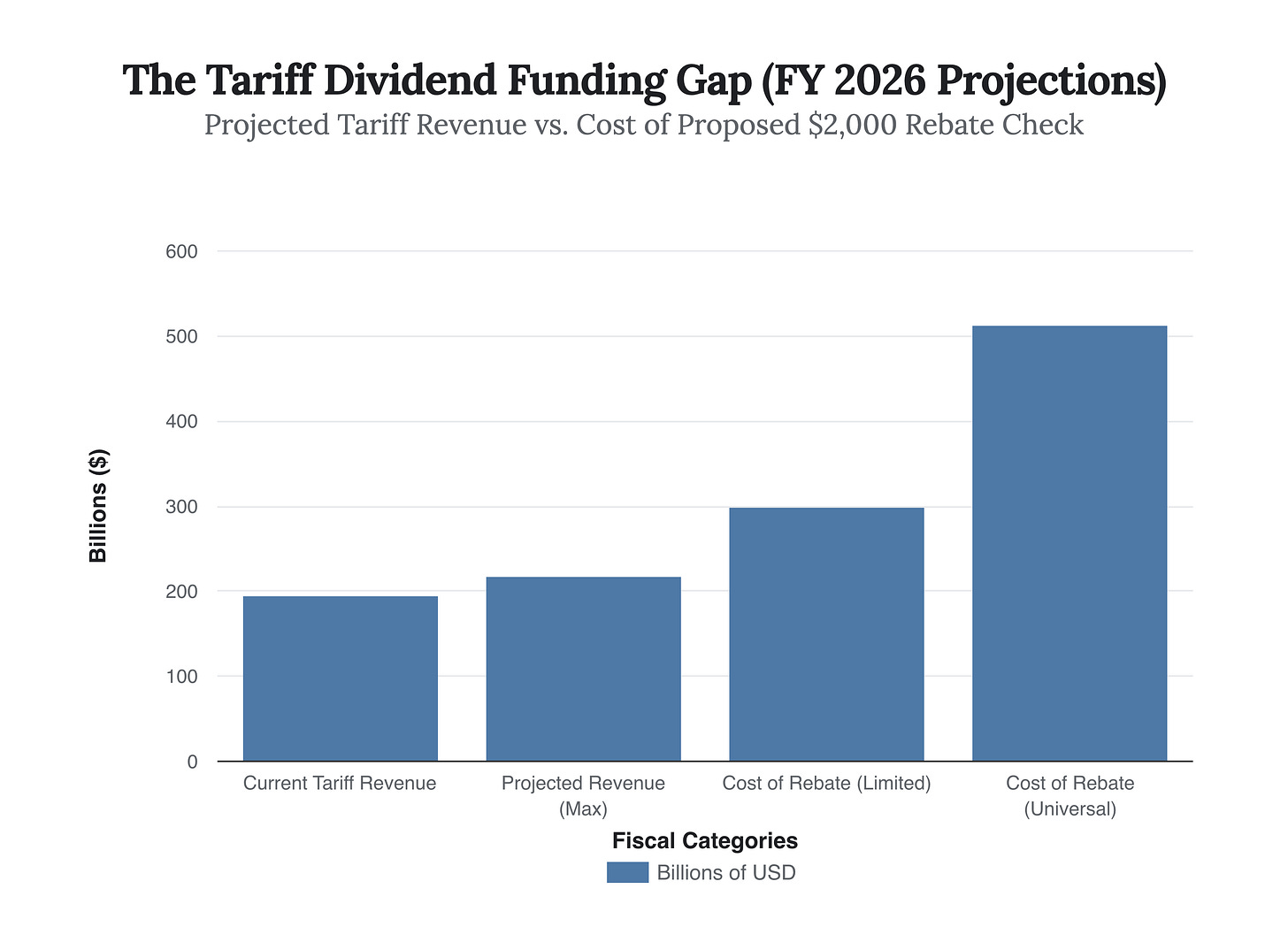

According to the Yale Budget Lab and recent Treasury statements, the new tariff regime—including the 10% universal baseline and 60% levy on Chinese goods—generated approximately $195 billion in customs duties in FY 2025. While substantial, this pales in comparison to the cost of the proposed dividend. A $2,000 check distributed to the estimated 150 million eligible adults (capped at $100,000 income) would cost the federal government roughly $300 billion. If the program is expanded to include dependents or higher income brackets, as some populists in the administration have urged, the cost balloons to nearly $600 billion.

The chart above visualizes this structural deficit. Even under the most optimistic revenue modeling—assuming no decline in import volumes—the administration faces a shortfall of at least $83 billion, and potentially as much as $318 billion. This “dividend” is effectively a debt-financed stimulus wrapped in protectionist branding.

The Inflationary offset: The ‘Net’ Benefit Analysis

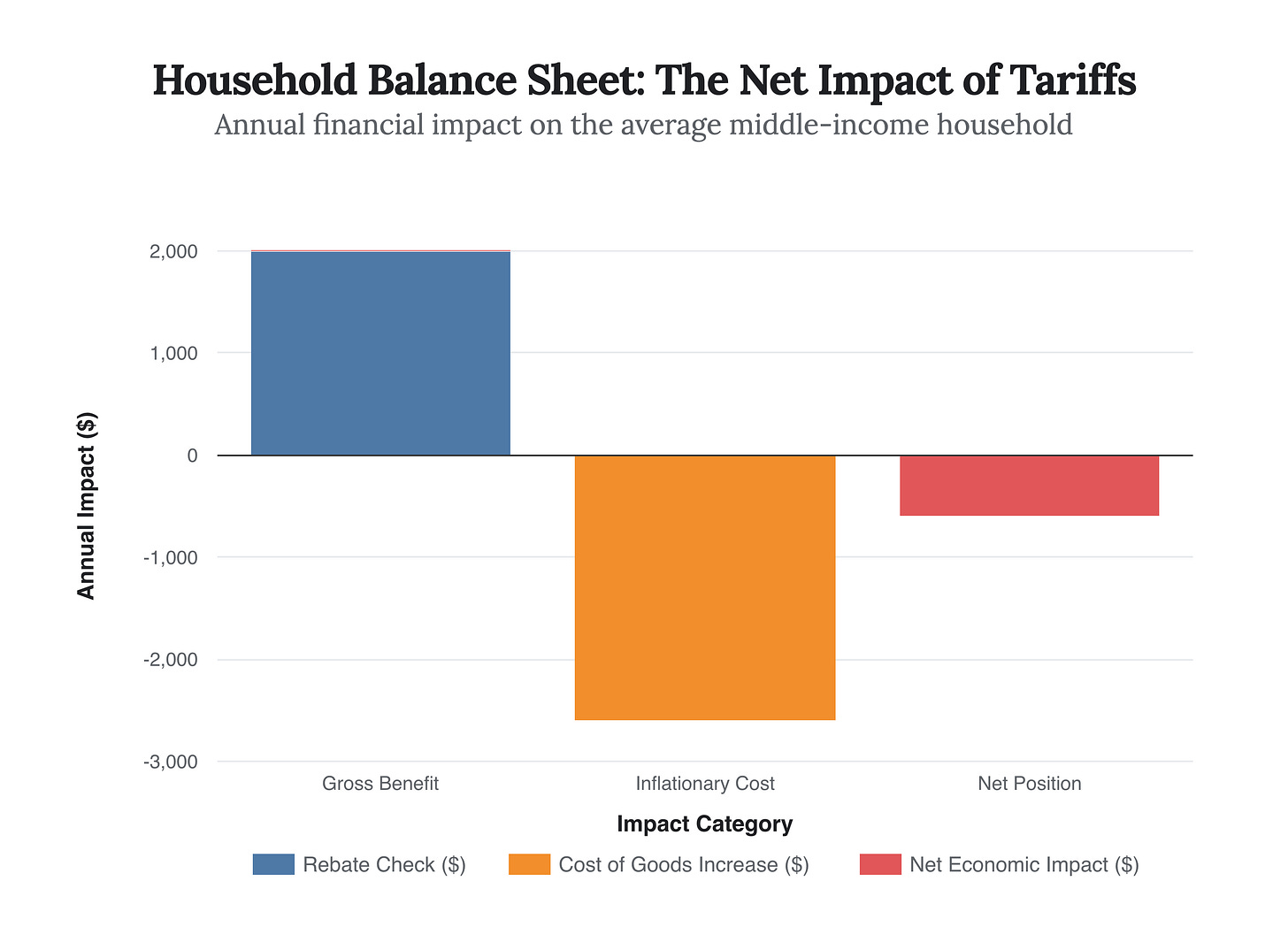

For the strategic investor, the critical metric is not the gross value of the check, but the net impact on household discretionary income. Tariffs are consumption taxes. While the legal incidence falls on the importer, the economic incidence—the actual cost burden—is almost invariably passed to the consumer through higher prices.

The $2,600 Hidden Tax

Data from the Tax Foundation and the Peterson Institute indicates that the new tariff schedule (10% universal, 60% China) will increase the average annual cost of goods for a U.S. household by approximately $2,600. When weighed against a one-time $2,000 rebate, the average household is left with a net deficit of $600 in purchasing power. This erodes the very demand the stimulus is intended to support.

This negative sum game suggests that the rebate is less of a dividend and more of a partial reimbursement for policy-induced inflation. Sectors heavily reliant on imported intermediate goods—such as consumer electronics, auto parts, and apparel—will see price elasticity tested as they pass these costs downstream.

The Corporate Maneuver: Duty Drawback & The ‘Reciprocal’ Loophole

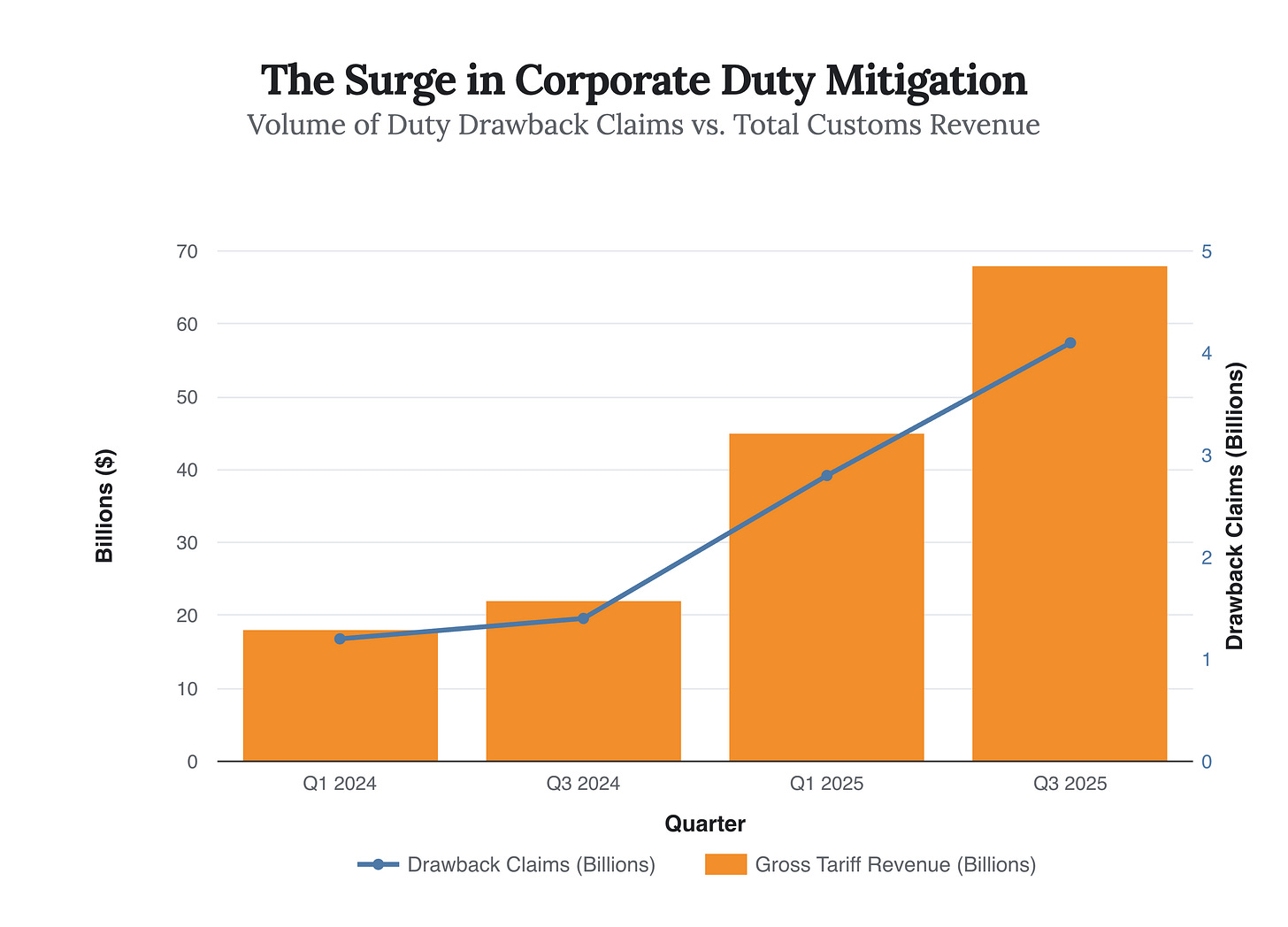

While the media fixates on the consumer check, a more sophisticated game is being played at the corporate level. The “Reciprocal Trade Act” framework allows for what is essentially a corporate rebate mechanism known as “duty drawback.” Companies that import taxed components but export the finished product can claim a refund of up to 99% of the duties paid.

Crucially, the administration has confirmed that drawback is available for the new 10% reciprocal tariffs, though explicitly forbidden for the 25% “fentanyl-related” tariffs on Mexico and Canada. This creates a bifurcated market where savvy supply chain operators can effectively neutralize the tariff regime, while domestic-only producers bear the full cost.

The sharp rise in drawback claims indicates that multinational corporations are rapidly adapting their logistics to arbitrage the U.S. tax code. The losers in this scenario are small-to-mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) lacking the administrative capacity to manage complex drawback filings or the global footprint to re-route exports.

The Black Swan: Learning Resources v. Trump

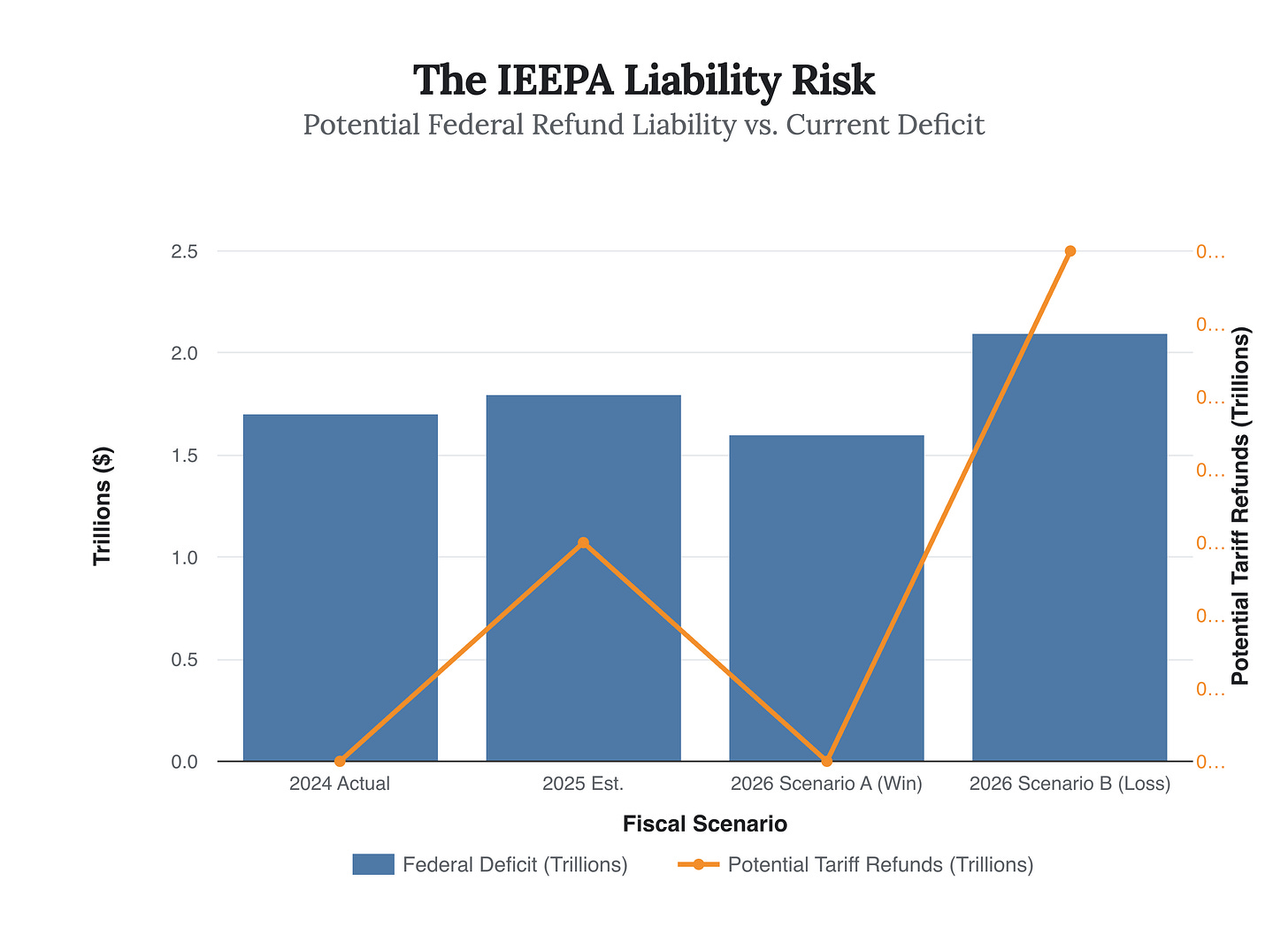

Perhaps the greatest threat to the rebate proposal is legal, not economic. The Supreme Court is currently weighing Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump, a case challenging the executive branch’s authority to use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to levy tariffs without Congressional approval.

If the Court rules against the administration, the consequences would be catastrophic for the “dividend” plan. Not only would the revenue stream evaporate overnight, but the Treasury could be legally obligated to refund billions in historically collected tariffs to importers. In this scenario, the “rebate” goes to Walmart and Target, not the American voter.

“If the court strikes down the tariffs, the Trump administration may have to refund the tariffs to importers, making dividend checks to American families no longer even a possibility.” — Scott Bessent, U.S. Treasury Secretary

Global Asymmetries and Market Signals

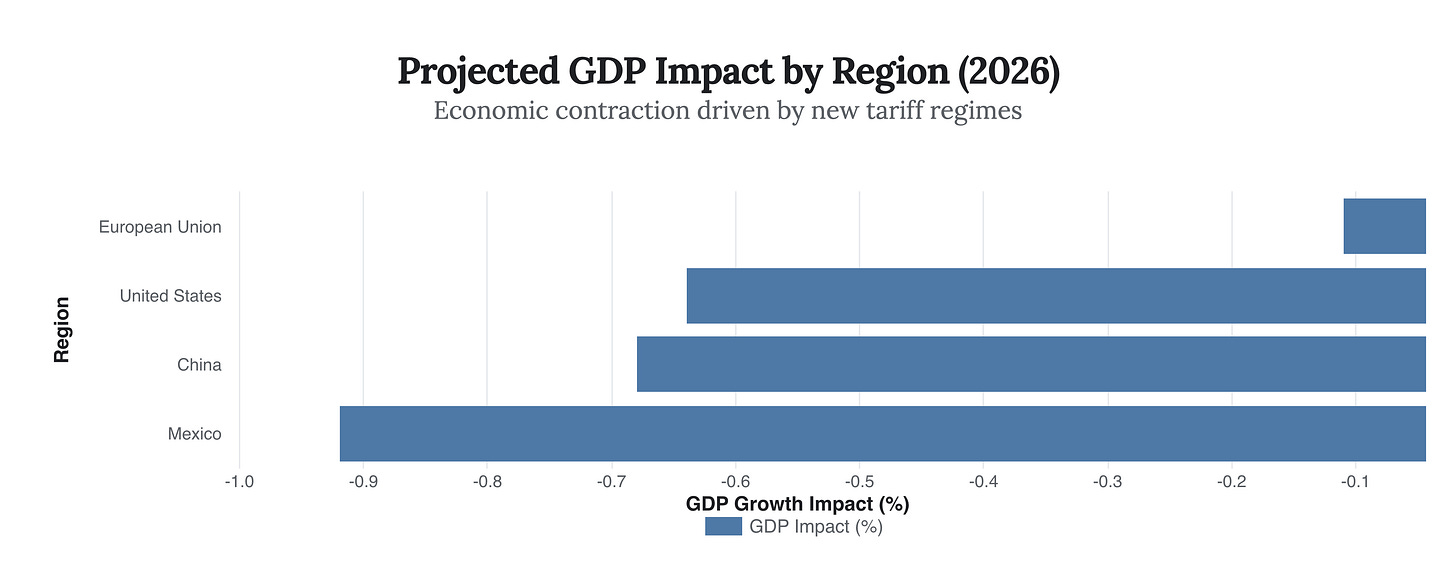

The rebate proposal effectively attempts to insulate the U.S. consumer from the global consequences of a trade war. However, the impact is unevenly distributed. While the U.S. GDP is projected to contract by roughly 0.64% due to these measures, China faces a slightly deeper contraction of 0.68%. The EU, by contrast, is relatively insulated (-0.11%). This asymmetry suggests that while the “check” is a domestic political tool, the tariff policy itself is a blunt geopolitical weapon designed to decouple the U.S. from Chinese manufacturing, regardless of the cost to the American consumer.

Conclusion: The Liquidity Mirage

The Trump tariff rebate proposal is a masterclass in political misdirection. It frames a complex, inflationary trade shock as a direct cash transfer to the working class. However, the data is unequivocal: the revenue is insufficient, the net economic impact on households is negative, and the legal foundation is crumbling.

For investors, the signal is clear: do not bet on a consumer spending boom driven by these checks. Instead, focus on the corporate adaptation layer—logistics firms, customs brokers, and multinationals with the sophistication to utilize duty drawback mechanisms. These are the entities that will actually capture the value of the “rebate,” while the average consumer pays the invoice.

The true strategic insight is that the administration is financing a trade war with a credit card, promising to pay the bill with a rebate check that may never clear.