The £3 Billion Trade-Off: The UK Just Accepted a 25% Drug Price Hike

Behind the new zero-tariff agreement lies a costly gamble for the NHS

In a move that redefines the economics of the profound “Special Relationship,” the United Kingdom and the United States have struck a landmark zero-tariff agreement on medicines this week. Announced on Monday and solidified today, the deal secures a critical lifeline for Britain’s £11.1 billion pharmaceutical export industry. But this market access comes with a staggering domestic price tag: a commitment by the NHS to pay 25% more for innovative American drugs.

As the dust settles on the announcement from the Trump administration and Downing Street, the contours of the deal reveal a stark transactional reality. To shield its life sciences sector from the looming threat of protectionist tariffs—which have already hit European competitors—the UK has effectively agreed to subsidize its export success with its own healthcare budget. The agreement is not just a trade deal; it is a structural shift in how Britain values, pays for, and accesses medical innovation.

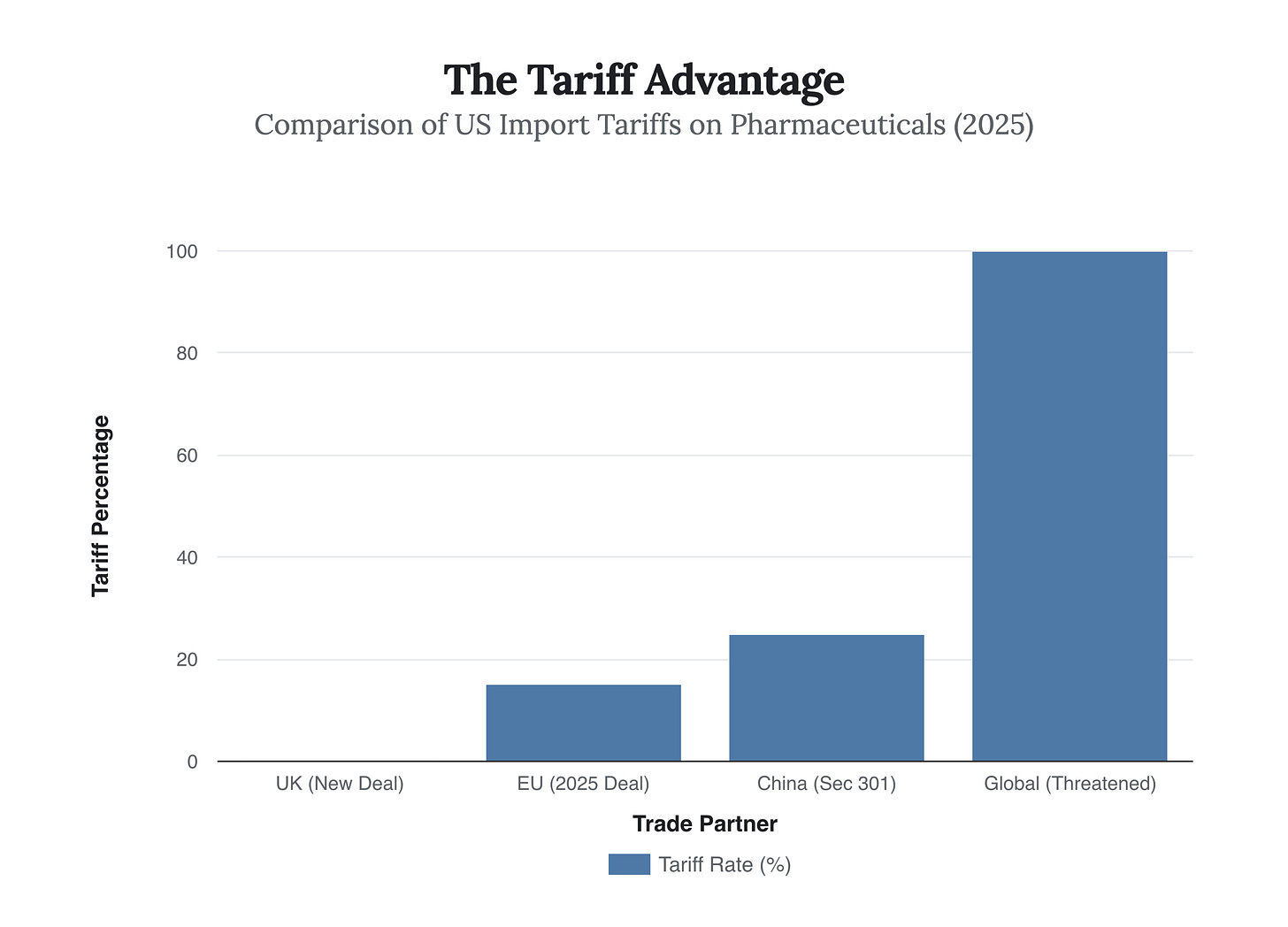

The chart above illustrates the immediate strategic victory for the UK. While the European Union recently acquiesced to a 15% tariff on its pharmaceutical exports to the US, Britain stands alone with a 0% rate. In the context of President Trump’s threatened 100% levies on foreign drugs, this exemption is an existential win for companies like AstraZeneca and GSK, who have substantial manufacturing footprints in the UK. Without this shield, the cost of doing business across the Atlantic would have become prohibitive, likely forcing a manufacturing exodus to American soil.

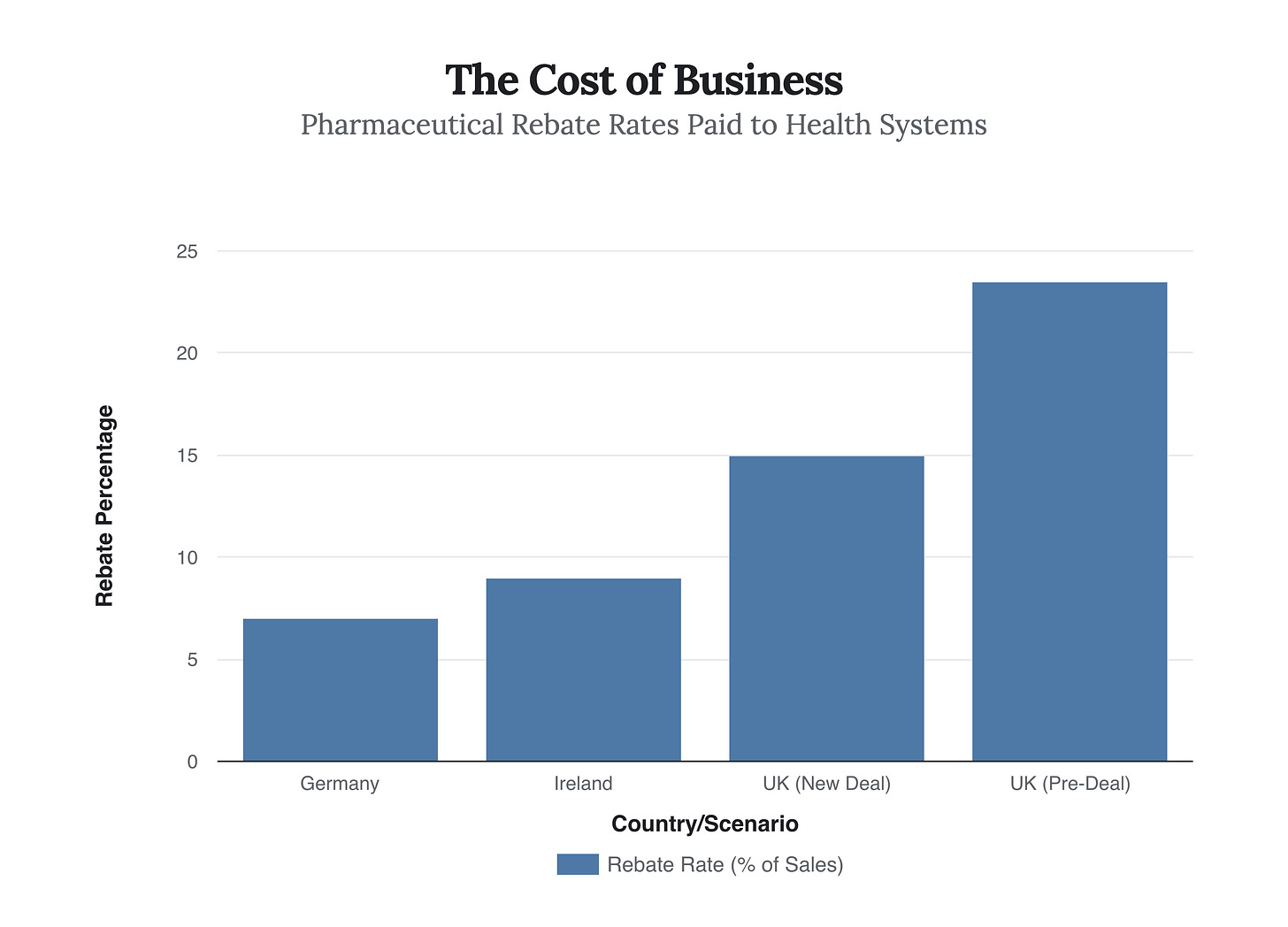

However, the concession required to secure this exemption is equally dramatic. For decades, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has been the world’s toughest negotiator, using strict cost-benefit analyses to drive down drug prices. That era appears to be ending. Under the new terms, the UK has agreed to a “voluntary” rebate cap reduction and a net price increase for new medicines.

As shown in the comparison above, the UK is slashing the rebate rate—the money drug companies must pay back to the NHS if they exceed sales caps—from nearly 24% to just 15%. This aligns the UK more closely with other business-friendly European markets like Ireland and Germany, but it represents a direct loss of revenue for the NHS. Combined with the agreement to pay 25% higher net prices for new therapies, the total additional cost to the UK taxpayer is estimated at £3 billion annually.

“This vital deal will ensure UK patients get the cutting-edge medicines they need sooner, and our world-leading UK firms keep developing the treatments that can change lives.” — Liz Kendall, UK Science and Technology Secretary

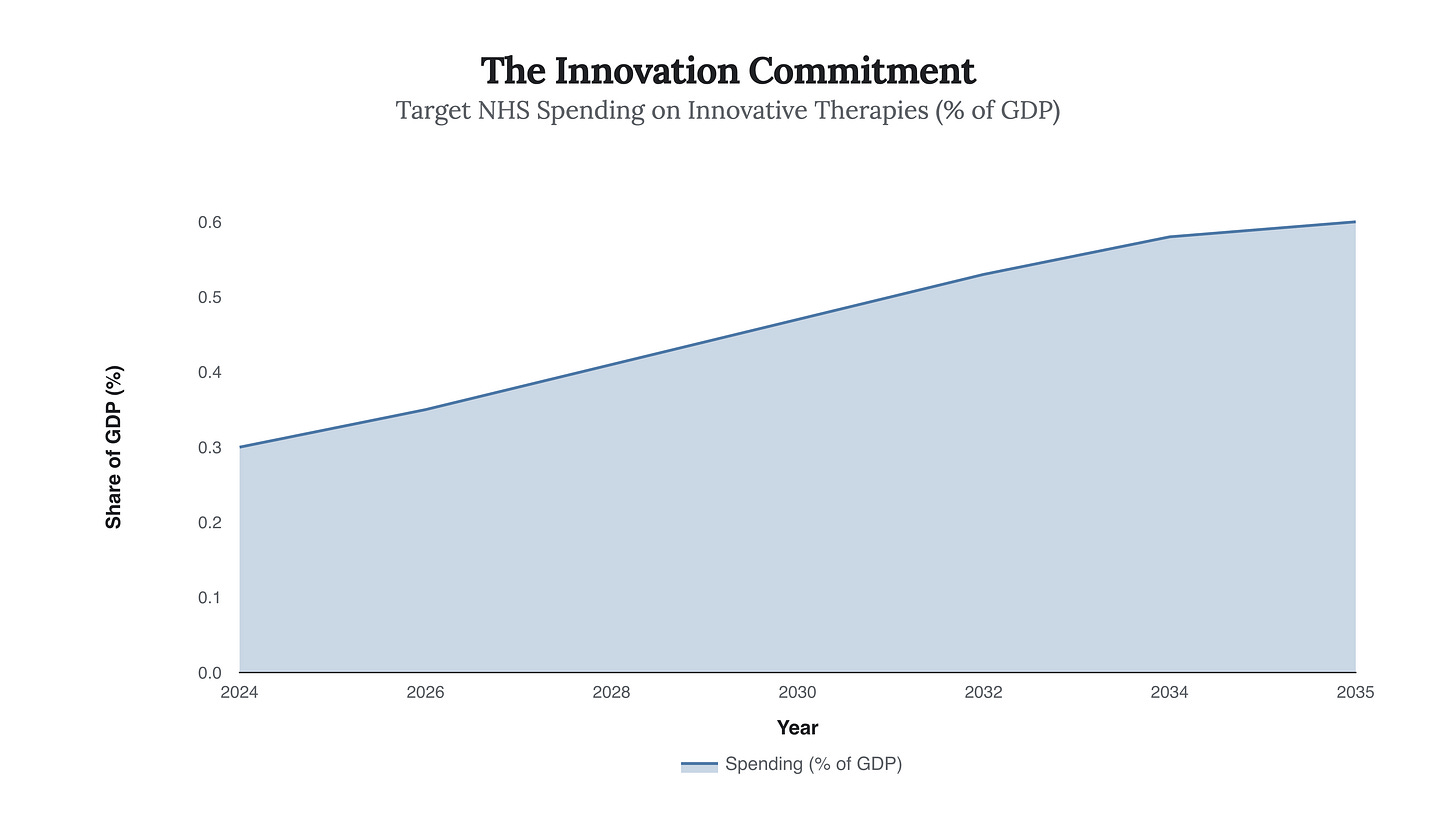

The government frames this as an investment in modernization. By agreeing to double its spending on innovative therapies as a percentage of GDP over the next decade, the UK is attempting to transform the NHS from a budget-conscious purchaser into a driver of global innovation.

The logic is that by paying more, the UK becomes a priority launch market for new treatments, reversing the recent trend where companies have prioritized the US and Europe over Britain.

This projected doubling of investment, from 0.3% to 0.6% of GDP, creates a guaranteed revenue stream for pharmaceutical giants. It effectively locks the NHS into a long-term stimulus plan for the industry. While this secures the supply chain and protects the 17.4% of UK goods exports that come from the sector, it fundamentally alters the social contract of the NHS.

“This agreement... strengthens the global environment for innovative medicines and brings long-overdue balance to US–UK pharmaceutical trade.” — Robert F. Kennedy Jr., US Health Secretary

Ultimately, the zero-tariff deal is a pragmatic recognition of Britain’s post-Brexit economic reality. Lacking the collective bargaining power of the EU, the UK has chosen to trade fiscal efficiency for industrial security. The winners are the exporters and arguably the patients who will see faster access to new drugs; the silent partner paying the bill is the British taxpayer, who has just signed a £3 billion annual subscription to the world’s most advanced medicine cabinet.