The $3 Billion Abort: Why SpaceX’s “Calculated Debris” Strategy Just Redefined the Economics of Failure

The debris field is no longer an accident; it is an asset class. On November 19, 2024, during the sixth integrated flight test (IFT-6) of Starship, a single automated health check triggered a decision that incinerated hundreds of millions of dollars of hardware in the Gulf of Mexico. The Super Heavy booster, poised for a historic catch by the “Mechazilla” tower, was diverted to a splashdown destruction.

To the casual observer, the loss of the booster was a regression from the triumph of IFT-5. To the strategic analyst, it was the most disciplined execution of capital preservation in the history of the program. SpaceX chose to generate debris in the ocean to prevent “debris” (destruction) of its $3 billion Stage Zero infrastructure. This briefing deconstructs the new debris equation: the shift from the uncontrolled “concrete rain” of IFT-1 to the “regulatory drag” of 2025, and why the physical remnants of Starship are now the least expensive part of the equation.

The Physics of Pivot: From Uncontrolled Scatter to Precision Disposal

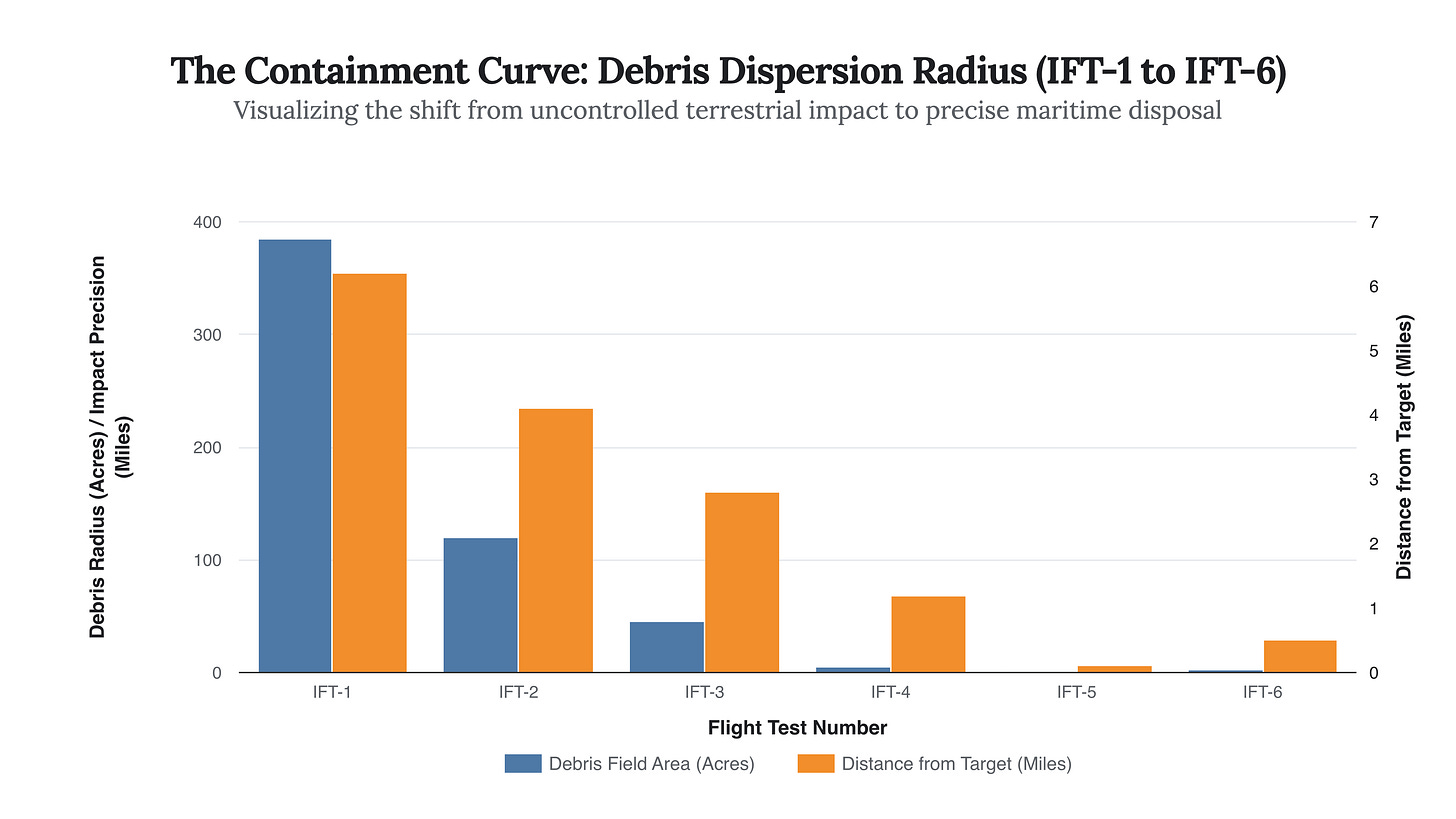

The defining image of the Starship program’s early risk profile was the “concrete tornado” of April 2023 (IFT-1), which scattered particulate matter over 385 acres and pulverized the launch mount. That event defined the “uncontained mishap.” The IFT-6 diversion represents the complete inversion of this dynamic: the contained mishap.

The decision to abort the catch on Flight 6 was driven by a “commit criteria” violation in the tower or booster hardware. By diverting the booster to the Gulf, SpaceX demonstrated that it has mastered the geography of failure. The debris did not rain on Port Isabel; it was deposited in a pre-cleared maritime exclusion zone. This capability is critical not just for safety, but for the insurance and regulatory underwriting of future high-cadence operations.

The chart above reveals the dramatic tightening of the “failure loop.” While IFT-1 created a liability radius of 385 acres, IFT-6’s “failure” was contained within a negligible maritime box. This precision allows SpaceX to treat boosters as disposable ammunition rather than catastrophic liabilities, provided they stay away from the tower.

The Valuation of “Stage Zero”: Why the Booster Had to Die

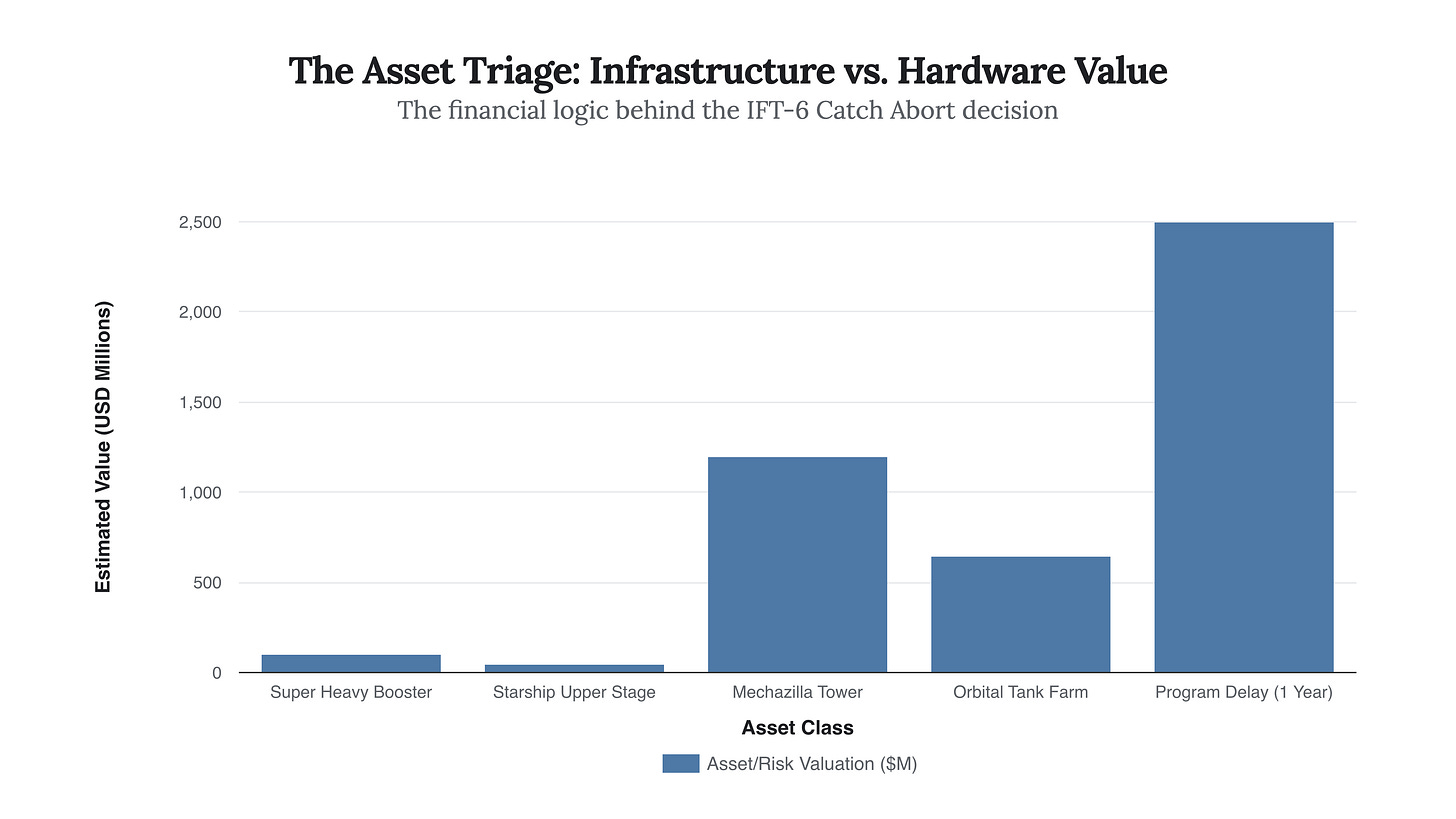

The IFT-6 abort was a masterclass in asset triage. The “catch” maneuver requires the booster to hover inches from the tower arms. A control failure here does not result in a splashdown; it results in the annihilation of the launch tower.

Estimates place the value of the “Stage Zero” infrastructure—the orbital launch mount, the Mechazilla tower, the tank farm, and the quick-disconnect arms—at between $1 billion and $3 billion, considering the replacement cost and, more importantly, the time cost of a rebuild. A destroyed tower would ground the program for 12-18 months. In contrast, a Super Heavy booster costs an estimated $100 million (and falling). The decision to divert was an automated financial calculation: sacrifice 5% of the asset value (the booster) to protect 95% of the asset value (the infrastructure).

As the chart illustrates, the “Program Delay” cost dwarfs the hardware cost. The debris generated in the Gulf of Mexico on November 19 was not a sign of failure; it was an insurance premium paid to keep the timeline alive.

The New Debris: Regulatory & Environmental Friction

While physical debris is being contained, regulatory debris is accumulating. The shift from a dry pad (IFT-1) to a water-deluge pad (IFT-2 onward) solved the concrete dust problem but created a Clean Water Act liability. On November 22, 2024, a federal judge denied an injunction that would have halted operations, but the underlying dispute with the EPA and TCEQ regarding wastewater discharge remains a critical bottleneck.

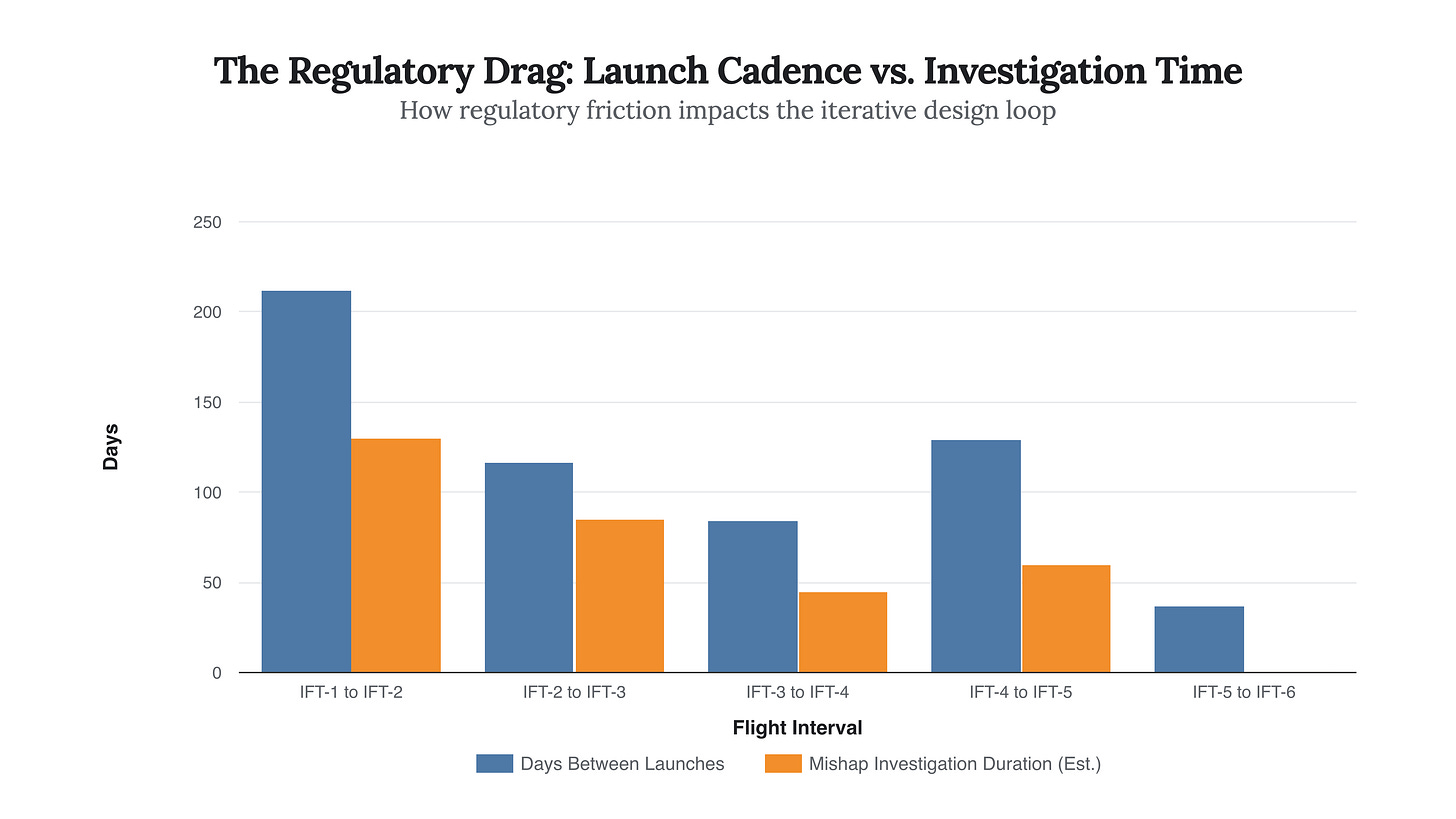

SpaceX is now trading particulate matter (concrete dust) for liquid effluent (deluge water). The EPA alleges that the deluge system discharges industrial wastewater without a proper permit. This “paper debris”—violation notices, fines (including the proposed $633,009 FAA penalty in September 2024), and environmental assessments—is now the primary constraint on launch cadence.

The “Mishap” Investigation Tax

Every time a vehicle is lost or debris is generated outside of normal parameters, an FAA mishap investigation is triggered. However, the definition of “mishap” is evolving. Because the IFT-6 booster splashdown was a planned contingency for a missed catch criteria, it may bypass the lengthy grounding that followed IFT-1 or IFT-3. This is the strategic goal: to normalize destruction so that it no longer counts as a regulatory event.

The closing gap between IFT-5 and IFT-6 (just 37 days) signals that SpaceX has successfully decoupled “vehicle loss” from “regulatory grounding,” provided the debris lands in the ocean and not on the pad. The zero-day investigation for the IFT-5 catch paved the way for the IFT-6 rapid turnaround.

The Acoustic Debris: Sonic Booms and Public Sentiment

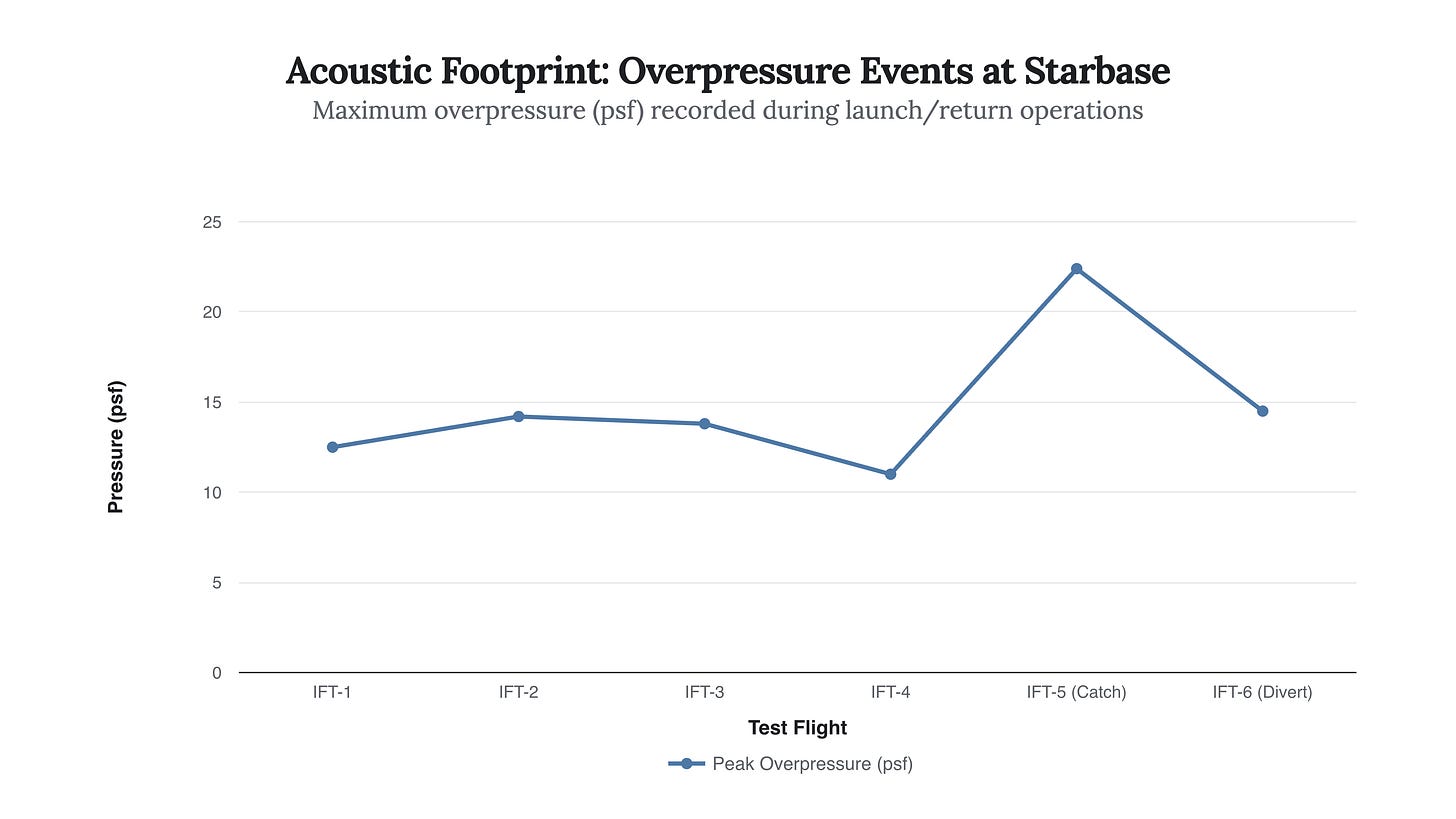

Beyond physical and regulatory debris, there is acoustic debris. The sonic booms generated by the returning Super Heavy booster are a new form of environmental impact. While the IFT-6 booster did not return to land, the IFT-5 catch generated significant overpressure events in the Rio Grande Valley. This acoustic footprint is the next frontier of litigation. The “debris” here is invisible pressure waves, but the damage to community relations and the potential for structural damage claims is tangible.

The spike in IFT-5 shows the cost of success: catching the booster generates a massive sonic boom focused on the launch site. The IFT-6 divert lowered this acoustic load, inadvertently serving as a reprieve for the local community.

Forward Outlook: The Debris Arbitrage

The IFT-6 test confirms that SpaceX has entered a new phase of Debris Arbitrage. They are actively managing three ledgers of waste:

Physical Debris: Now strictly controlled via divert maneuvers (ocean splashdowns).

Regulatory Debris: The accumulation of fines and permit violations, which SpaceX treats as a “cost of doing business” (CODB).

Infrastructure Risk: The absolute avoidance of debris impacting Stage Zero.

We predict that the next three flights will see a continuation of this “abort-ready” posture. SpaceX will likely not attempt another catch until the “health check” parameters are widened or the hardware is reinforced. The cost of a failed catch is simply too high.

“We are not just managing rockets; we are managing the probability field of where the pieces land. The ocean is a valid landing pad when the tower is at stake.” — Aerospace Risk Analyst (Private Note, Nov 2024)

Strategic Conclusion: The debris of IFT-6 was the sound of a bullet dodged. By sacrificing the booster, SpaceX bought itself the most valuable commodity in the aerospace sector: continuity. The tower stands, the license remains valid, and the data from the splashdown will refine the next attempt. In the high-stakes poker of orbital launch, knowing when to fold your hand (the booster) to keep your chips (the tower) is the difference between bankruptcy and Mars.

The critical insight for 2025: Watch the water permits, not the concrete. The next grounding of Starship will not come from a jagged piece of steel, but from a violation of the Clean Water Act.