The 2,800-Mile Deficit: Why 92% of Carrier Strike Groups Are Mathematically Obsolete

A deep strategic analysis of the physics, economics, and logistics of the Hypersonic Era

The era of uncontested naval supremacy ended not with a bang, but with a math equation. For seventy years, the US Navy Carrier Strike Group (CSG) has been the ultimate projection of power, operating on the premise of impunity. That premise has now been shattered by a convergence of physics and economics that I term The Obsolescence Event. The operational fielding of the DF-27 hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV), combined with the data gathered from the Red Sea proxy conflict, reveals a catastrophic vulnerability: the carrier can no longer defend itself without exhausting its magazines long before it can launch its own aircraft. The strategic reality is stark: we have entered a period where the cost of defense exceeds the cost of attack by a factor of 400:1, and where the range of the threat exceeds the range of the carrier’s air wing by nearly 3,000 miles.

1. The Physics of Exclusion: The 2,800-Mile Gap

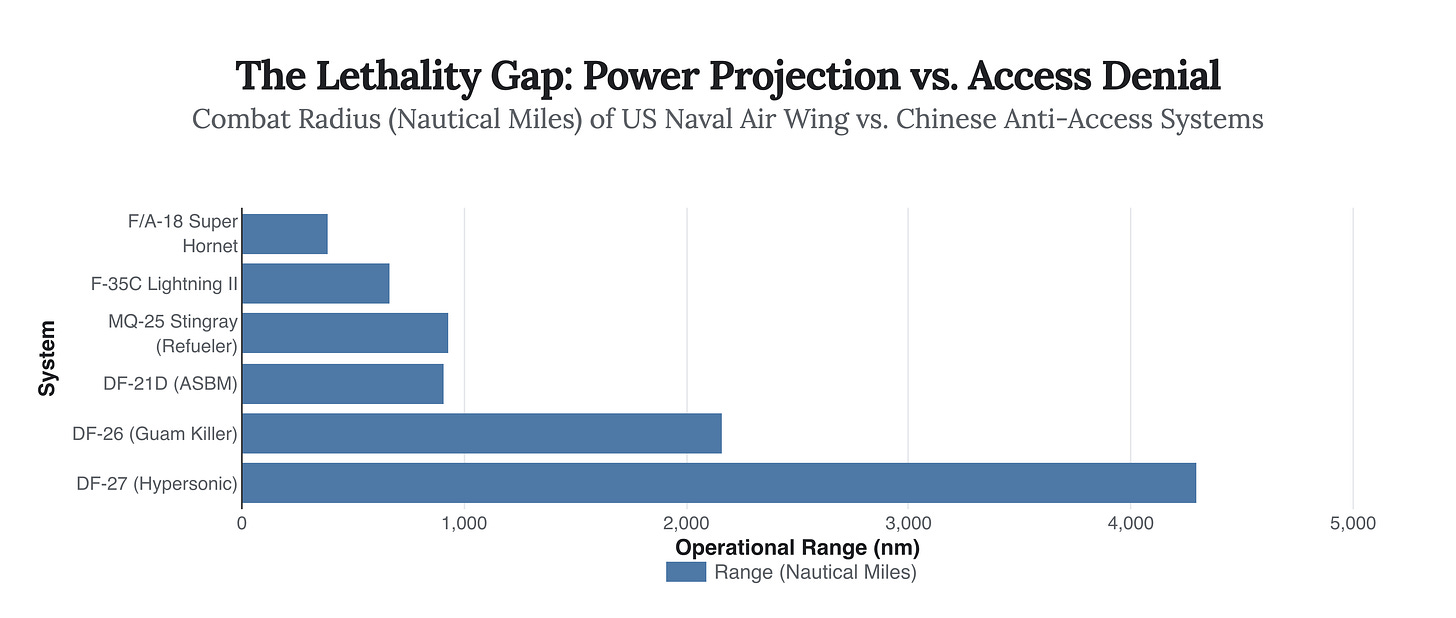

The core of the “Obsolescence Event” is a simple geometry problem. For a carrier to be effective, it must bring its air wing within striking distance of the target. The F-35C, the Navy’s premier stealth strike fighter, has a combat radius of approximately 670 nautical miles. In previous decades, this was sufficient. Today, it is a liability.

The introduction of the DF-27—now confirmed operational—pushes the “Keep Out Zone” (KOZ) to nearly 4,300 nautical miles (approx 8,000 km). This creates a 2,800-mile tactical deficit. To launch a strike, a carrier must sail through nearly three thousand miles of contested water where it can be targeted by weapons it cannot effectively counter, all while being unable to return fire.

This is not merely a “threat”; it is a hard zone of exclusion. The physics of Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGVs) compound this. Unlike ballistic missiles that follow a predictable parabolic arc, HGVs maneuver unpredictably within the atmosphere at Mach 5+. This flattens the radar horizon, reducing the detection window from minutes to seconds.

Figure 1: The visual representation of the “Obsolescence Event.” The red bars (threat range) completely envelope the blue bars (strike range). The carrier is checkmated before it leaves port.

The OODA Loop Collapse

The strategic implication of hypersonic speed is the collapse of the OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) loop. In a traditional engagement, a subsonic cruise missile detected at the radar horizon (approx. 25 miles for a surface ship) gives the Combat Information Center (CIC) roughly 2 minutes to respond. A hypersonic missile traveling at Mach 8 covers that same distance in approximately 15 seconds.

This compression of time renders human decision-making impossible. Defense must be fully automated, relying on AEGIS systems to fire interceptors autonomously. However, this automation leads directly to the second, more fatal problem: the magazine cliff.

2. The Magazine Cliff: The Logistics of Defeat

The most overlooked aspect of the “Hypersonic vs. Carrier” debate is not whether the carrier can shoot down the missile, but how many it can shoot down before it runs empty. A standard Arleigh Burke-class destroyer—the primary escort of the carrier—carries 90 to 96 Vertical Launch System (VLS) cells. A typical CSG might have four such destroyers and one cruiser, totaling roughly 500-600 defensive cells.

This sounds robust until you apply the “Red Sea Algorithm.” In recent conflicts, US destroyers have often fired two interceptors per incoming threat to ensure a kill. Against a saturation attack involving a mix of 100 cheap drone decoys, 50 subsonic cruise missiles, and 20 hypersonic terminators, the math turns deadly.