The 2.8 Million Withdrawal

Why Britain’s Real Labour Crisis Isn’t a Record Unemployment Rate, But a Record Exodus from the Workforce

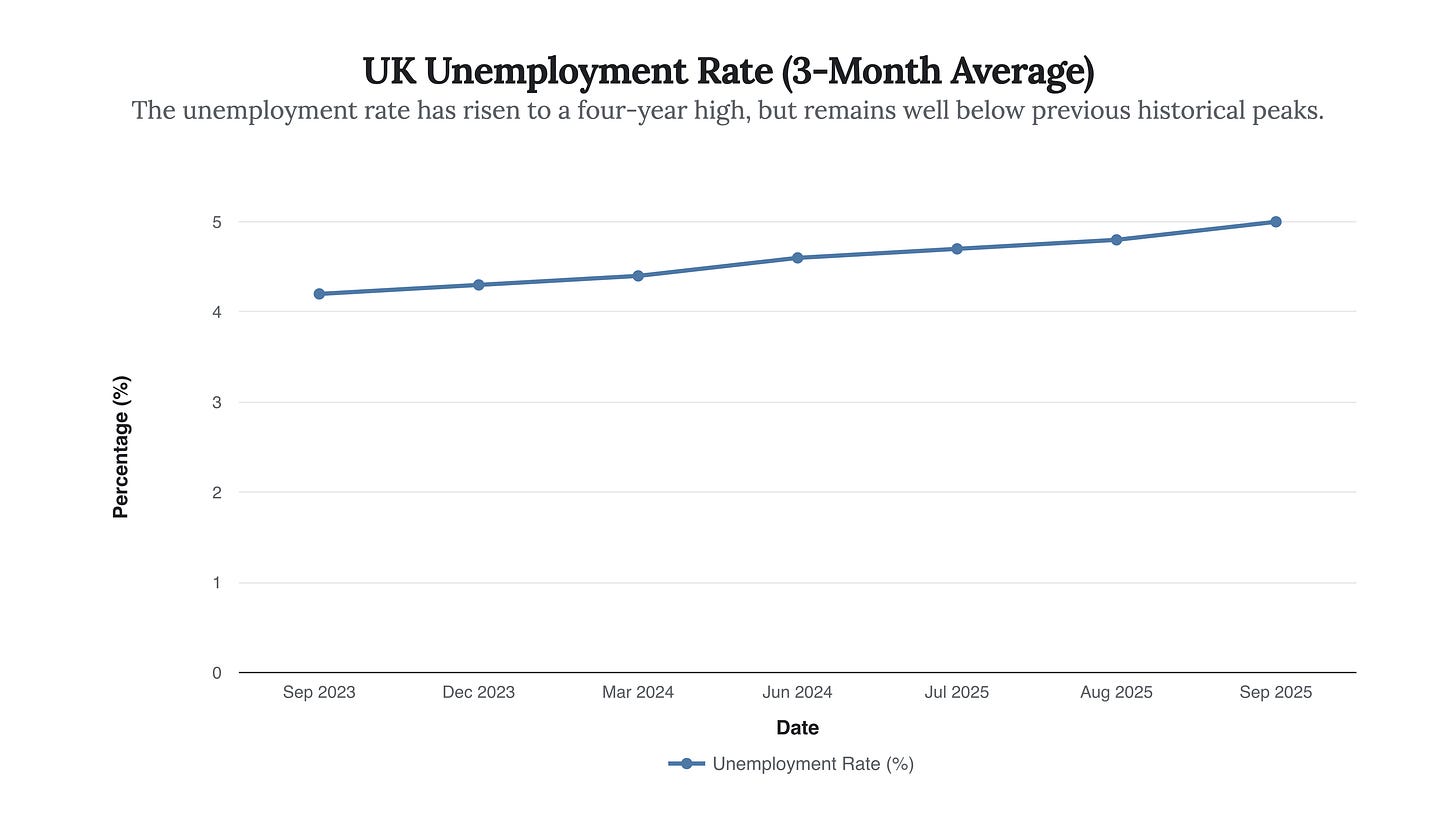

The United Kingdom’s latest labour market data presents a deceptive picture of stability teetering on the edge of decline. The headline unemployment rate, which rose to 5.0% in the three months to September 2025, marks a four-year high but falls conspicuously short of a historical record. For industry leaders, investors, and policymakers, focusing on this single metric is a critical strategic error. It masks a far more profound and intractable crisis: a structural collapse in workforce participation, driven by an unprecedented surge in long-term sickness. While the nation debates a 5.0% unemployment figure, a staggering record 2.8 million working-age people are now economically inactive due to ill health, an exodus that is quietly strangling economic potential.

This intelligence briefing deconstructs the official narrative to reveal the two-front war being waged on the UK’s labour supply. First, we will dissect the alarming rise in economic inactivity, a phenomenon that has made the UK a negative outlier among its G7 peers and poses a direct threat to long-term growth by shrinking the available talent pool. Second, we will analyze the acute and disproportionate crisis unfolding in youth employment, where joblessness is more than three times the national average and threatens to create a lost generation, permanently scarring the nation’s future productivity. This is not a cyclical downturn; it is a structural schism. The strategic challenge is no longer merely about job creation, but about addressing the deep-seated issues of public health and youth engagement that are actively eroding the workforce from within.

The Anatomy of a Deceptive Headline: Deconstructing the 5.0% Figure

The recent ascent of UK unemployment to 5.0% is a significant economic indicator, representing the highest level since the pandemic-induced shocks of early 2021. The increase, which surprised analysts who had forecast a slightly lower rate of 4.9%, has been driven by a tangible cooling in the labour market, with payroll numbers falling and job vacancies stabilizing after a prolonged decline. Yet, to label this a “record high” would be to ignore decades of economic history. The current rate pales in comparison to the peaks seen in previous recessions, such as the 11.9% recorded in 1984. This context is crucial; it shifts the focus from a cyclical jobs panic to a more nuanced analysis of the structural weaknesses the current environment is exposing.

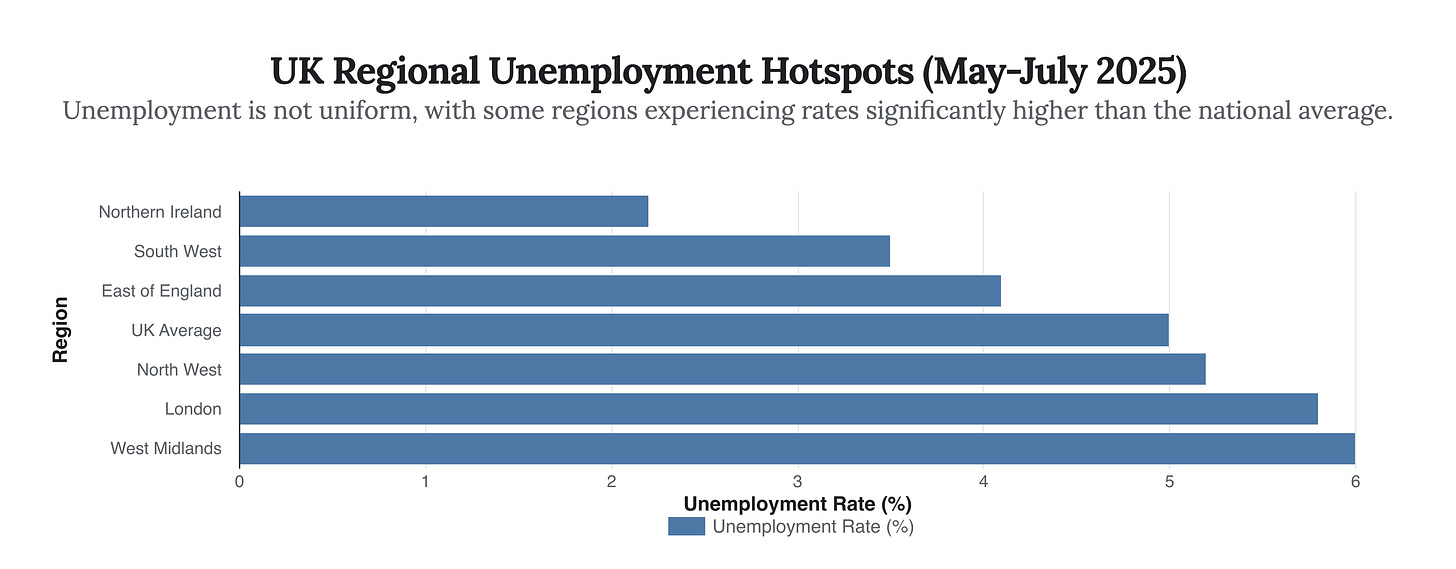

A granular look at the data reveals that the pain is not distributed evenly across the nation. The national average conceals significant regional disparities that point to deep-seated economic imbalances. As of mid-2025, regions like the West Midlands and London reported unemployment rates as high as 6.0% and 6.2% respectively, while Northern Ireland posted a rate of just 2.2%. In some urban centers, the situation is even more dire, with areas like Perry Barr in Birmingham reporting localized unemployment rates exceeding 15%. This fragmentation indicates that national-level policy responses may be insufficient, requiring targeted interventions to address localized de-industrialization, skills gaps, and infrastructure deficits.

The Cooling Market and Policy Implications

The weakening labour market is a direct result of slowing economic demand and rising costs for businesses. Employers, facing uncertainty ahead of the government’s November budget and grappling with the impact of increased National Insurance contributions, have scaled back hiring intentions. This slowdown in the private sector, coupled with slowing wage growth, is putting pressure on the Bank of England. Economists now suggest the cooling labour market strengthens the case for an interest rate cut in December to stimulate growth.

“Today’s official jobs statistics are a stark reminder to the Chancellor that she needs to back business to tackle the rising unemployment and redundancies caused by a year of weak growth and rising business costs. Only business can deliver the growth she needs to balance the books.”

- Neil Carberry, Chief Executive of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation (REC)

However, this focus on monetary policy and headline figures overlooks the more dangerous, supply-side undercurrent. The core problem is not just a temporary dip in demand for workers, but a shrinking supply of them.

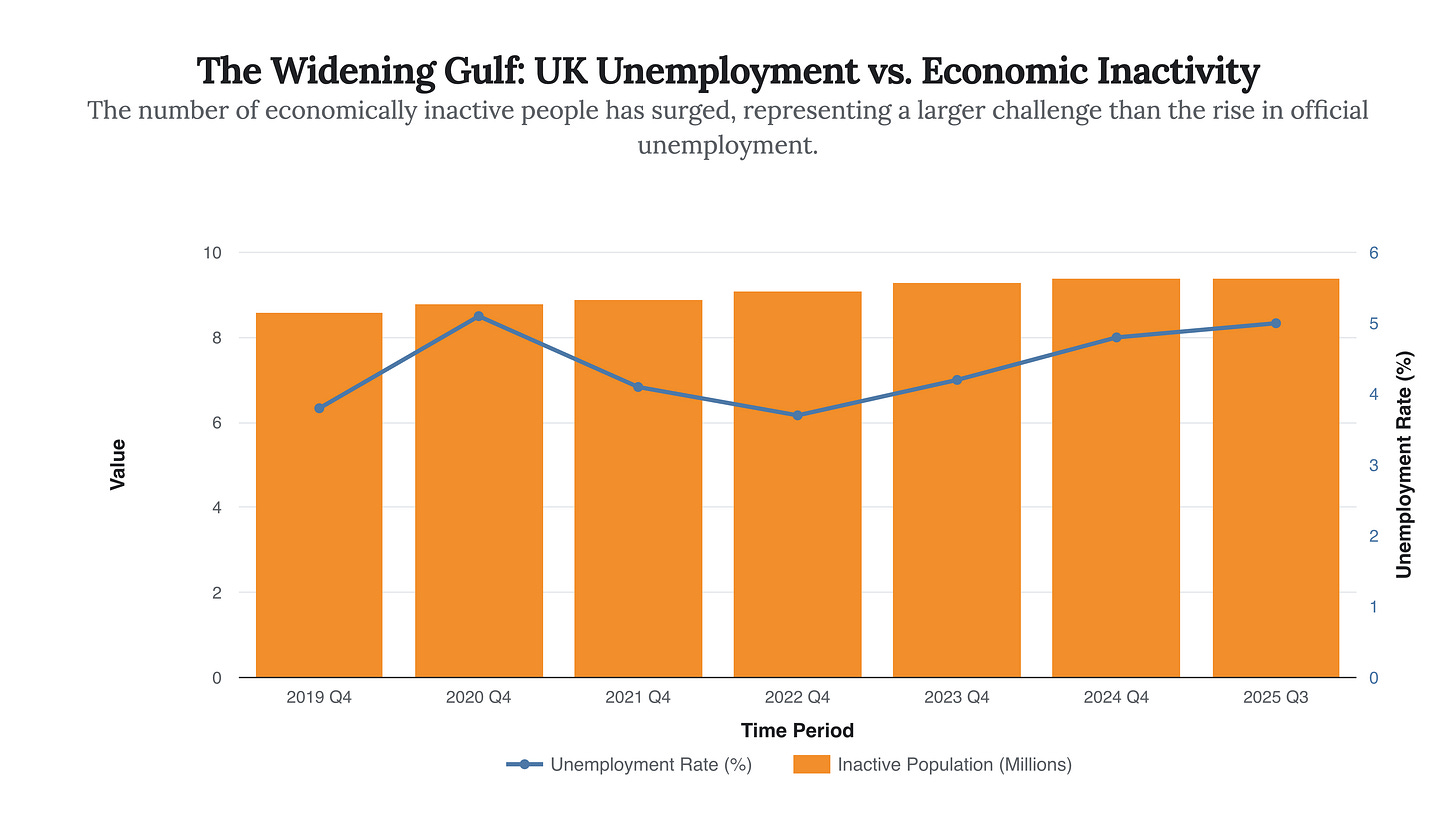

The Great Withdrawal: Britain’s Record Exodus into Economic Inactivity

The most critical variable in the UK labour market is not unemployment, but economic inactivity. While unemployment captures those out of work but actively seeking it, inactivity measures the vast and growing cohort of working-age individuals who have left the labour force entirely. Since the pandemic, this number has swelled by over 700,000, making the UK the only G7 nation where the employment rate has failed to recover to pre-pandemic levels. This is a uniquely British crisis, and at its heart is a public health emergency.

A Record Health Crisis

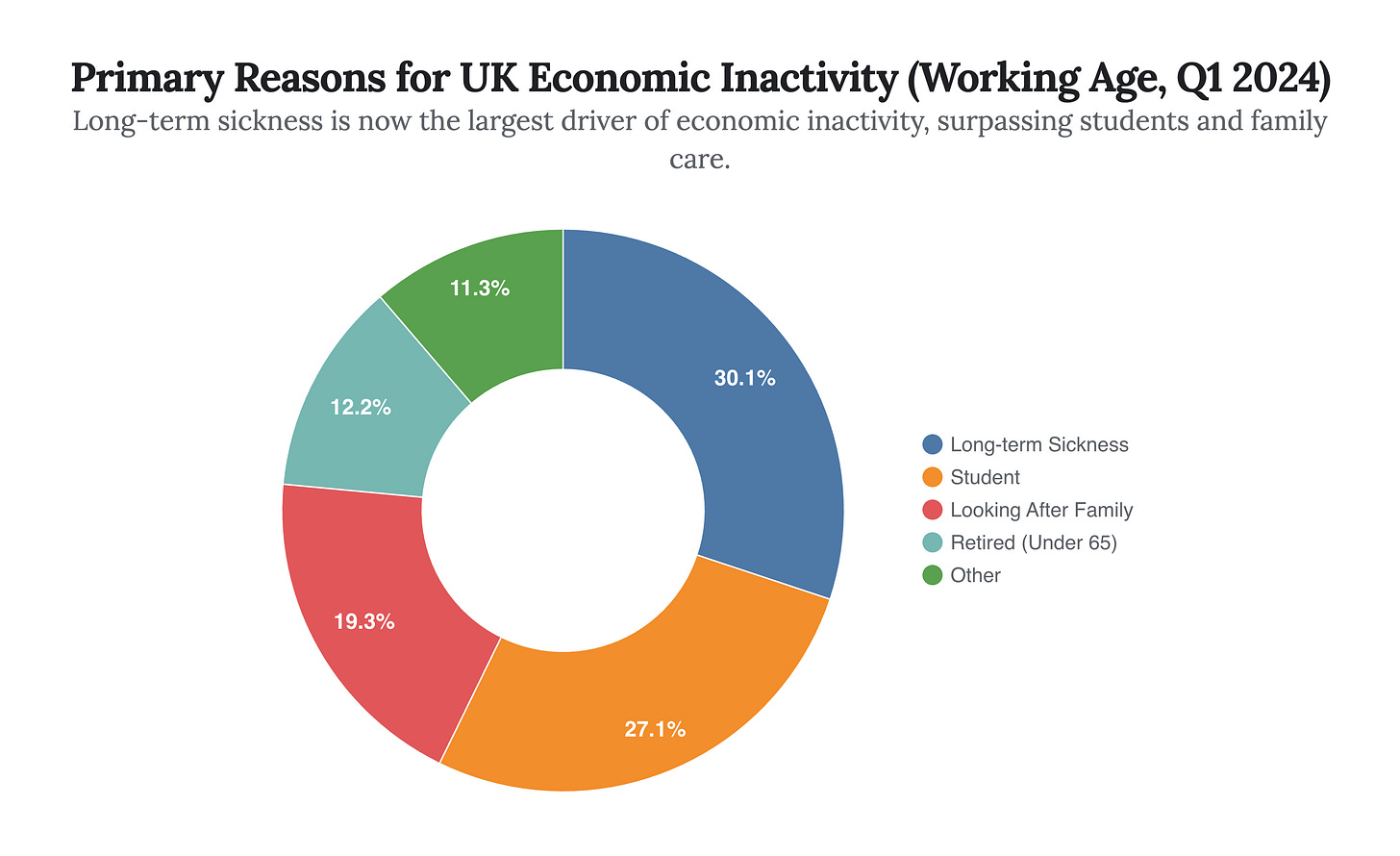

The principal driver of this exodus is a record-breaking rise in long-term sickness. As of early 2024, an estimated 2.8 million people were inactive due to chronic health conditions, a number that has been rising steadily since mid-2019, before the pandemic began. This trend has reversed a decade of progress in workforce participation among older workers and is now the dominant reason for leaving the labour market. The increase in inactivity has far outpaced the rise in unemployment, creating a structural deficit in the UK’s potential workforce. This is not a temporary blip; it reflects a sicker, smaller labour pool that will constrain economic growth for years to come.

The reasons for this health-driven inactivity are complex, encompassing NHS waiting lists, the rise of mental health conditions, and an aging population with more comorbidities. For businesses, the implications are immediate: a fiercer competition for talent, upward pressure on wages for the remaining workers, and a greater need to invest in employee wellbeing and flexible work arrangements to retain staff. For the government, it represents a profound fiscal challenge, with rising disability benefit claims and lost tax revenue.

The Lost Generation: A Deep Dive into the Youth Jobs Deficit

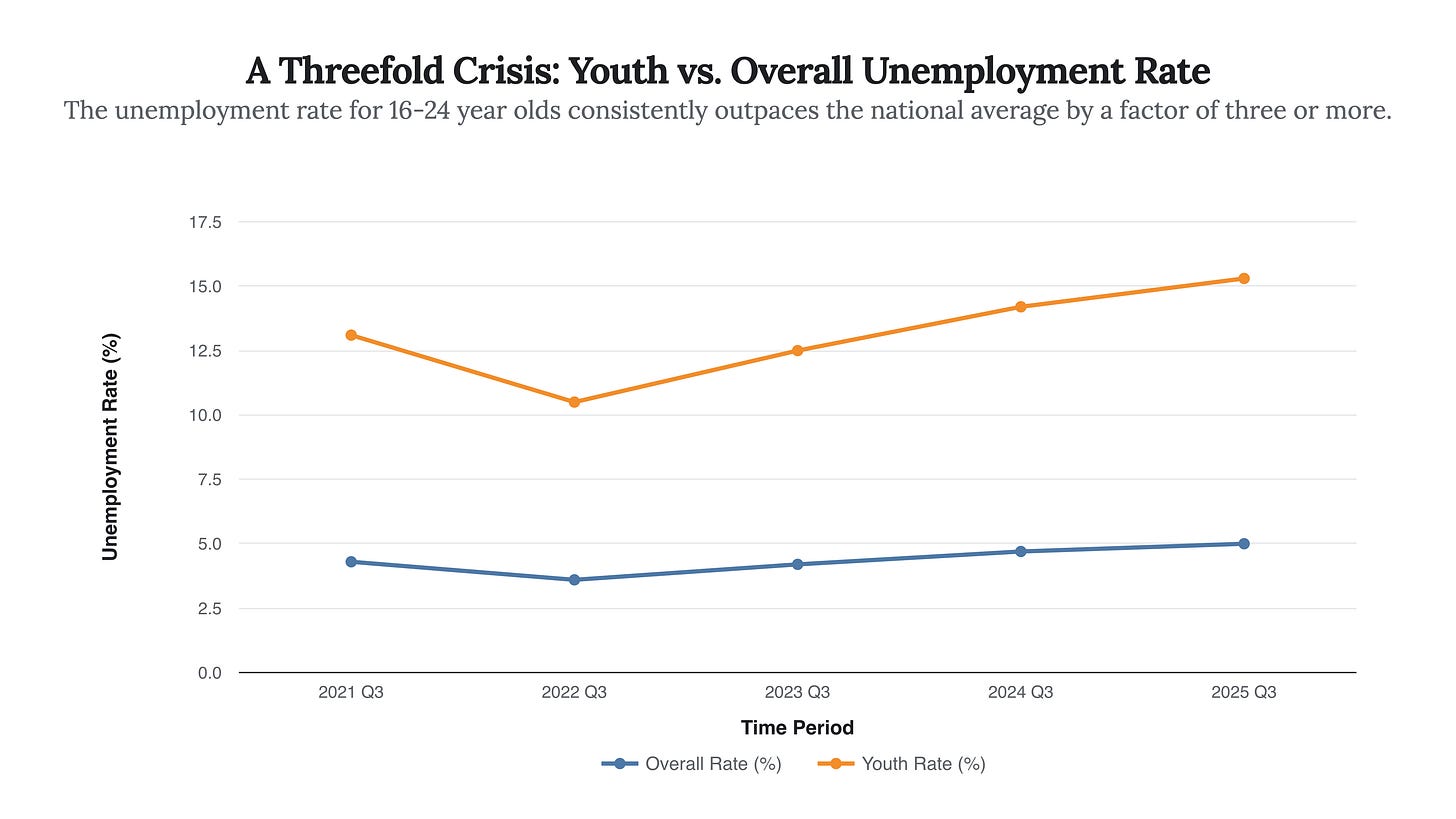

Running parallel to the inactivity crisis is an acute jobs deficit among the nation’s youth. The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds stood at 15.3% in the third quarter of 2025, more than triple the headline rate. This is not merely a reflection of labour market friction for new entrants; it is evidence of a deepening structural problem. Recent data shows that young people have borne the brunt of the economic slowdown, accounting for a shocking 46% of the 170,000 payroll jobs lost in the past year, despite making up only about a tenth of the workforce.

“I think we’ve got to get our act together. It’s a lost generation and if we don’t do something now the consequences economically, societally and personally will be devastating.”

- David Blunkett, former Labour Education Secretary

The Scourge of Long-Term Unemployment

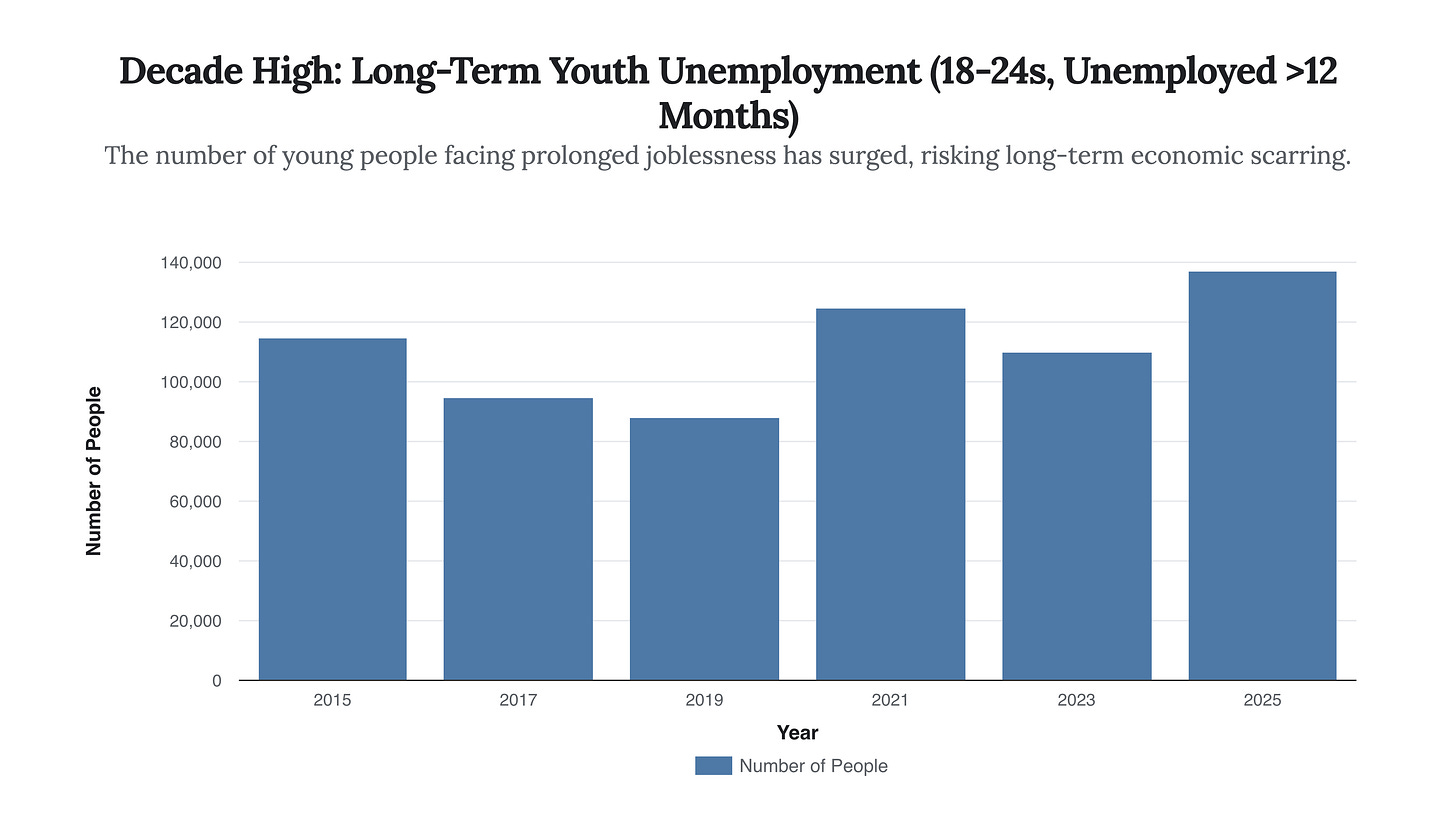

Even more concerning is the rise of long-term unemployment among the young, which inflicts lasting damage on career trajectories and lifetime earnings. The number of 18- to 24-year-olds out of work for more than a year has surged to 137,000, the highest level in a decade. This trend, combined with a growing number of young people who are Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET), points to a generation being left behind. The causes are multifaceted, ranging from a lack of entry-level opportunities and a skills mismatch to a significant increase in young people, particularly men, leaving the labour market due to poor mental health.

Strategic Foresight: Navigating the Consequences of a Shrinking Workforce

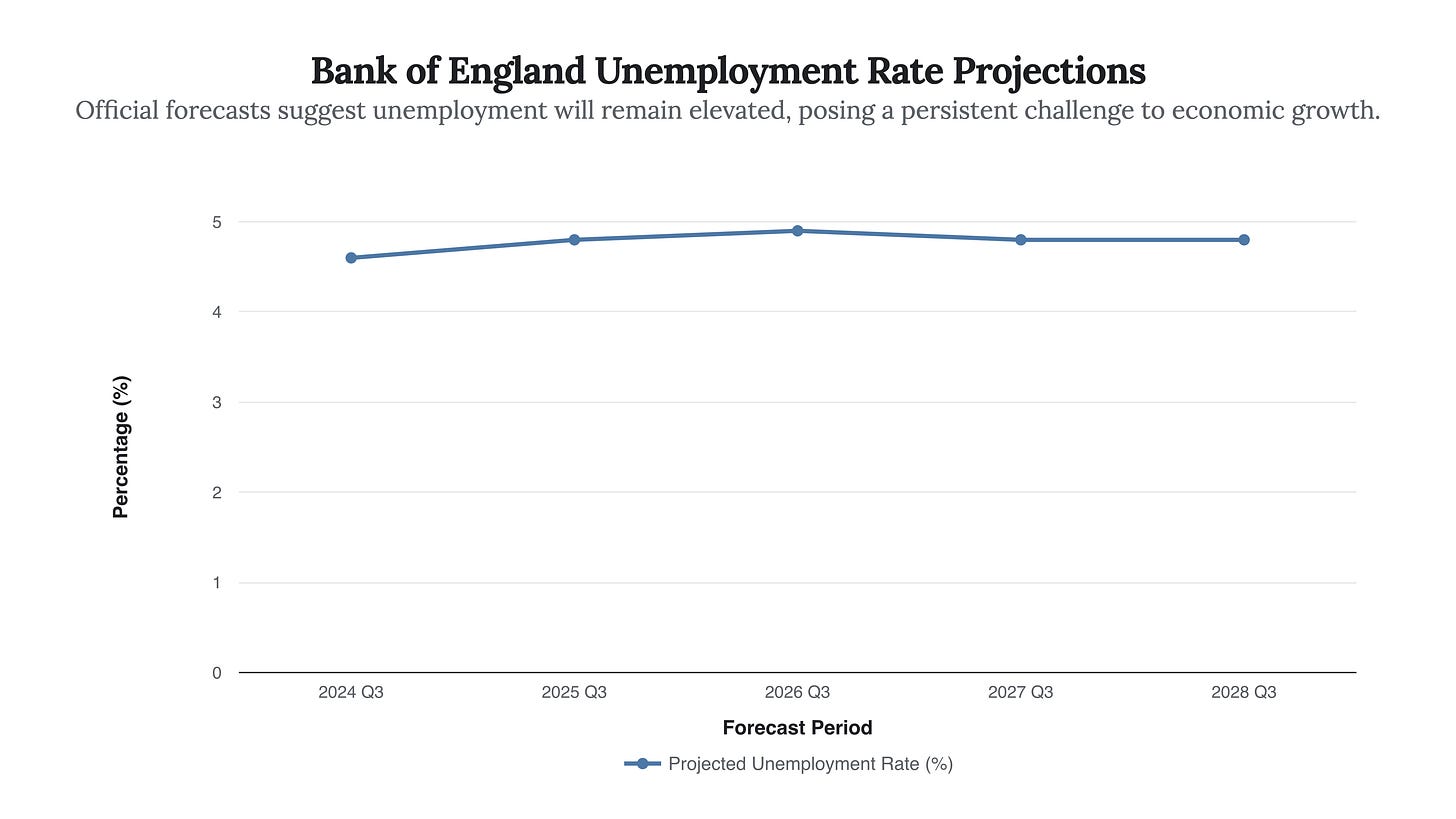

The confluence of record inactivity and a youth jobs crisis presents a formidable challenge to the UK’s economic future. The primary risk is a prolonged period of stagflationary pressure: low growth due to a smaller, less productive workforce, combined with persistent wage inflation as companies compete for a scarce supply of labour. The Bank of England’s forecasts already point to a delicate balancing act, with unemployment projected to hover near 5% through 2026 while inflation remains a concern.

Imperatives for Stakeholders

For Policymakers: The focus must shift from macro-level demand management to micro-level supply-side reform. This requires a two-pronged strategy: first, a radical, cross-departmental effort to tackle the drivers of long-term sickness, integrating healthcare, welfare, and employment support. Second, a new deal for young people is needed, focusing on vocational training, apprenticeships, and mental health support to prevent a generation from becoming permanently detached from the labour market.

For Investors: The shrinking labour pool is a material risk to corporate earnings, particularly in labour-intensive sectors like retail, hospitality, and social care. Companies with strong employee retention strategies, high levels of automation, and robust wellness programs are likely to outperform. A key due diligence question must now be: what is your strategy for labour supply resilience?

For Industry Leaders: The war for talent is no longer a turn of phrase but an economic reality. Businesses must innovate to survive. This means investing in automation and AI to boost productivity, creating flexible and supportive work environments to retain older, experienced workers, and building partnerships with educational institutions to create a pipeline of skilled young talent. Ignoring the health and wellbeing of the workforce is no longer a social issue but a direct threat to the bottom line.

The narrative of UK unemployment is a tale of two data sets. The headline figure, while worrying, is a symptom of a much deeper disease. The true crisis lies in the millions of people who have been removed from the economic equation altogether, either by ill health or a lack of opportunity. Addressing this structural decay of the UK’s human capital is the most urgent economic challenge of our time.

The strategic challenge for the United Kingdom is no longer simply creating jobs, but rather healing and engaging the workforce it already has.