The 25 Million-Person Gamble: How a New ‘Parallel State’ in Nyala Has Permanently Fractured Sudan

With the ‘Tasis’ government claiming 30% of the country, the civil war has evolved into a formalized partition.

It happened not with a bang, but with a swearing-in ceremony. On August 30, 2025, in the dusty heat of Nyala, South Darfur, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—better known as Hemedti—took the oath of office as President of the Sudan Founding Alliance, or “Tasis.” While the world watched the fighting in Khartoum, a new political reality quietly solidified in the west: Sudan now has two governments, two capitals, and two distinct destinies.

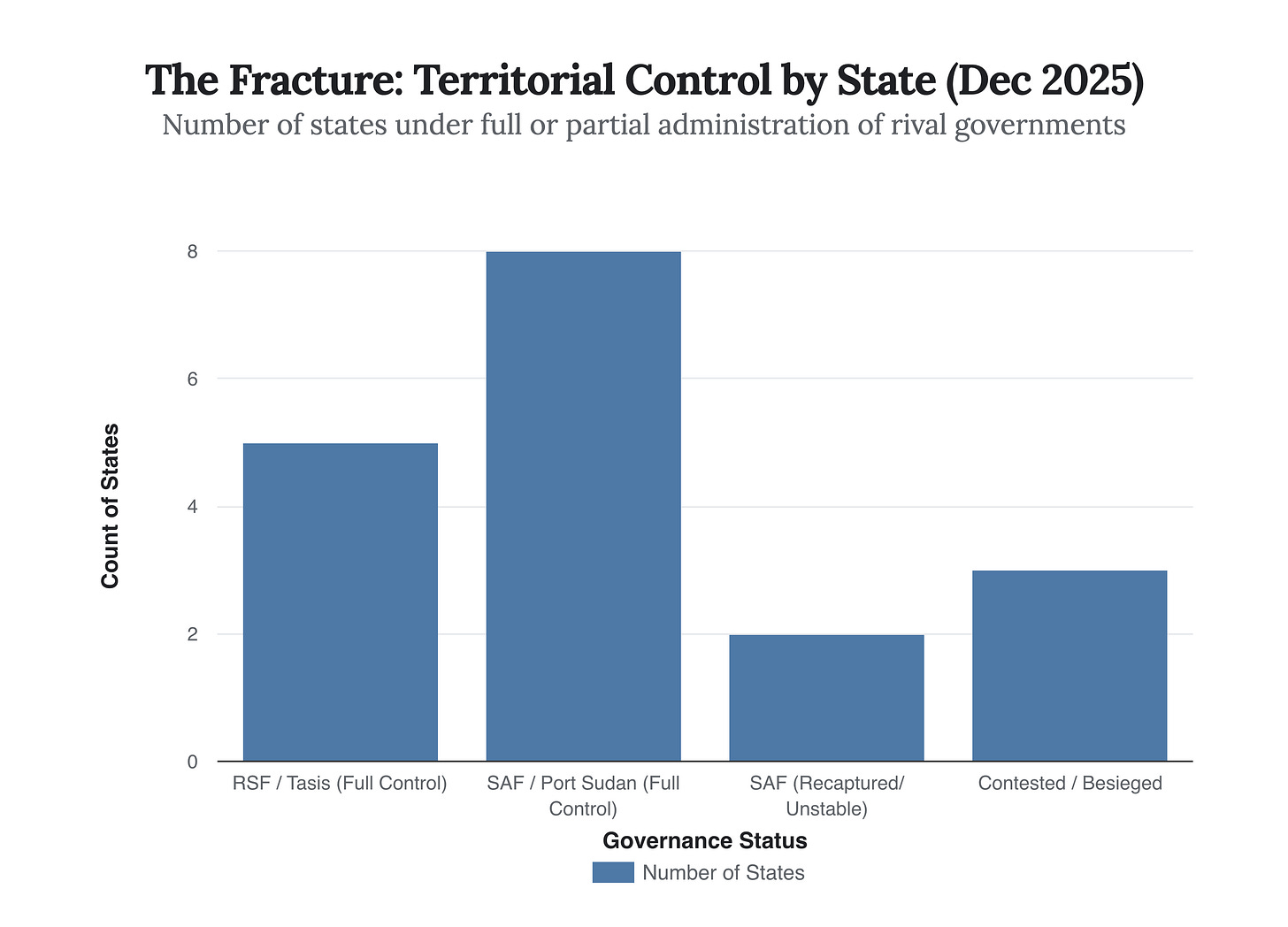

For over two years, the war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) was described as a chaotic power struggle. That narrative is now obsolete. With the formal establishment of the Tasis administration, which now governs a contiguous territory stretching from the borders of Chad to the outskirts of El Obeid, the conflict has mutated into a war between rival states. The data from December 2025 reveals a country not just divided by frontlines, but cleaved by governance structures that are becoming harder to dismantle by the day.

The chart above illustrates the new geography of power. The Tasis government now exercises full administrative control over five key states—including the entirety of the Darfur region (save for the besieged pockets of El Fasher)—effectively creating a “state within a state” larger than Germany. Meanwhile, the SAF-led government in Port Sudan has managed to consolidate the eastern and northern blocs, recently regaining a fragile hold on Khartoum and Gezira. This is no longer a fluid insurgency; it is a rigid partition.

The Legitimacy of Hunger

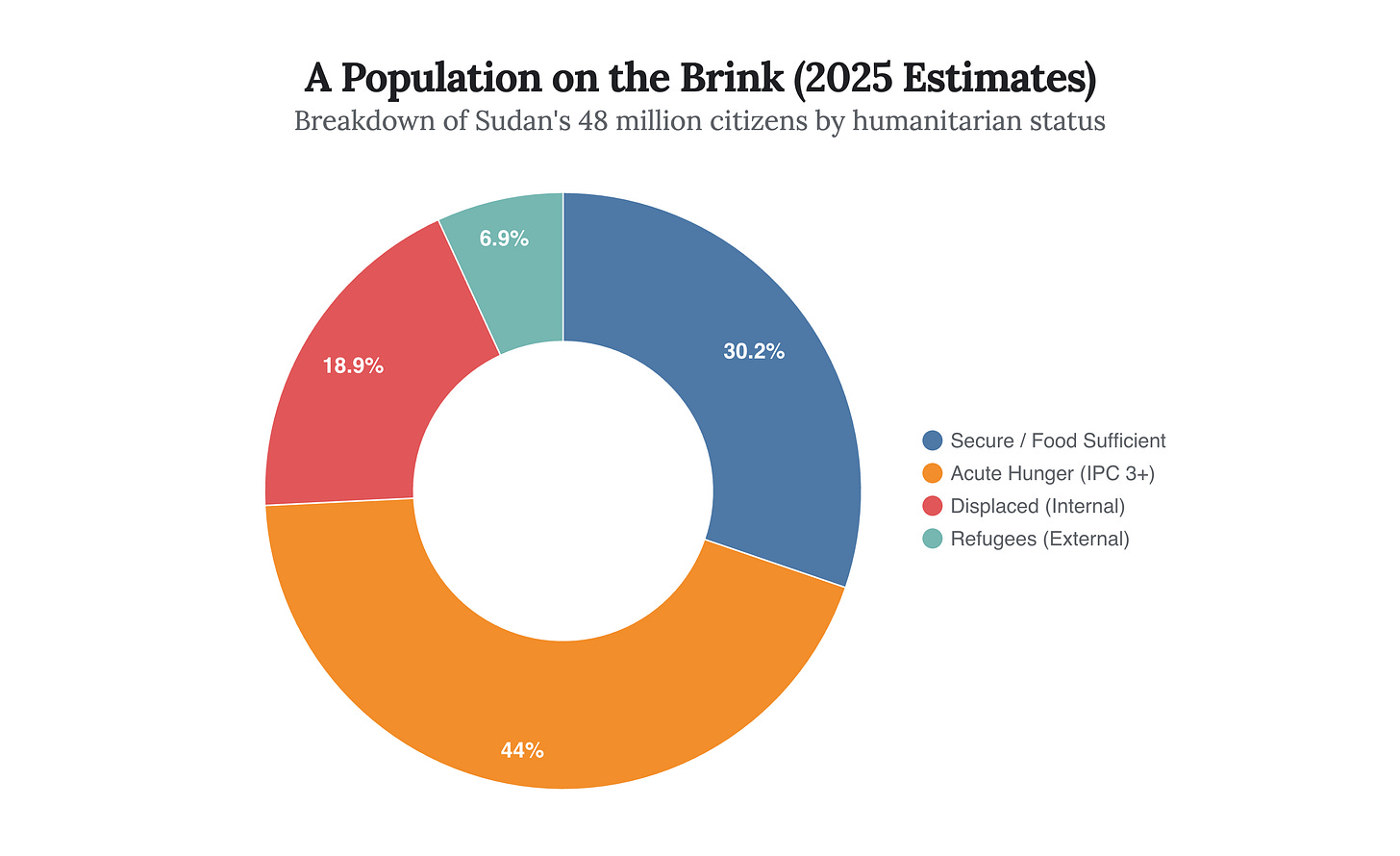

While the generals in Nyala and Port Sudan solidify their cabinets, the population they claim to rule is facing a catastrophe of historic proportions. The defining statistic of this parallel state governance is not tax revenue or troop numbers, but the sheer scale of human need. As of December 2025, the humanitarian data paints a grim picture of “governance” that fails to govern.

More than 25 million people—over half the population—are currently facing acute hunger. The Tasis administration, despite its cabinet of ministers for Finance and Infrastructure, has little capacity to feed the civilians in its territory. Instead, it relies on a “war economy” fueled by gold smuggling and checkpoint taxation. The United Nations and African Union have steadfastly refused to recognize the Tasis government, citing the risk of permanent fragmentation, but for the millions living under its rule, international recognition is less relevant than the daily struggle for sorghum and water.

“The volunteers have run the country for three years—they know absolutely everything. These volunteers have become the de facto civil service while the generals play at being presidents.”

The Economics of Two Sudans

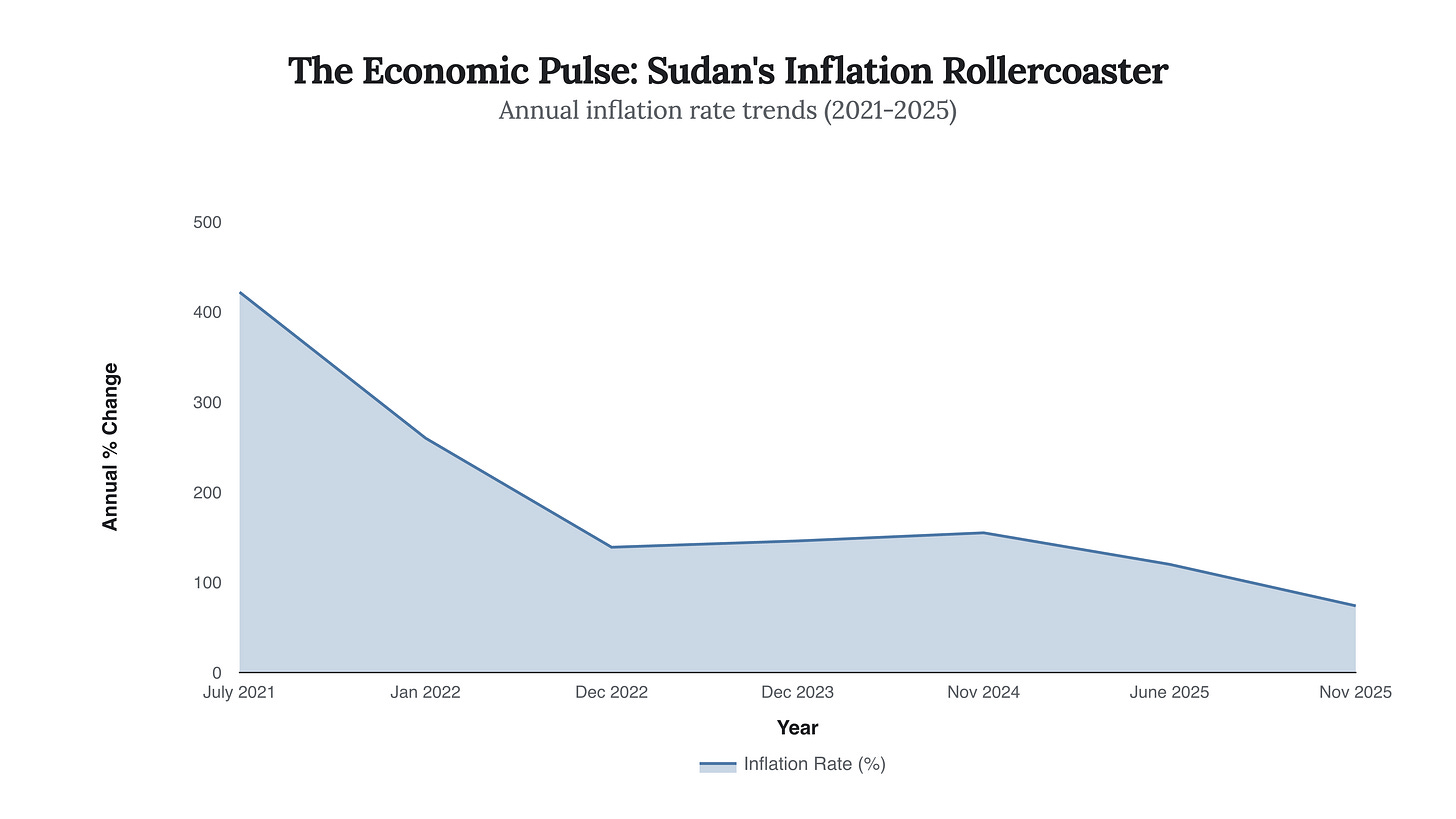

Perhaps the most surprising data point to emerge in late 2025 is the stabilization of inflation in the SAF-controlled zones. After peaking at over 400% in 2021 and remaining in triple digits through most of the war, inflation slowed to 74% in November 2025. This counter-intuitive trend suggests that the Port Sudan administration is successfully creating a functional, albeit beleaguered, economic fortress in the east, separate from the collapsed markets of the west.

This economic divergence further entrenches the split. The east is slowly integrating with Red Sea trade routes and global markets, while the west, under Tasis, is becoming an isolated enclave dependent on cross-border smuggling with Chad and the Central African Republic. The “Parallel State” is not just a political claim; it is becoming an economic reality with two different currencies, two different legal systems, and two different futures.

The Frozen Map

The formation of the Tasis government in Nyala was not a desperate gamble by a losing faction, but a calculated move to formalize the status quo. By appointing a Prime Minister and regional governors, Hemedti and his allies in the SPLM-N (Al-Hilu faction) have signaled that they are no longer interested in capturing Khartoum—they are building their own capital.

The tragedy of Sudan’s parallel state governance is that it works just well enough to sustain the war, but nowhere near well enough to sustain the people. As we move into 2026, the world must reckon with a Sudan that exists only on maps. On the ground, the partition is already complete.