How Micron’s 40-Football-Field “Nothingness” Rewrites Manufacturing

Inside the 2.4 million square foot cleanroom where a single speck of dust is a billion-dollar disaster

It is January 2, 2026, and the most expensive air on the planet is currently circulating in Gujarat, India. Just days ago, on December 29, 2025, Micron Technology officially completed the civil construction of its new semiconductor facility in Sanand, transitioning from a construction site to a live operational hub. While the ribbon-cutting in India marks a critical victory for the global supply chain, it is merely the opening salvo in a much larger war on contamination. As Micron validates these new cleanrooms, a far more colossal project is rising in Clay, New York—a “Megafab” so vast it defies conventional architectural logic.

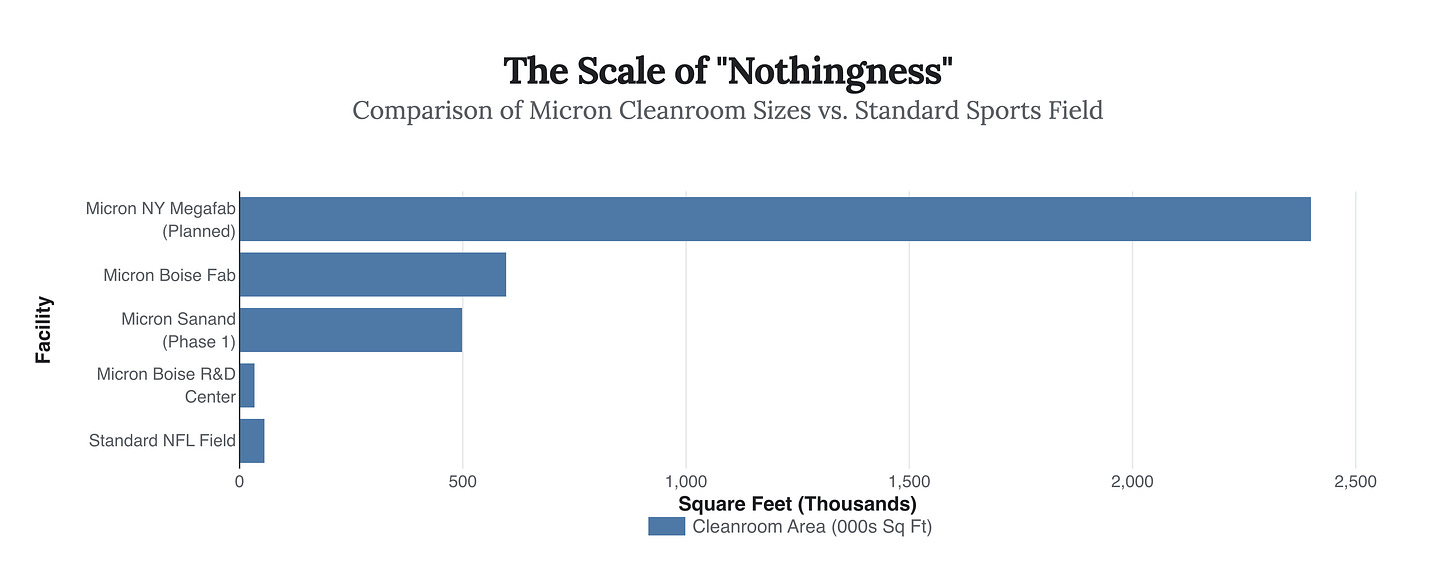

The numbers emerging from Micron’s expansion strategy suggest a fundamental shift in industrial economics. We are no longer building factories; we are constructing cathedral-sized scientific instruments. The New York facility alone will eventually encompass 2.4 million square feet of cleanroom space—roughly the size of 40 U.S. football fields stitched together. But unlike a stadium, this space must be maintained at a level of purity that makes a hospital operating room look like a dirty sidewalk. The defining characteristic of these facilities is not what is inside them, but what is rigorously kept out.

Micron’s New York facility will contain 40x more cleanroom space than an NFL stadium, yet requires air 10,000x purer than the stadium’s luxury suites.

The chart above reveals the sheer industrial ambition at play. The New York Megafab dwarfs even the company’s significant expansion in Boise, Idaho, which itself boasts the largest single cleanroom ever built in the United States. To understand the engineering challenge, one must look at the air itself. In a standard office environment, the air is thick with millions of microscopic particles—dead skin, dust, pollen. In a Micron fab, these particles are the enemy. A single particle larger than 0.1 microns (1/1000th the width of a human hair) can destroy a microchip that took months to fabricate.

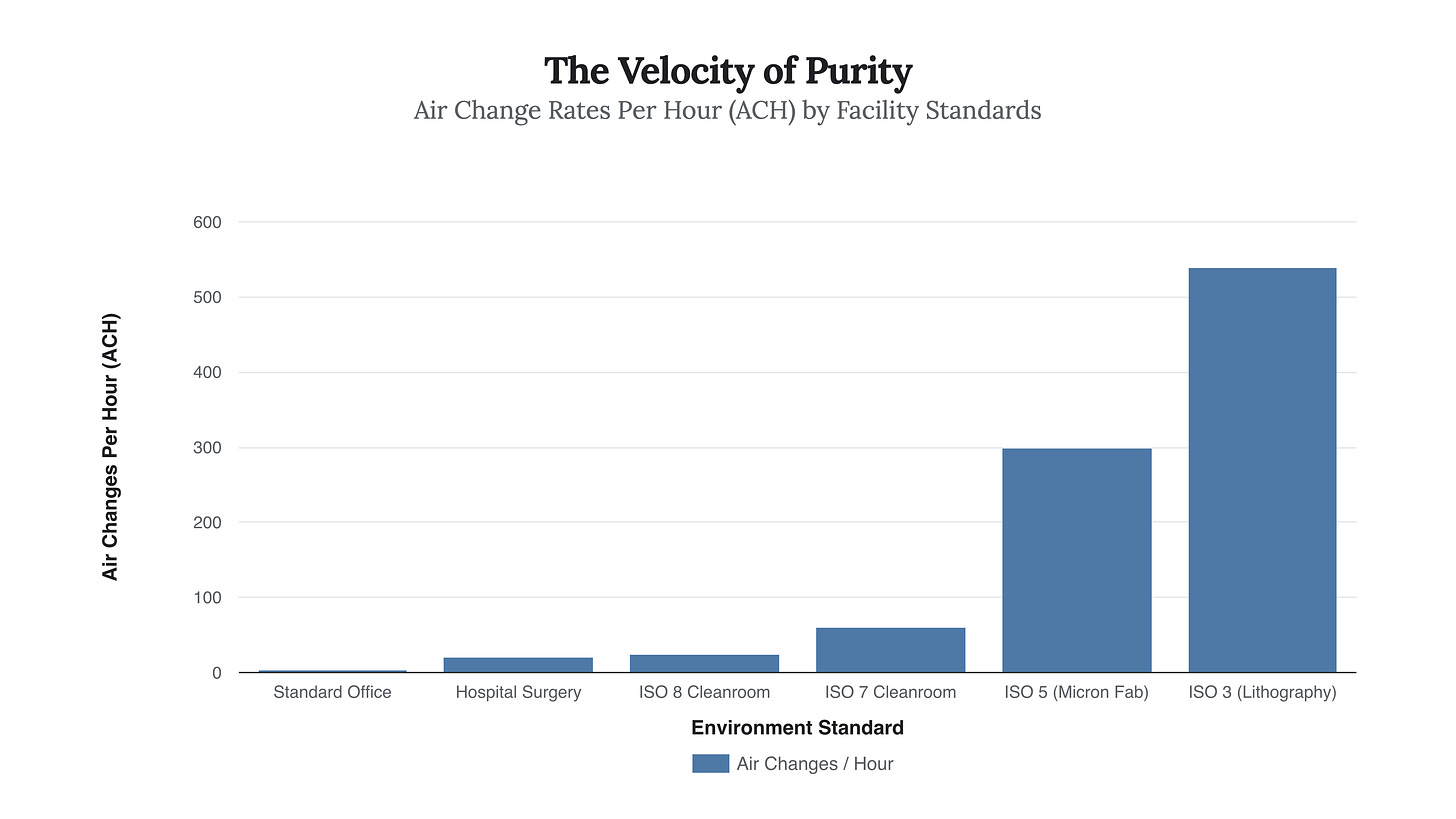

To combat this, the air in these facilities is not just filtered; it is replaced with obsessive frequency. While a standard commercial building might change its air 2 to 4 times an hour, a Class 1 semiconductor cleanroom demands a total air change every 6 to 12 seconds. The result is a violent, invisible storm of purification that requires massive energy and infrastructure, all to maintain a stillness that allows for atomic-level precision.

A modern semiconductor fab replaces its entire air volume up to 27 times faster than a hospital operating room.

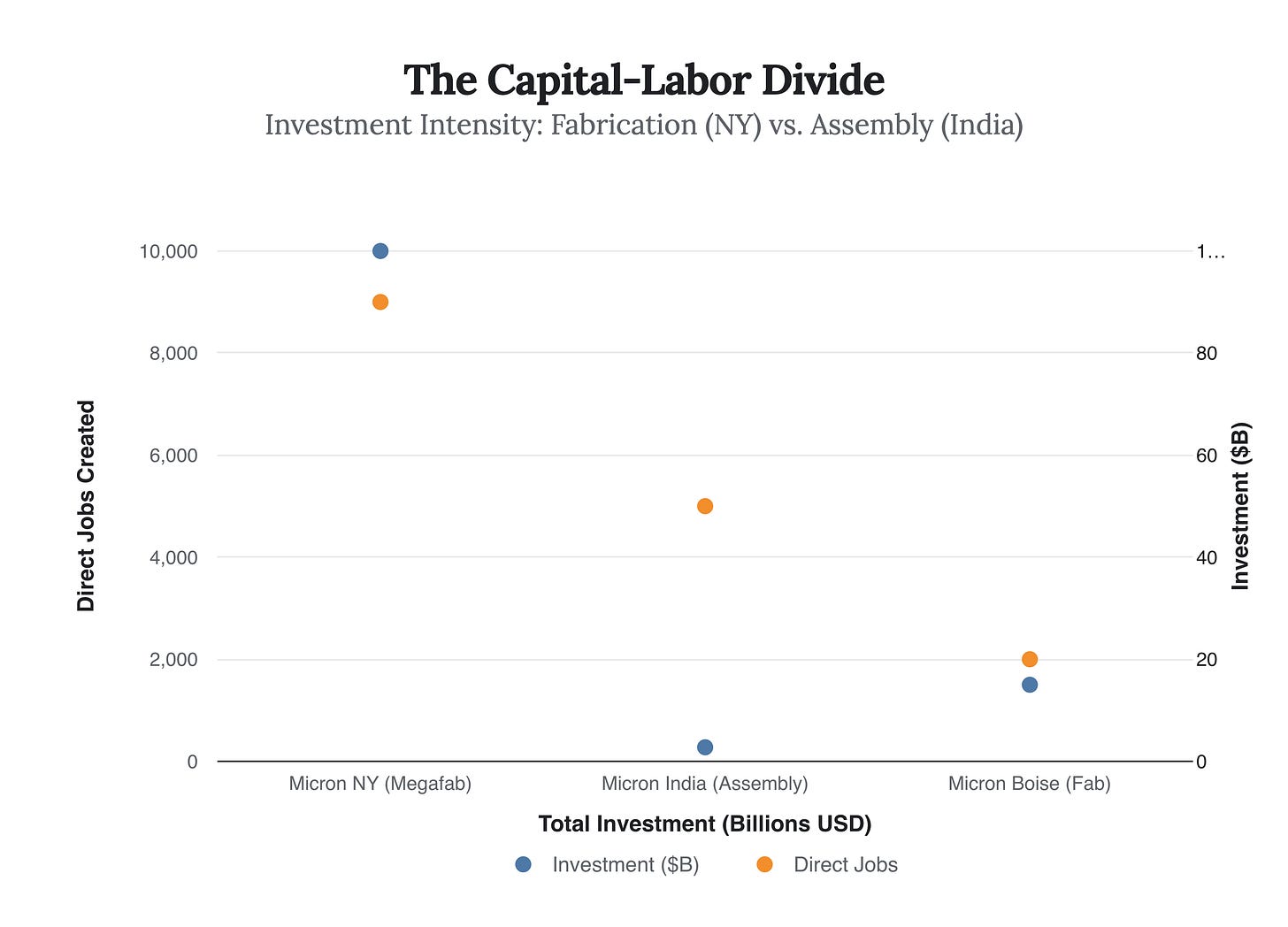

This obsession with purity drives the economics of the entire operation. The capital intensity of these facilities has created a bifurcation in the industry. As the recent completion of the Sanand facility in India demonstrates, there is a distinct difference between “frontend” fabrication (manufacturing the chips) and “backend” assembly (packaging them). The Sanand plant, focused on assembly and test, represents a $2.75 billion investment. In contrast, the New York fabrication site is a $100 billion endeavor.

“The foundation of the [Boise] building required 24,000 cubic yards of concrete, the equivalent of a concrete truck delivery every hour for 100 days straight.”

The disparity reveals a hidden truth about the semiconductor economy: fabrication is capital-intensive, while assembly is labor-intensive. The New York Megafab is designed to be a highly automated machine that turns electricity and silicon into memory, requiring massive capital but relatively fewer humans per dollar invested compared to assembly operations. This “Capability Cliff” is visible when we plot the investment dollars against the direct jobs created at each major site.

It costs Micron ~$11 million in capital to create one job in New York, versus ~$0.55 million per job in India, revealing the extreme automation of modern fabs.

As Micron pushes forward with its validations in India and breaks ground on the massive New York expansion, the definition of a “factory” is being rewritten. These are not merely buildings; they are geo-political assets made of concrete and filtered air. The 2.4 million square feet of cleanroom space coming to New York represents more than just capacity; it represents a strategic bet that the control of dust—at a scale of 40 football fields—is the new currency of national security.

The era of the simple factory is over; in 2026, industrial power is measured in the emptiness of the air you can afford to enclose.