How Hannah Arendt’s “Banality of Evil” Reappears in Algorithmic Decision Systems and Automation Data

The $16 Billion Thoughtlessness Tax: Why 85% of Algorithmic Compliance Is Performative Theater

In 1963, Hannah Arendt reported from Jerusalem on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, expecting to find a monster. Instead, she found a bureaucrat. Her resulting thesis—the “Banality of Evil”—argued that great harm often arises not from malevolence, but from a specific kind of thoughtlessness: the inability to think from the standpoint of somebody else, coupled with a rigid adherence to administrative procedure. Eichmann was not a demon; he was a “joiner” who prioritized the efficiency of the system over the reality of its consequences.

Sixty years later, this specific form of administrative evil has found a perfect new host. It has migrated from the paper-pushing bureaucrat to the algorithmic decision system. Today’s “desk murderers” are not people, but predictive models optimizing for efficiency, fraud detection, or cost savings with zero capacity for moral reflection.

The strategic crisis facing modern enterprises and governments is not “rogue AI” or sentient machines. It is the industrialization of thoughtlessness. As organizations rush to automate complex decision-making, they are inadvertently building the most efficient engines of administrative dissociation in history. The cost of this error is no longer theoretical. Recent data from the Netherlands, Australia, and the United States reveals that the financial penalty for this “algorithmic banality” has already exceeded $16 billion, with the human cost far higher.

The Administrative Massacre: Quantifying the Cost of Dissociation

Arendt described the bureaucratic machine as a device that creates “distance” between the decision-maker and the subject. Modern algorithmic systems perfect this distance. The data scientist optimizing a fraud model never sees the family evicted by a false positive. The claims adjuster clicking “Approve” on an AI-generated denial never sees the patient denied care.

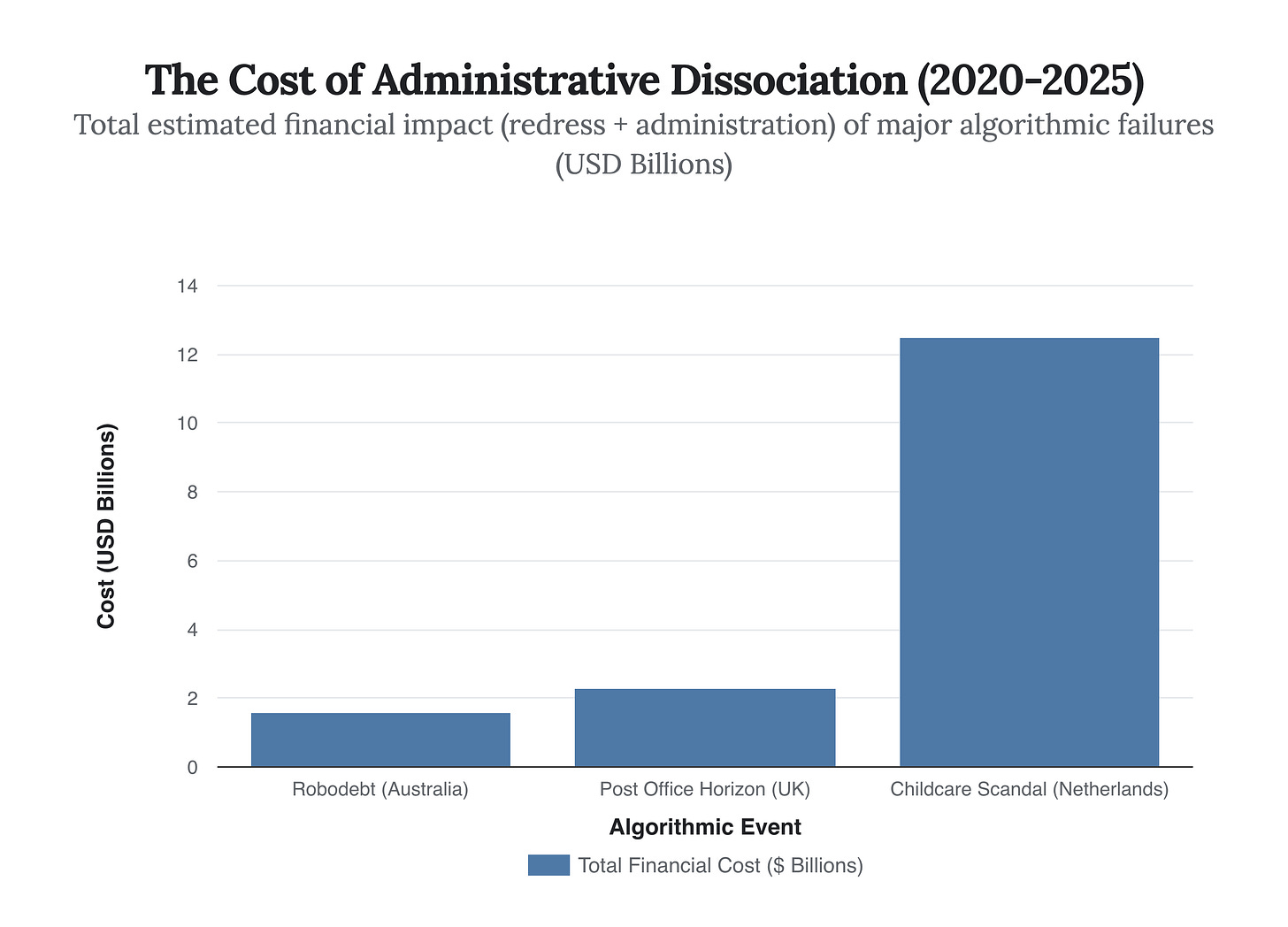

We can now quantify the price of this distance. Three major government-scale failures—the Dutch Childcare Benefit Scandal (Toeslagenaffaire), Australia’s “Robodebt,” and the UK Post Office Horizon scandal—serve as the primary case studies. In each instance, an algorithmic system flagged anomalies as fraud or debt, and the human bureaucracy treated the system’s output as infallible truth. The result was not just error, but the systematic destruction of lives, followed by massive financial reparations.

Figure 1: The financial fallout of “thoughtless” automation. The Dutch Childcare Benefit Scandal alone is projected to cost nearly $12.5 billion (€11.7bn) in compensation and recovery operations, illustrating the asymmetric risk of automated fraud detection.

The Dutch case is particularly Arendtian. The tax authority’s algorithm used “dual nationality” as a risk indicator for fraud—a variable that mathematically optimized their hit rate but morally constituted discrimination. Thousands of families were driven to bankruptcy. The system worked exactly as designed; the evil lay in the design’s blindness to the human reality of its variables. The $12.5 billion recovery cost is a direct tax on the government’s failure to maintain what Arendt called the “two-in-one” dialogue of conscience.

The Vigilance Decay: Why Humans Can’t “Loop” In

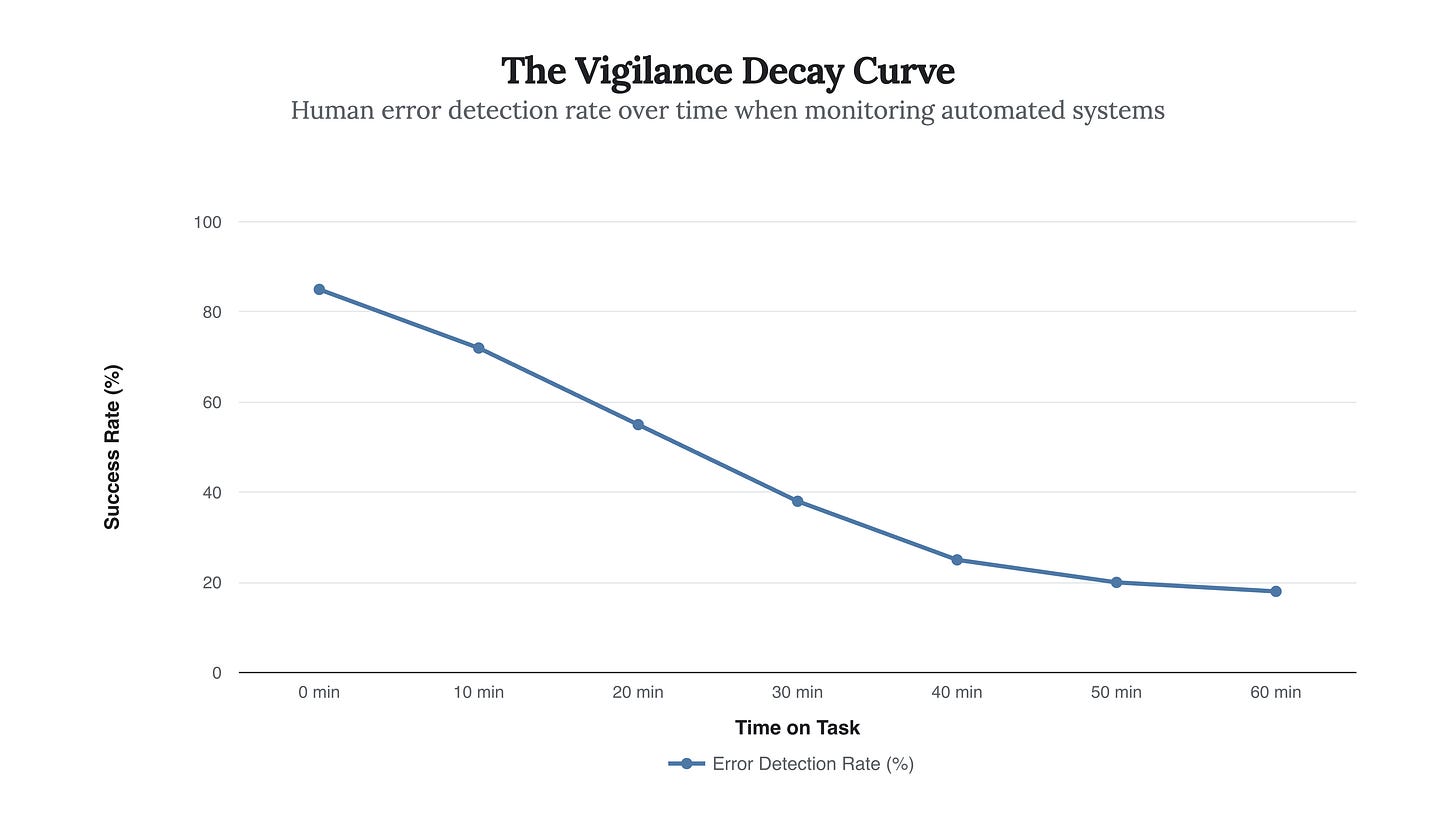

The standard industry defense against algorithmic harm is the “Human-in-the-Loop” (HITL) protocol. The theory suggests that if a human reviews the AI’s decision, the moral vacuum is filled. Current research proves this is a dangerous fallacy. Placing a human in front of an automated system does not reintroduce judgment; it introduces automation bias.

When an algorithm presents a conclusion with high confidence (or simply high frequency), the human operator’s brain cognitively offloads the analytical work. This is the “rubber stamp” phenomenon. Data on operator vigilance shows a catastrophic decline in error detection rates after just minutes of monitoring an automated system.

Figure 2: The “Human-in-the-Loop” fallacy. Research indicates that after 45 minutes of monitoring an automated system, human operators fail to detect 80% of the system’s errors, effectively becoming rubber stamps for the machine’s logic.

This decay creates a paradox: the more accurate the AI becomes, the less capable the human becomes of catching the rare but critical failure. In the Robodebt case, the “human check” became a fiction—operators were incentivized to

process claims quickly, which meant agreeing with the machine. They became the “cogs” Arendt warned about, their agency surrendered to the script.

The Scale of Denial: The nH Predict Case

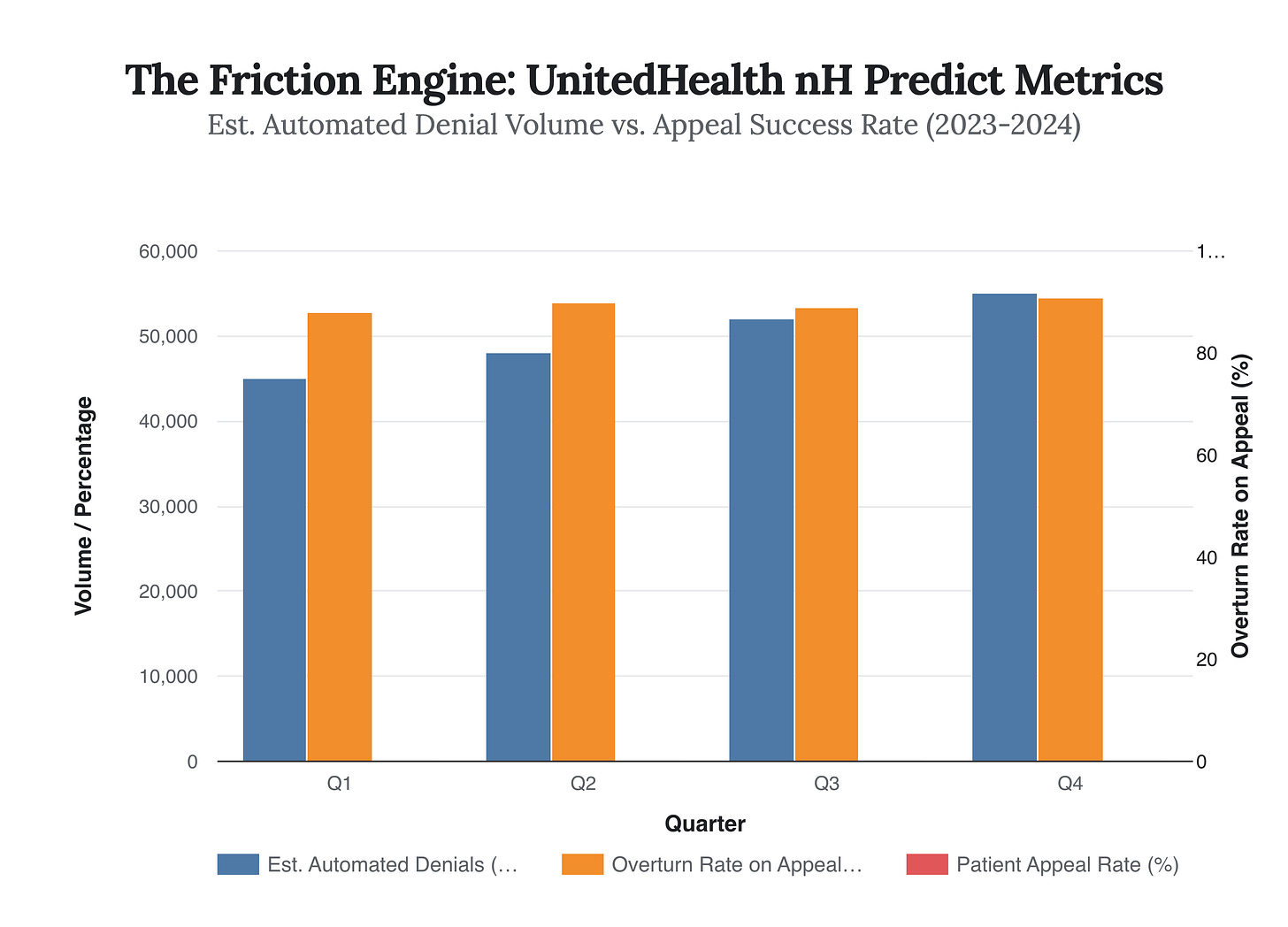

Nowhere is the banality of evil more evident than in the U.S. healthcare sector’s use of algorithms for claims adjudication. Lawsuits against major insurers regarding the nH Predict algorithm allege a system designed to manufacture denial. The algorithm predicts a length of stay for post-acute care that is often far shorter than what physicians recommend.

The “evil” here is not in the denial itself, but in the friction. The system relies on the fact that the vast majority of patients, when faced with an authoritative, data-backed denial, will simply give up. It is a war of attrition waged by code. The data reveals a staggering discrepancy between the volume of automated denials and the success rate of the few who summon the energy to fight back.

Figure 3: The disparity between the machine’s output and reality. While the algorithm allegedly issues tens of thousands of denials (bars), nearly 90% of those challenged are overturned (line). However, the patient appeal rate (secondary line) remains near 0.2%, proving the strategy relies on passivity, not accuracy.

This chart demonstrates the core mechanism of algorithmic banality:

Asymmetry of Effort. It costs the machine fractions of a cent to issue a denial; it costs the human hours of agony to refute it. Arendt’s “inability to think” is systematized here—the algorithm cannot “think” about the patient’s pain, and the human reviewers are often pressured to adhere to the algorithm’s predicted length of stay to meet productivity metrics.

The Compliance Theater: The Rise of the “Apology Industry”

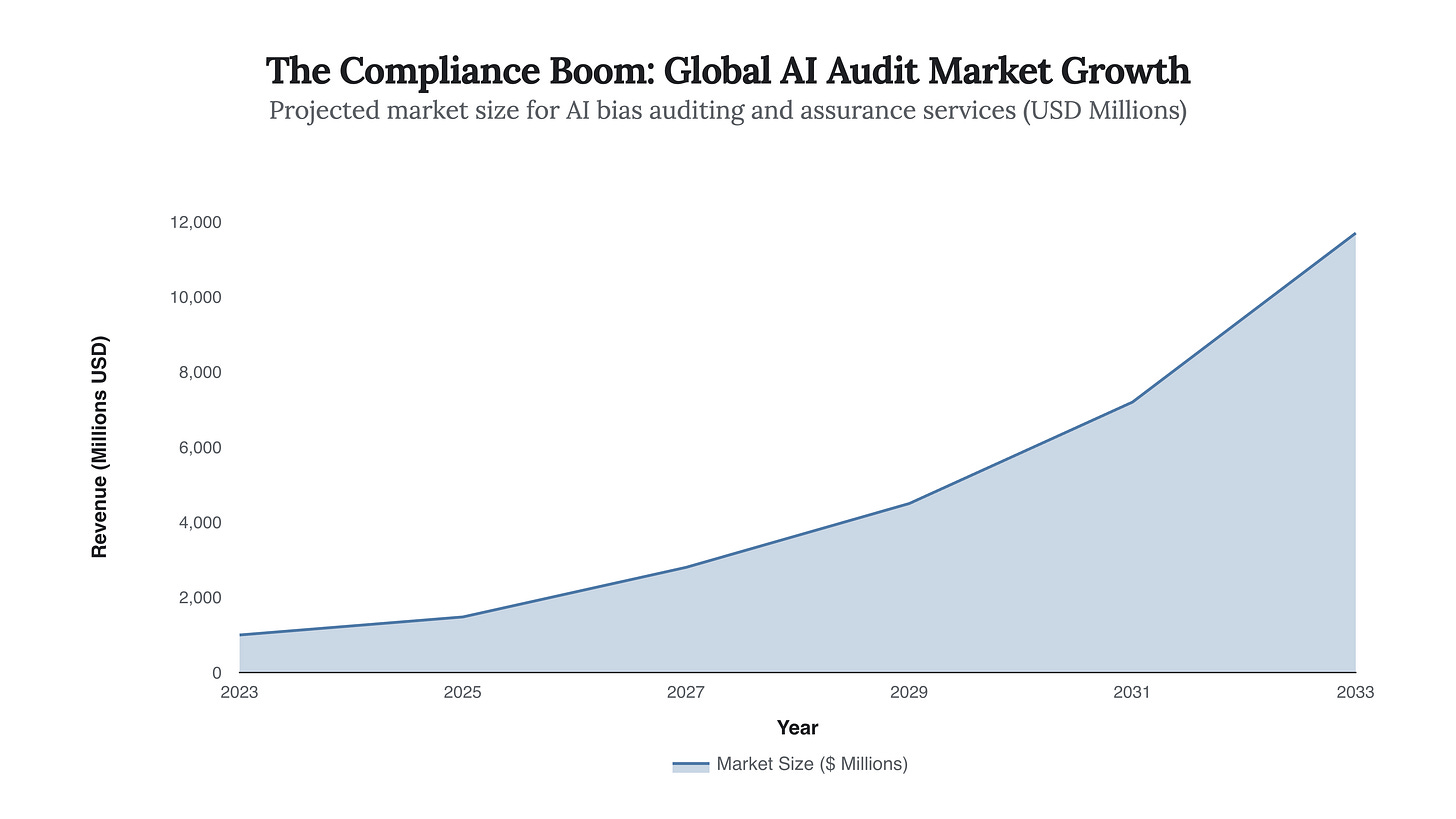

In response to these catastrophes, a new industry has emerged: Algorithmic Auditing. Corporations are rushing to purchase “fairness” and “bias mitigation” tools. However, much of this activity mirrors the empty bureaucratic compliance Arendt observed—forms filled out to satisfy the record, not to change the reality.

The market for AI auditing is exploding, yet the rate of algorithmic incidents continues to rise. This divergence suggests that we are investing in performative compliance—tools that measure the bias of a model without addressing the fundamental dissociation of the system.

Figure 4: The industry of apology. The AI Audit market is forecast to grow from $1B to nearly $12B by 2033. Despite this investment, the fundamental dynamic of “thoughtless” automated decision-making remains largely unchallenged.

The New “Nuremberg Defense”

In the courtroom, Eichmann claimed he was merely a transmitter of orders. Today’s executives claim they are merely the deployers of models. “The model said so” is the new “I was just following orders.” The diffusion of responsibility is now absolute. The developer blames the training data; the user blames the interface; the executive blames the vendor. The result is a moral vacuum where billions of dollars of harm can occur without a single individual feeling personally responsible.

Strategic Implications: The Right to Friction

For decision-makers, the lesson of the $16 billion “thoughtlessness tax” is that efficiency without friction is a liability. The seamlessness of the digital process is what allows the banality of evil to flourish. To prevent future catastrophes, we must strategically reintroduce moral friction into our systems.

Predictions for 2025-2030

The End of the “Black Box” Defense: Courts will increasingly rule that using