Flight of the Dragon: An Intelligence Briefing on China’s Low-Altitude Economy

How Beijing’s concerted state-capitalist strategy is engineering global dominance in the flying car industry before it even takes off.

A new reality in mobility is taking flight, and its operational epicenter is China. While Western competitors navigate complex regulatory frameworks and focus on piloted prototypes, China has already begun commercial operations of autonomous passenger-carrying drones. This is not a speculative future; it is happening now in the skies above cities like Guangzhou and Hefei. Beijing’s ambition, however, extends far beyond launching a few novel air taxis. It is executing a meticulous, top-down strategy to build and dominate the entire ‘low-altitude economy’—a comprehensive ecosystem of aerial vehicles, air traffic control systems, infrastructure, and services operating below 3,000 meters.

This intelligence briefing deconstructs China’s multi-layered strategy, analyzes the key corporate players leading the charge, maps the technological and regulatory terrain, and provides a forward-looking assessment of the strategic implications for global industry and policymakers. What is unfolding is not merely the birth of a new vehicle category but a masterclass in state-directed industrial policy aimed at seizing a commanding lead in a sector projected to be worth trillions.

The Mandate from Heaven: Engineering an Economic Revolution from the Air

The velocity of China’s ascent in the electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) sector is no accident. It is the direct result of a centrally orchestrated national strategy. In March 2024, the “low-altitude economy” was officially written into the Government Work Report, and it has since been enshrined in the 15th Five-Year Plan as a strategic emerging industry, placing it on par with priorities like artificial intelligence and commercial aerospace. This designation has unlocked a torrent of state support, transforming the sector from a niche technological pursuit into a pillar of future economic growth.

Policy as a Propulsion System

Beijing’s approach is a textbook example of its unique brand of state capitalism. The central government sets the vision, and provincial and municipal governments rush to implement it with tangible support. At least 29 provincial governments have now included the low-altitude economy in their annual work reports, up from just 16 in 2023. This has translated into a suite of potent incentives, including direct subsidies for R&D, government-backed venture capital funds, and the designation of numerous national pilot zones to fast-track development and testing. For example, Guangdong province, a manufacturing powerhouse, has laid out an action plan to build a low-altitude economy worth over RMB 300 billion (US$41.4 billion) by 2026 alone. To coordinate these efforts, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has even established a dedicated department to draft strategies and overcome key challenges in the sector.

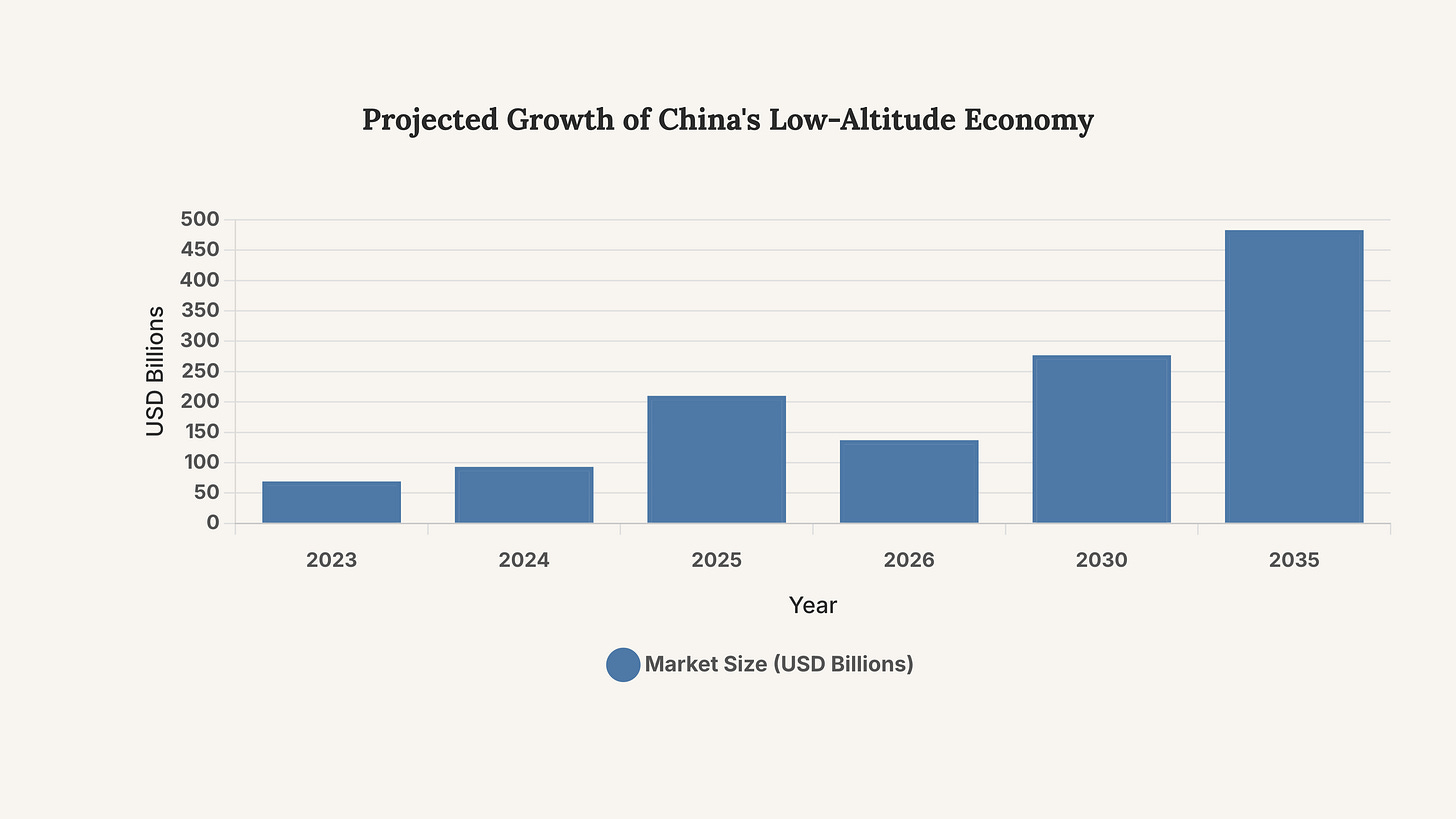

This chart illustrates the aggressive growth trajectory forecast for China’s low-altitude economy, underpinned by immense state investment and policy support. The figures represent a blend of projections from the CAAC and other industry analysis reports, highlighting the scale of Beijing’s ambition.

The CAAC’s Deliberate Speed

Perhaps the most critical component of China’s strategy is its unique regulatory approach. The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) has adopted a flexible, accelerated certification pathway that stands in stark contrast to its Western counterparts like the FAA and EASA. The CAAC has strategically prioritized the certification of autonomous, unmanned aircraft first, viewing logistics drones and pilotless passenger vehicles as the quickest path to commercialization. This has allowed companies like EHang to achieve a global first: securing the complete set of Type Certificate (TC), Production Certificate (PC), Airworthiness Certificate (AC), and Air Operator Certificate (AOC) for its autonomous passenger eVTOL, the EH216-S. While Western regulators grapple with the complexities of certifying novel piloted aircraft to a “one in a billion” catastrophic failure probability, the CAAC’s approach has enabled real-world commercial operations to begin, providing invaluable operational data.

The Constellation of Competitors: A Multi-Pronged Assault on the Skies

China’s flying car industry is not a monolithic entity. It is a dynamic ecosystem of state-backed incumbents, agile startups, and automotive giants, each pursuing distinct technological pathways. This internal competition, fostered by the state, is designed to produce multiple champions capable of competing across different market segments.

The Vanguard: EHang’s Autonomous Breakthrough

EHang is the undisputed trailblazer. By focusing exclusively on autonomous passenger drones from its inception, the Guangzhou-based company has leapfrogged competitors globally. Its EH216-S, a two-seater multicopter, has completed over 60,000 test flights and is now conducting paid aerial sightseeing tours in designated zones. This first-mover advantage in commercial operations is a significant strategic asset, allowing EHang to refine its technology, build public trust, and establish operational expertise while others are still in the certification queue.

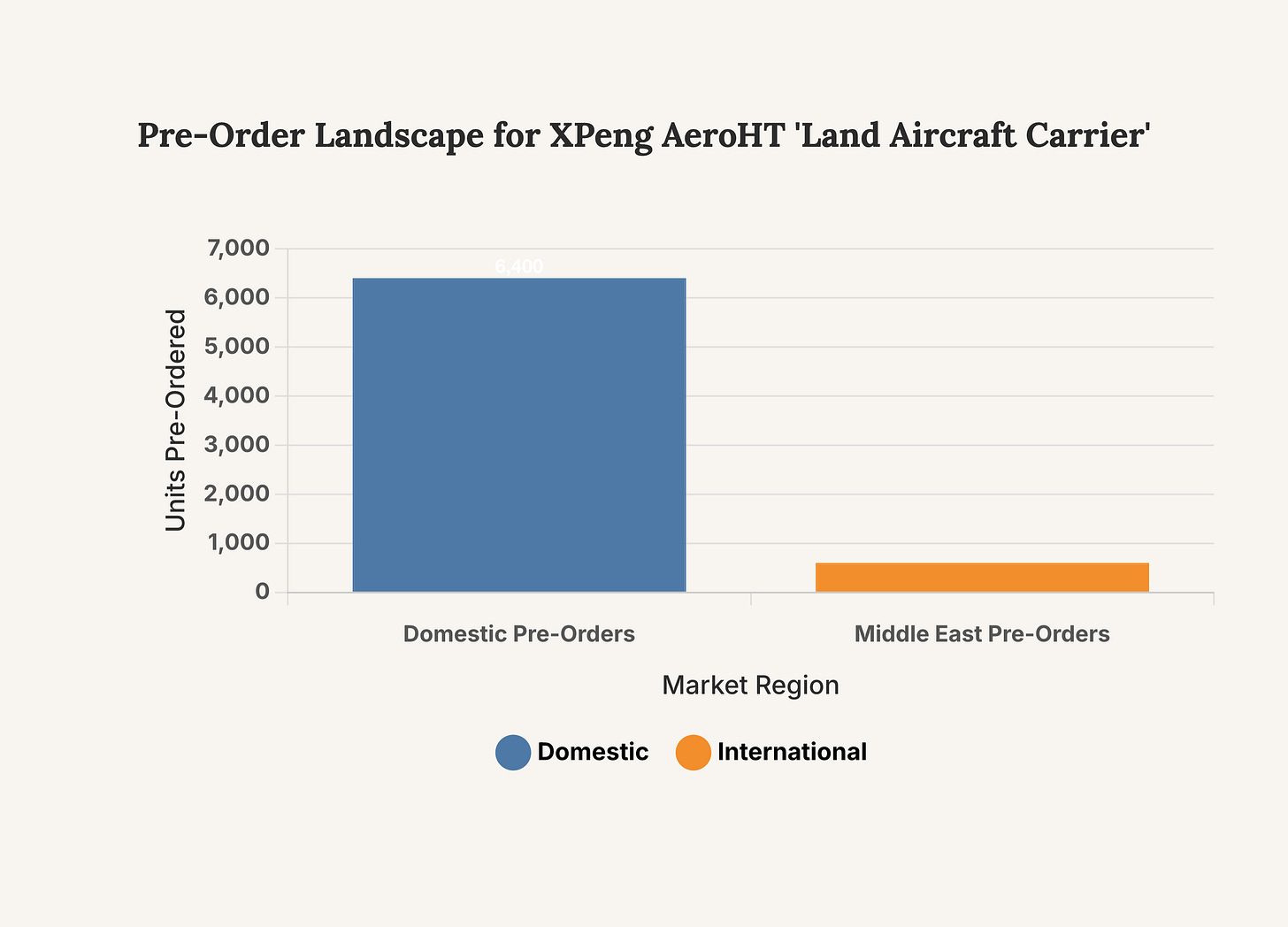

The Automotive Invasion: XPeng and Geely’s Roadable Revolution

Leveraging China’s world-leading EV supply chain, automotive giants are storming the sector. XPeng AeroHT (recently rebranded Aridge) is pursuing a novel modular concept with its “Land Aircraft Carrier.” This is a six-wheeled electric van that carries a detachable two-person eVTOL in its rear, allowing for seamless ground-to-air travel. The company has already begun trial production at a massive new factory in Guangzhou with a planned annual capacity of 10,000 units, has secured over 7,000 pre-orders, and is targeting mass production and deliveries in 2026.

“The ‘low-altitude economy’ is one of the few business models created by China, which represents an opportunity for us to take a leadership role.”

- Yang Jun, Director of Shensi Lab

Similarly, Geely’s subsidiary, Aerofugia, is developing the AE200, a larger, five-to-six-seat piloted eVTOL designed for longer intercity routes. Having completed crucial test flights and entered prototype production, Aerofugia represents a more conventional approach aimed at creating a true air taxi service, directly competing with Western designs from companies like Joby and Archer.

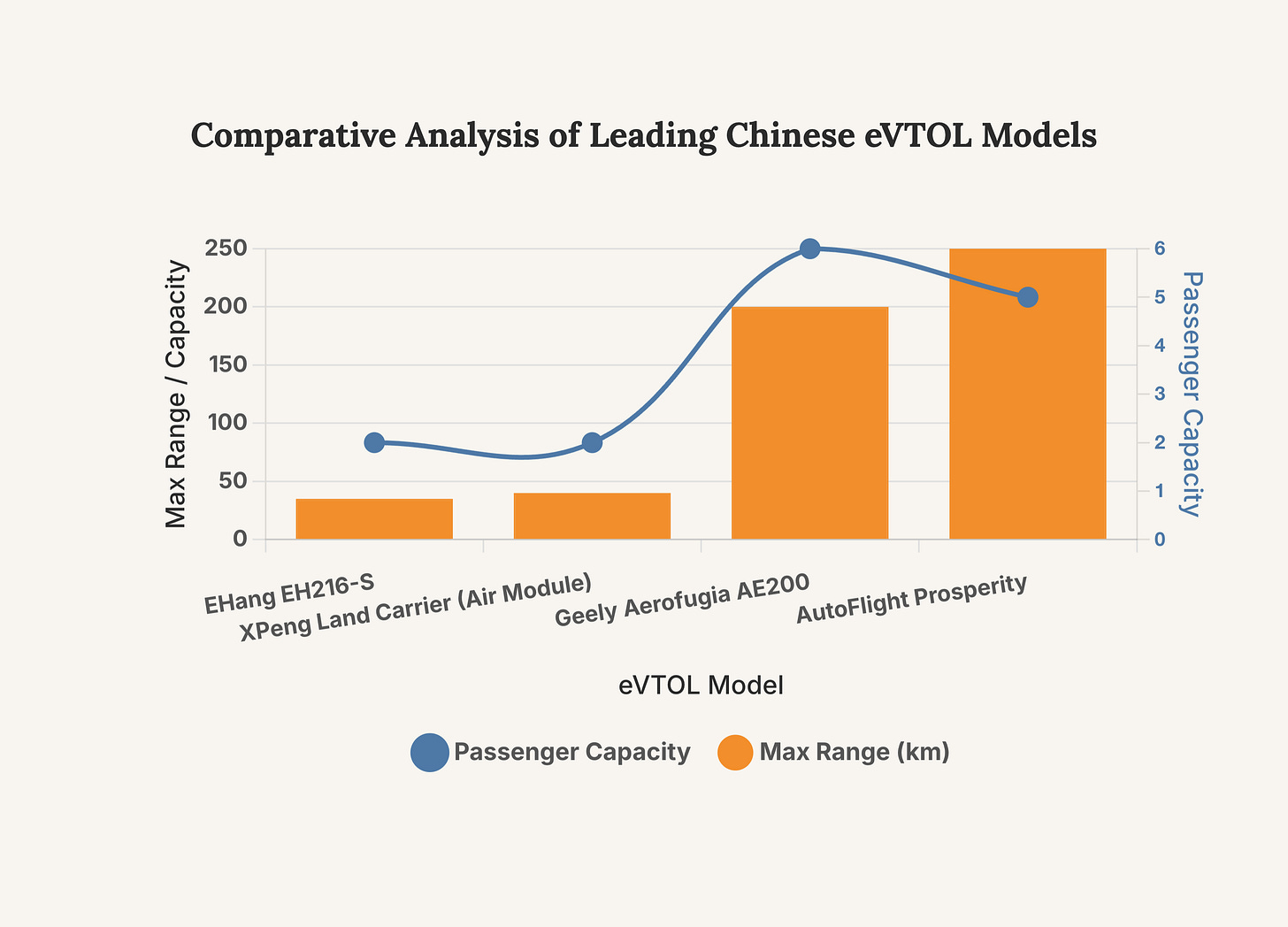

This chart highlights the diverse strategies of China’s top eVTOL players. EHang and XPeng are targeting short-range, low-capacity autonomous and modular applications, while Geely and AutoFlight are developing larger, piloted aircraft for intercity travel, indicating a multi-faceted approach to capturing the entire market spectrum.

The Logistics Backbone: AutoFlight’s Cargo Dominance

Before passengers fill the skies, cargo will pave the way. AutoFlight has strategically focused on this segment, achieving a world-first by securing full CAAC certification for its CarryAll, a ton-level cargo drone. This provides a crucial pathway to revenue and operational scale while the passenger market matures. AutoFlight is using the data and experience from its cargo operations to inform the certification of its five-seat passenger aircraft, the Prosperity, demonstrating a pragmatic, phased approach to market entry.

Forging the Ecosystem: Beyond the Vehicle

A flying car is useless without the infrastructure to support it. Recognizing this, China’s strategy extends far beyond aircraft manufacturing. The government is actively orchestrating the build-out of a comprehensive low-altitude ecosystem, addressing everything from landing sites to air traffic control.

Vertiports and Digital Skies

The national plan includes the construction of a grid of hundreds, and eventually thousands, of vertiports (take-off and landing stations) across the country. The southern Guangdong region alone is planning a network of over 600 stations. More critically, China is developing a national, unified digital air traffic management system for low-altitude airspace. This is a monumental undertaking that leverages the country’s strengths in 5G and AI to create a smart, responsive network capable of safely managing tens of thousands of simultaneous flights—a prerequisite for any mass-scale urban air mobility (UAM) operation.

Initial Use Cases: From Tourism to Emergency Response

Commercial rollout is being pursued through a carefully phased strategy. The initial applications are not widespread commuting but are focused on controlled, high-value scenarios. Aerial sightseeing, as demonstrated by EHang, provides a low-risk environment to build public confidence and generate early revenue. Other key initial markets include emergency medical services, logistics, and connecting remote areas, which offer clear societal benefits and justify the high initial costs. For example, AutoFlight recently demonstrated a flight to an offshore oil platform that cut a 10-hour boat journey down to just one hour. These targeted applications serve as real-world laboratories, paving the way for eventual mass transit.

This chart shows the significant early demand for XPeng AeroHT’s modular flying car. While the domestic market forms the bedrock of its order book, the substantial pre-order from the Middle East signals a clear international appetite for China’s technology and a potential export-led growth strategy.

Strategic Outlook: Headwinds and Trajectory

Despite the undeniable momentum, China’s path to low-altitude supremacy is not without challenges. Technological dependencies on certain foreign high-performance chips and sensors remain a vulnerability. Furthermore, the CAAC’s rapid certification process, while a domestic advantage, is viewed with caution by Western regulators, potentially creating a fragmented global market with divergent safety standards and limiting the international expansion of Chinese firms. The sheer capital investment required for infrastructure and the long-term question of economic viability for consumers also present significant hurdles.

However, the strategic alignment of government policy, industrial might, and technological innovation gives China a formidable and likely insurmountable lead. While the West debates, China builds. While others certify, China flies. The nation is not just participating in the flying car race; it is building the entire racetrack, writing the rulebook, and training the first generation of champions.

The second-order effects will be profound. Dominance in the low-altitude economy will grant China significant influence over global standards for the next generation of mobility. It will create a powerful new export category and deepen technological dependencies for nations that adopt its ecosystem. For investors, industry leaders, and policymakers, the key signpost to watch is not the success of a single vehicle, but the pace at which China integrates its national digital sky network. Once that is fully operational, the barrier to entry for foreign competitors will become nearly absolute.

China is methodically constructing a closed-loop ecosystem for the low-altitude economy, leveraging a protected domestic market to scale and perfect a model it intends to export globally.