After a 43-Day Data Blackout, Inflation Reappears at 2.7%

The first post-shutdown report reveals a surprising energy surge hidden beneath the cooling headline numbers

For forty-three days, the dashboard of the American economy went dark. Following the federal government shutdown that began in October, the Bureau of Labor Statistics suspended its data collection, leaving policymakers and investors navigating the most complex economic turn of the decade without a map. Yesterday, the lights flickered back on.

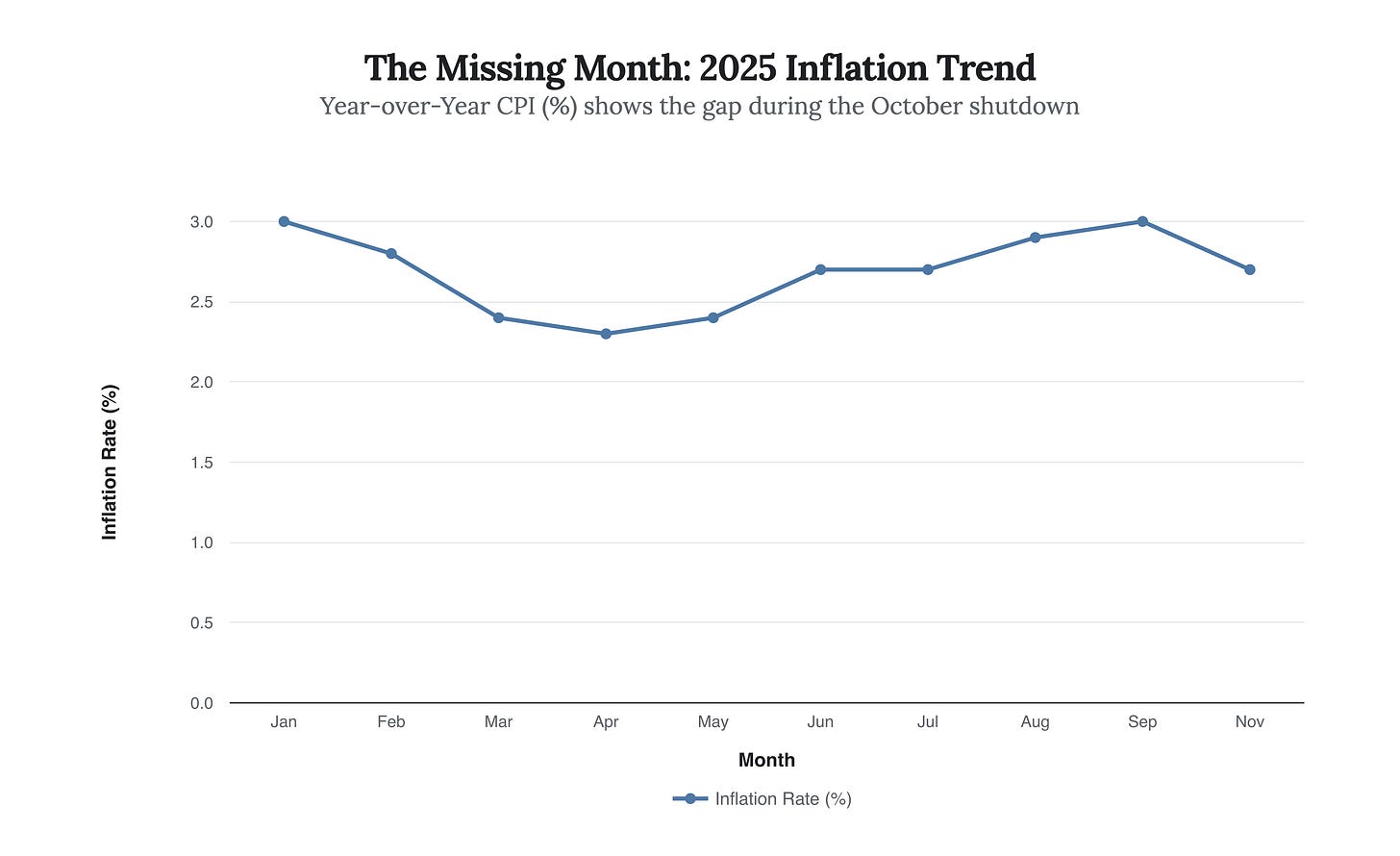

The data released Thursday morning offers the first clear glimpse of the landscape since September, and the topography has shifted. The headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) for November arrived at 2.7% year-over-year, a welcome deceleration from September’s 3.0% pace and the lowest reading since July. On the surface, it is a victory—a sign that the inflationary fever is breaking. But beneath the calm aggregate number lies a more volatile reality: while the overall temperature is dropping, specific sectors are heating up with renewed intensity.

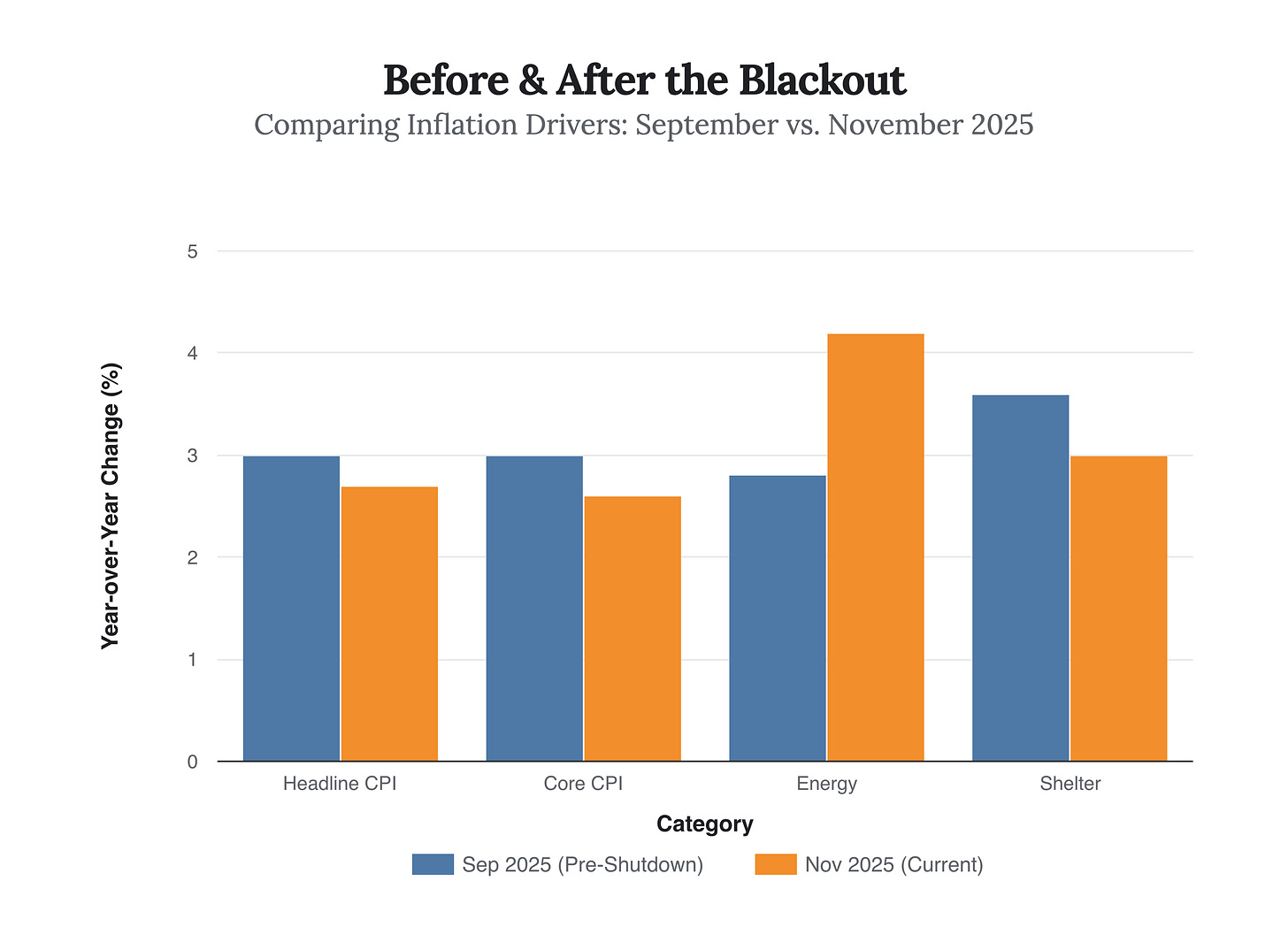

The most striking divergence is in energy. During the data blackout, while service inflation cooled, energy prices quietly surged. This decoupling suggests that while the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy is effectively dampening core demand, it remains powerless against the supply-side shocks rattling the energy markets.

The visual gap in the chart above is not a glitch; it is the scar of the 43-day shutdown. The absence of October data creates a discontinuity that statisticians will struggle with for years, but the trend line connecting September to November tells a story of relief. After climbing steadily through the late summer to reach 3.0% in September, the inflation rate has snapped back down.

However, the composition of this 2.7% figure is radically different from what we saw earlier in 2025. The “Core” CPI, which strips out volatile food and energy, has dropped significantly to 2.6%, its lowest level since early 2021. This indicates that the sticky service-sector inflation—the “last mile” problem that has plagued the Fed—is finally loosening. Shelter costs, long the stubborn anchor of high inflation, decelerated to 3.0% from 3.6% in September.

Yet, as the core cools, the volatile edges are fraying. Energy costs did not get the memo. Driven by a spike in fuel oil and natural gas, the energy index accelerated sharply, creating a tug-of-war within the data.

The chart above reveals the internal rotation of the economy during the data blind spot. The green bars (November) are lower than the blue bars (September) for Headline, Core, and Shelter. But look at Energy: it jumped from 2.8% to 4.2%. This 140-basis-point swing in a single sector acted as a floor, preventing the overall inflation rate from falling even further.

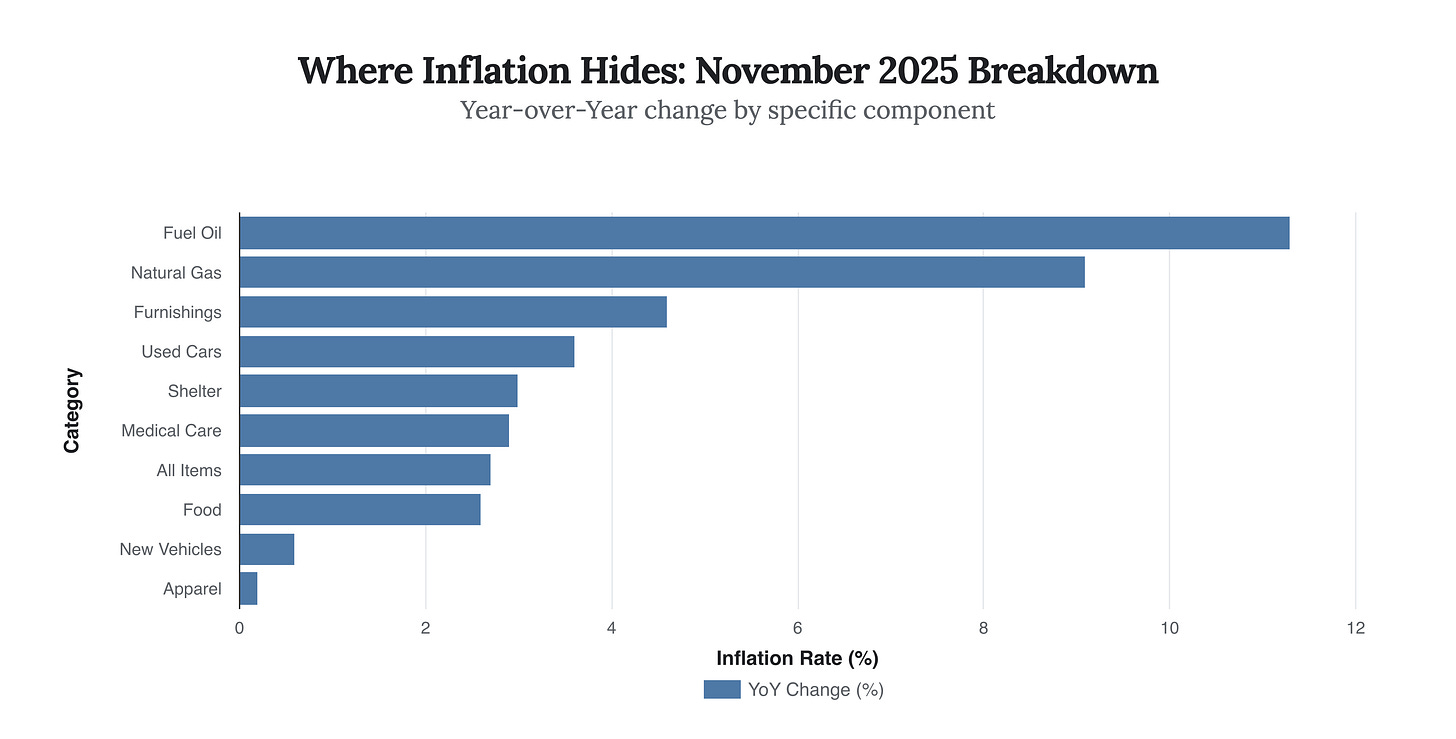

“The decline in used car prices has ended, with prices up 3.6 percent... [and] fuel oil soaring 11.3 percent.”

This resurgence in goods and energy prices is particularly concerning for lower-income households, for whom these items constitute a larger share of the monthly budget. While the “Davos economy” of services and rents is cooling, the “kitchen table economy” of heating oil and used cars is heating up.

Fuel oil alone surged 11.3% year-over-year, and natural gas followed with a 9.1% rise. These are non-negotiable expenses as we head into the winter months.

The detailed breakdown exposes the uneven nature of this recovery. While apparel prices are barely moving (0.2%), the cost of keeping a home warm (Fuel Oil, Natural Gas) and furnished (Household Furnishings, +4.6%) is rising at multiples of the headline rate. This divergence complicates the Federal Reserve’s path forward. The cooling of the labor-intensive service sector suggests their policies are working, but the flare-up in commodity-driven sectors implies that external supply constraints are still in play.

As we close 2025, the data suggests we have entered a new phase of the economic cycle: one of asymmetric disinflation. The broad, synchronized price increases of 2022-2024 are over. In their place is a fragmented landscape where stability in one sector (rents) masks volatility in another (energy). The lights are back on at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but the picture they reveal is far from uniform.